Bernbach to the future

A principle isn't a principle until it costs you money, said Bill Bernbach. In the wake of the 2022 purpose vibe shift, it's useful to look back at when and why he said it.

For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Happy new year to all readers. The more attentive among you may remember I began last year by declaring that “dismantling the meme of Purpose is essential to building a happier and more functional society”. This year, I’m happy to report some progress on the Great Dismantling—to the point where I’m hoping to broaden out from purpose in the year ahead. But first, I want to look back briefly at 2022, before looking back even further to the career of a great ad writer: Bill Bernbach.

1. The purpose vibe shift

The various reviews of last year agree there has been a change of mood in the purpose debate, captured in some high-profile interventions. Investor Terry Smith tore into Unilever’s management for their uni-dimensional focus on purpose. Procter & Gamble’s Mark Pritchard talked about the industry going ‘too far into the good’ (crazy that purpose ends up with people having to talk this way) and needing to refocus on growth. Even Patagonia’s heavily spun ‘going purpose’ move contained a death blow to the corporate purpose movement, with Yvon Chouinard stating that public companies can never make it work, however good their intentions.

Mark Ritson recounts these events in the purpose section of his Top 10 Marketing Moments of the year. I’m tempted to say I enjoyed his take so much that I wrote it myself in 2017. My first piece on purpose for Creative Review (optimistically titled ‘Is this the end for brand purpose?’) ended like this:

Five and a half years later, we may finally have reached that tipping point.

I have some issues with the way Mark Ritson frames his version of the case, not least his take on the Patagonia story, which I wrote about here. But for now, I want to talk about the man we’re both quoting: Bill Bernbach.

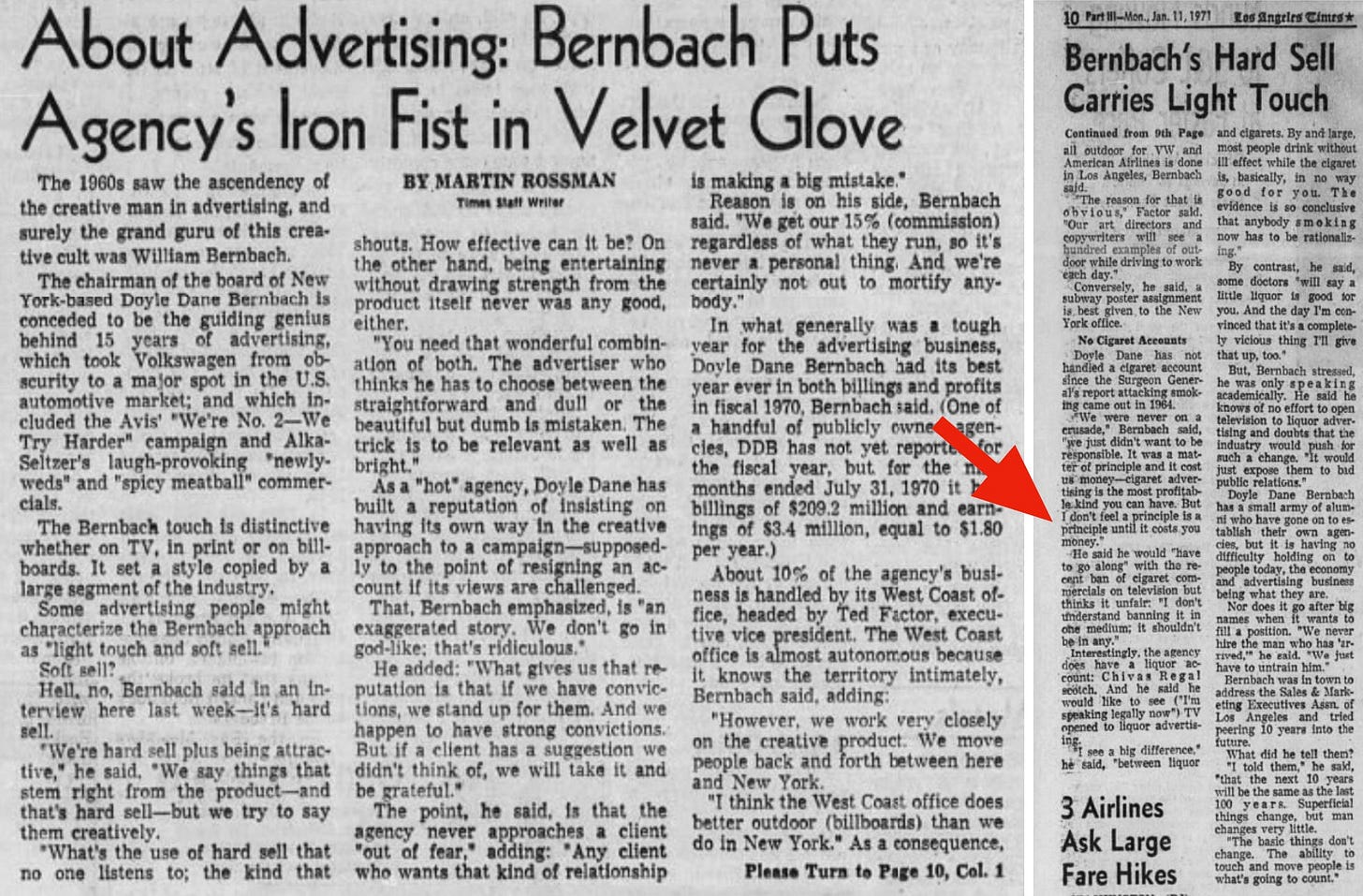

Looking at his quote again, I started to wonder why an adman was talking about ethics in the first place. Initially, I traced the quote to a book called Bill Bernbach Said… —a collection of aphorisms published by DDB in 1989. But it left me wondering about the original context. Eventually, I found it in a Los Angeles Times interview from January 1971. On behalf of curious Thoughts on Writing readers, I have retrieved the archived original and shared it above (links here and here).

2. Cigarets and alcohol

It turns out Bernbach was talking about cigaret advertising (strange how they spelt it back then)—and his agency’s decision to turn away all cigaret-related work. As the article explains: Doyle Dane [Bernbach] has not handled a cigaret account since the Surgeon General’s report attacking smoking came out in 1964.

At this point, you might be thinking: good for Bill Bernbach, purposeful before his time, doing the full Yvon Chouinard, firmly on the right side of history, let’s give him a posthumous start-with-why award.

Bernbach himself strikes a more modest tone: “We were never on a crusade… we just didn’t want to be responsible. It was a matter of principle and it cost us money—cigaret advertising is the most profitable kind you can have.” And then the fabled quote: “But I don’t feel a principle is a principle until it costs you money.”

It’s a powerful turn of phrase—the kind of thing you might expect from a great adman who is making a persuasive case for his agency in the pages of the LA Times, where potential clients will be reading with interest.

But note the immediate disclaimer: “We were never on a crusade”. Bernbach’s instinct is not to set himself up as a moral hero. And the caution is warranted.

In truth, the sacrifice involved in cases like these is always complex. Ad agencies are set up to handle a finite amount of work, so the act of turning away work is not necessarily a real-terms loss, especially for agencies who are in high demand. In pure ethical terms, there is also a distinction between an actual cost, in the sense of losing money you have now, and a theoretical cost, in the sense of foregoing potential future income over and above what you will continue to make. Both costs matter, but only one leaves you going home poorer, maybe to a smaller house.

In terms of strict business calculation, you can also see it as a case of enlightened self-interest. The Surgeon General’s report has already made clear which way the wind is blowing, so any agency reliant on tobacco advertising is perilously exposed. Much better to get out in front of the inevitable and turn it into a positive PR story—the kind of thing that gets the interest of LA Times journalists, and which might lead to more lucrative, long-term work from elsewhere.

None of which is to succumb to cynicism, but simply to weigh the ethical and practical considerations honestly. I’ve been in this position of turning away work for ethical reasons. It gives me a warm feeling that I like to think isn’t totally unwarranted, but if I’m really introspective about the thought process, I know there are many cost-benefit calculations bouncing around in my head, because that’s what life is like. And it’s even more complex when you’re responsible for employees with rents to pay and ethical opinions of their own.

Ultimately, I respect Bernbach for taking the stance he did, but mostly I respect the way he didn’t make too big a deal about it—there’s no sense of pompously shaming the agencies who do otherwise. And I’ll come back to an important coda to this story near the end of this post.

For now, notice where the LA Times interview goes next—from cigarets to hard liquor. Bernbach recognises the ethical tensions with holding the Chivas Regal account, though he makes a valid distinction between cigarets being “basically in no way good for you”, while most people drink whisky without ill effect. He’s speaking at a strange time in advertising history when liquor/spirits advertising never appeared on television and radio—not because it was outright banned, but because liquor companies voluntarily chose to ban themselves from these supposedly powerful media. Fearing the return of Prohibition if America developed too big a drinking problem, liquor companies decided it was better to stay under the radar and play the long game. It was only in the 1990s that things changed—by which time, cigaret advertising was already exiting stage left.

I mention the liquor story as a historical aside—to show how the ethical debates around different sectors evolve. From a distance of 50 years, it’s interesting to see Bernbach wrestling with these issues in a grown-up way, without the moral grandstanding of a purpose-inebriated James Watt (for example).

3. The right-ish side of history

Bernbach has a complex legacy when it comes to purpose. As you would expect of a great adman, he was clear-eyed about the nature of the job: “The purpose of advertising is to sell. That is what the client is paying for and if that goal does not permeate every idea you get, every word you write, every picture you take, you are a phony and you ought to get out of the business.”

Not much comfort for purpose advocates there. But the cigaret story was one of two high-profile cases of Bernbach making ethical calls about exactly what his agency was prepared to sell.

The other came in 1964 when Doyle Dane Bernbach engaged in its one and only campaign for a political party. Faced with the unsavoury prospect of Barry Goldwater winning the election for the Republicans, the agency accepted an invitation to work on incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign. The result was one of the most remembered political ads of all time: Daisy.

The ad only ever ran once, at a time when the public mood was already swinging decisively in Johnson’s favour, so it would be excessive to say it ‘won’ the election. But it generated huge press coverage and cemented the idea that Goldwater represented an existential threat, without ever mentioning him by name. The Republicans were outraged, seeing it as sensationalist and manipulative. But, among a series of other ads, it did its job and the Democrats won comfortably. Purposeful mission accomplished, you might say.

But, while the ad may not have decisively influenced the result, it certainly influenced all political advertising thereafter, and not necessarily for the better. One of Bernbach’s unsought legacies is to be hailed as the godfather of ‘negative’ political advertising—the kind that bypasses rational argument and appeals to primal emotions. Political historians have drawn a straight line from Daisy to Reagan’s 1984 Morning in America and George W Bush’s 2004 Wolves.

The approach reflected Bernbach’s belief that persuasion is an art more than a science. One of his other famous quotes follows the familiar ‘x isn’t x until y’ formula:

“The truth isn’t the truth until people believe you and they can’t believe you if they don’t know what you’re saying; and they can’t know what you’re saying if they don’t listen to you; and they won’t listen to you if you’re not interesting. And you won’t be interesting unless you say things freshly, originally, imaginatively.”

I get the spirit of what he’s saying—that you’ll never convince people of anything unless you get their interest first. But it’s easy to slide from “The truth isn’t the truth until people believe you” into a postmodern, relativist, quasi-Trumpian “If enough people believe it, it’s the truth”. I’d prefer to work from the idea that some truths are true no matter who believes them.

4. A bittersweet coda

There’s one more twist in the Bernbach tale.

Less than three months after his death in 1982, his agency ended the ban on tobacco advertising and took on the Parliament cigarette account—a small account in itself, but a foot in the door of the world’s fourth biggest advertiser at the time, Philip Morris. The story was significant enough to be reported in the New York Times.

As the article notes, a similar fate befell David Ogilvy, another great copywriter and the first agency chief to ban tobacco advertising based on personal conviction—a ban subsequently lifted by new management.

Both stories can be seen as a depressing reflection on the industry. But there is a more inspiring moral at their heart. As the New York Times article notes, Bernbach fully accepted the transfer of power when he stepped down as Chief Executive in 1976, remaining in an honorary Chairman role. His words at the time: “Look, you people are running the company now—you’re going to have to make up your own minds.”

As it happened, the new owners made up their minds to follow the money—although they chose to retain a ban on political advertising, which Doyle Dane Bernbach put in place following the 1964 campaign, perhaps realising the Pandora’s box they had opened.

5. Purpose is personal

For me, Bernbach’s words point to something significant. He was a man with ethical convictions, but he also had the humility to recognise the distinction between himself and the company. It’s a distinction that gets blurred in today’s age of purportedly purposeful businesses.

In my recent post on Paul Newman and Patagonia, I ended by saying: Above all, we should rediscover the true locus of purpose: not in boardrooms, PowerPoint presentations or supermarket aisles, but in living rooms, pub conversations, community organisations and voting booths.

A shorter version of the same thought could be this: Purpose exists in people, not companies.

Purpose is personal. That’s how it always was, before corporations and marketers latched onto it as a way to blur important, and inconvenient, distinctions—like those between citizen and consumer/employee, for-profit and not-for-profit, public realm and private sector.

If purpose is finally spiralling down the drain of its own contradictions, then this is the baby that needs to be reclaimed from the bathwater. In the realm of business, the best way to conceive of purpose is as a human imperative that acts as a counterbalance to the natural momentum of corporations. The ethical calls aren’t always easy or clear-cut and certainly not always a win-win. The snake oil of the purpose movement was always to pretend that purpose was the internal driver of corporate success, rather than an external check on its natural excess. The results have caused havoc over the past decade and are one reason we live in a plutocracy of holier-and-richer-than-thou corporate monopolies and clownish tech bro billionaires.

6. Bernbach to the future

The point of this extended Bernbach archaeology is to look back in order to look forward.

While there has been a welcome purpose vibe shift, there is still a reluctance to follow the train of thought all the way to the end. Mark Ritson gets close when he says that “The purpose of purpose is purpose”. It ought to be self-evident that the point of doing good is to do good, not to drive sales. But if that is the case, then that is how purpose campaigns should be evaluated—by marketing columnists as well as by advertising awards.

The next time any commentator celebrates Dove, Cadbury’s or Ben & Jerry’s for their purposeful approaches, let them remember that The purpose of purpose is purpose. So the praise should be based on a rigorous assessment of the social good these businesses claim to deliver. The commercial results are irrelevant and borderline tasteless to discuss in the context of purpose. This will necessarily take you outside the realm of marketing effectiveness, just as the companies you’re assessing are straying well beyond the realm of their expertise. But the purpose of purpose is purpose, and this is the shift it requires.

Or you can take the train of thought all the way to the final stop, which is to realise that purpose, even in a more moderate, ‘common sense’ form, does not map onto for-profit businesses and their for-profit marketing campaigns. And that is fine—we have always had these distinctions for a reason, and society as a whole functions better when we recognise them. That is the common sense we need to rediscover. Yes, celebrate Dove or Cadbury’s for effective marketing campaigns if the figures add up, but don’t pretend it has anything to do with purpose—because you’re contradicting the maxim you used to define purpose in the first place: The purpose of purpose is purpose.

As I’ve said before, this need not leave us in an amoral, profiteering hellscape. But it leaves us closer to the position of a Bill Bernbach turning away the tobacco work—a decent human being doing his best to navigate the imperfect world of business with his conscience reasonably intact and with appropriate humility about the limits of his powers.

One of Bernbach’s great VW ads later provided the title of a biography by Doris Willens. She writes that Bernbach used to tell clients “Nobody’s perfect and no one’s going to believe you if you claim to be.” In a world of hubristic brands high on their purposes, it might be the best quote to remember him by.

Thanks for reading. It may entertain some readers to learn I’m the Jury President for Writing for Design at D&AD this year, and I’ll be one of three speakers at D&AD on 26 January—please come along if you’re in the area.

Best piece on marketing I’ve read in a long time. I’ll let you tell us how long. 😀

'I’m tempted to say I enjoyed his take so much that I wrote it myself in 2017.' 🔥🔥🔥