Patagonia, Paul Newman and another kind of purpose

In 'going purpose', Patagonia may have killed the thing it loves. Now, rather than relying on conflicted billionaires, we should embrace the humour and humility of Paul Newman.

For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Regular readers will know I have a problem with purpose. I’ve been thinking about it since at least 2017, when I wrote an article for Creative Review titled ‘Is this the end for brand purpose?’—proof of the journalistic rule that the answer to any question posed in a headline must always be ‘No!’

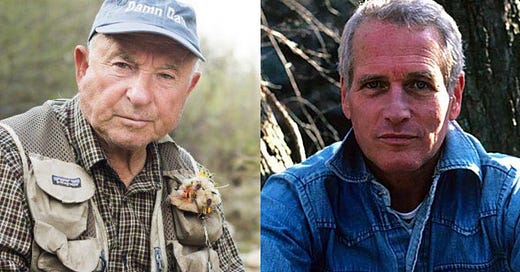

Recent events have hinted at a new answer: yes. And it’s a strange irony that the slayer of the purpose dragon is now being hailed as its saviour. In this post, I want to talk first about Yvon Chouinard and his unresolved purpose issues. Then I want to go super-positive and share one of the most inspirational stories in business, involving Paul Newman and his salad dressing.

1. The strange death of purpose

Yvon Chouinard is the unlikely dragon slayer. And the chalk outline of the dragon can be found mainly in these two paragraphs, taken from his recent open letter.

The second paragraph is more ruthlessly uncompromising than anything I’ve ever written about purpose. Public companies, even those with good intentions, cannot be purpose-driven!

Seriously, it’s worth re-reading and imagining the agonised cries from various corners of the purpose industrial complex: “Even public companies [‘Aargh!’—Unilever] with good intentions [‘Mon dieu!’—Danone] are under too much pressure [‘Hey!’—BlackRock] to create short-term gain [‘Oof!’—US Business Roundtable] at the expense of long-term vitality [‘Et tu?’—Ben & Jerry] and responsibility [‘Why?’—Simon Sinek].”

For years, these people have been insisting that the circle of shareholder obligations can be squared by a sufficiently passionate belief in purpose. Can any of these companies seriously claim to be purpose-driven from this day forward? If they do, will anyone point out that Yvon Chouinard, the patron saint of purpose, emphatically disagrees with them?

More subtly, the first paragraph of that Chouinard quote gets to heart of the business purpose fallacy. If a privately held corporation can be imbued with purpose, why be so afraid of someone new at the helm? There can be no company on the planet with a deeper claim to ‘purpose’ than Patagonia. Since day one, its values have been encoded in its DNA and woven into every aspect of its evolution. Yet, half a century later, its founder still cannot trust a new owner to carry on the momentum.

That’s a fair instinct, but it says something profound, and profoundly obvious, about purpose. There is no such thing as business purpose. There is no such thing as brand purpose. There is only human purpose. Yvon Chouinard and his family rightly recognise there is no reliable way to encode purpose in their business in a way that can live independently of them. The Patagonia story has been reported as a new model for businesses to follow, but in truth it’s a story about the failure to find any model that can exist beyond the tight control of a family-held trust. Rather than a story about purposeful business, it’s a story about billionaire philanthropy: and one with an under-reported political dimension.

2. The conflicted hero

Before I go on, I should say I like Yvon Chouinard. I love how he was a misfit in school, as so many successful people were. And I admire how he’s wrestled with these questions with more honesty than most people can muster. In many ways, he is the perfect patron saint of purpose, because he is aware of being a walking contradiction: a billionaire businessman who hates being called either a billionaire or a businessman. By his own account, he is a failure: an environmental activist whose business is inseparably tied up with consumerism, growth and a carbon footprint that he can only ever reduce, not eliminate.

But that honest activism has always been in conflict with a self-publicising instinct: a tendency towards grand branding gestures that see the internal contradictions writ large.

As a piece of advertising history, this ad from 2011 is hard to beat. It was heralded as a business finally doing the right thing and telling people to consume less. But anyone with the most basic marketing instinct knows that a full-page ad in the New York Times on Black Friday, complete with logo and product shot, and surrounded by a halo of altruism and good vibes, is going to do what ads tend to do. Patagonia’s sales reportedly rose 30% in the nine months following the ad—philosophy students can discuss whether it therefore ‘worked’.

The same tendency towards self-celebration was evident in the PR around the new business structure. Earth is now our only shareholder said the headline. Instead of “going public,” you could say we’re “going purpose” said the press release. It’s a snappy line, but a strange one for someone so clearly aware of the delusions in the wider purpose movement. You would think Yvon Chouinard might not want to fan the flames of that particular fire, but many CMOs on LinkedIn have taken it as a sign that their dragon is alive and well. Like much of what Patagonia does, you could describe it as good PR, but bad activism. They could have come out and said that Purpose is a self-serving delusion and we want no part of a movement that sets back the cause of real environmental action. But it would be less popular among people who buy high-performance fleeces for the arduous walk from the front door to the Tesla.

3. Holdfast and break things

Now let’s get to the details of the new structure, because they are relatively novel. Patagonia is transferring 100% of its voting stock to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, created to uphold the values of the company, while all of its nonvoting stock will go to the Holdfast Collective, a nonprofit “dedicated to fighting the environmental crisis and defending nature”. Each year, Patagonia will keep enough profits to cover its operating costs, while handing the rest over to the Holdfast Collective, which will use the money “to fight the environmental crisis, protect nature and biodiversity, and support thriving communities”. Importantly, the Holdfast Collective is recognised as tax-exempt under the US Internal Revenue code 501(c)(4)—which means that, unlike public charities, it is legally allowed to engage in political activity.

As commentators have noted, there is a recent parallel for this move. Only a few weeks ago, the New York Times reported on Barre Seid, the right-wing billionaire who handed his company over to a conservative nonprofit organisation, which immediately sold it to generate $1.6 billion to spend on conservative causes—including fighting action on climate change. The move was reported as an example of ‘dark money’ influencing politics: a billionaire converting his market power into long-term political influence. Patagonia can reasonably claim to be less dark—there is no mystery about where the money is coming from, although there will be limited transparency on where it’s going. But it’s undeniably part of the same trend for private interests muscling into the political process. Carl Rhodes, a notable left-wing critic of purpose, has examined why this is worth worrying about, concluding:

We live in an era in which business owners are taking over as society’s moral arbiters, using their wealth to address what they see as society’s greatest problems. Meanwhile, the wealth and number of the world’s billionaires grows, and inequality stretches society to breaking point.

It is great that Chouinard is putting his company to work for the future of the planet. What is not great is how our lives and our futures are increasingly dependent on the power and generosity of the rich elite, rather than ruled by the common will of the people.

I agree—we can cheer on the billionaires on our own side of the political divide, and we can take the grimly realist view that fire has to be fought with fire. But a better strategy, both short and long-term, would be to choose our heroes more wisely. And we could do worse than choose Paul Newman.

4. Another kind of purpose

Newman’s Own is one of the most inspirational stories in branding—I nodded towards it at the end of my appearance on the Call To Action podcast.

It began in 1982, when actor Paul Newman converted his long-standing obsession with salad dressing into an unexpectedly successful business venture. This wasn’t the usual celebrity endorsement of someone else’s product. Newman had spent years asking restaurant waiters to bring the raw ingredients to his table so he could mix up his own dressing. He began mixing vats of the stuff in his basement, with a vague plan to sell a few bottles in his local area. Alongside his partner, the writer A.E. Hotchner (former travelling companion and biographer of Ernest Hemingway), Newman became closely involved in the challenges of production, bottling and distribution—all the while insisting on using natural ingredients in an industry that had become reliant on chemical preservatives.

Among other things, the story was an early example of packaging being used as the main marketing platform. Paul Newman was reluctantly persuaded to include his name and face on the label—it was the only chance they had of getting noticed. But he could only live with the idea if he wasn’t seen to be profiting from it—it all seemed a bit crass otherwise, and he didn’t expect to make much money in any case. “Let’s give it all away,” he announced. From that day forward, Newman’s Own gave all its profits to charity, starting each new year at zero.

It turned out there was a lot of profit—from salad dressings, pasta sauces, pizzas, coffee and many other things. Newman set up an unusual structure to handle the unexpected success: Newman’s Own shifted as much product as possible, while the legally separate Newman’s Own Foundation made the decisions about where to invest the proceeds. Most notably, the foundation set up a network of purpose-built outdoor camps for terminally ill children: giving them the chance of a joyful experience with children in a similar predicament, while surrounded by trained carers and access to advanced medical facilities. The idea became a phenomenon that spread around the world.

There is no more inspirational tale of purpose in business—except that purpose is the exact wrong way to frame it. “I really cannot lay claim to some terribly philanthropic instinct in my base nature,” said Paul Newman of the venture. “It was just a combination of circumstances. If the business had stayed small and had just been in three local stores, it would never have gone charitable. It was an abhorrence of combining tackiness, exploitation, and putting money in my pocket, which was excessive in every direction.” Describing the subsequent idea for the camps, Newman says: “I’d be pleased if I could announce a motive of lofty purpose. I’ve been accused of compassion, of altruism, of devotion to Christian, Hebrew, and Moslem ethic, but however desperate I am to claim ownership of a high ideal, I cannot.”

Like most successful entrepreneurs, Newman didn’t start with why, but with an obsessive focus on the what. Under pressure to cut corners in production, Newman and Hotchner held their ground and researched ways to make the product both natural and commercially viable. Early buyers from the big chains paid tribute to this single-minded product focus: “The dressing’s success rests not in Mr. Newman’s name or the company’s nonprofit status, but in the taste. It’s different from other salad dressings and it’s high quality. People buy it for the same reason they buy other products. They like it.”

Three other things I love about the story:

It’s further disproof of the idea that creative packaging copy started with Innocent in 1999. Every Newman’s Own product contained a whimsical cock-and-bull story about its origins. And early bottles of salad dressing were decorated with comically grandiose Latin mottos and the excellent line “Fine Foods Since February”.

Not unrelated to the first point, the co-founder was a writer, which confirms my self-serving idea that narrative is an under-appreciated part of business success. Founders don’t need a purpose, but it helps to have a gift for story-telling—an instinct for creating a lore around the brand as you go along.

Not unrelated to the first and second point, humour was a big part of the story: partly as a way of generating funny PR and packaging copy, but also as a way of thinking about business, and about life. There was a lightness of touch that is entirely absent from the po-faced businesses of today. You would never catch Paul Newman doing what Yvon Chouinard is filmed doing on the Patagonia site: handwriting ‘Earth is now our only shareholder’ before gazing meaningfully out of the window. Newman had too keen a sense of irony for that, even though he had more claim than anyone to doing direct, hands-on work for good.

The whole story is related in an excellent book titled Shameless Exploitation in Pursuit of the Common Good—Newman’s ironic phrase that captured the two sides of the operation. Originally published in 2003, the book was re-released in 2008 with the toned-down title: In Pursuit of the Common Good—an unfortunate act of editing that loses the essential humour of the brand. Paul Newman died in the same year, but Newman’s Own remains a remarkable outlier in the field of business and philanthropy. In 2018, its unusual structure led to the Newman’s Own Exception being written into law by Congress: a narrow exception created after some unease about whether this unusual alliance of for-profit and nonprofit organisations might be used as a way around corporate tax law.

5. A very practical joke

In the recent Patagonia coverage, some commentators have noted the parallel with Newman’s Own, which got there four decades earlier. But there is a crucial difference.

The Newman’s Own structure contains a clear separation of church and state, or more accurately of corporation and state. The charitable side is a separate entity run by sector experts who know what they are doing, while the business side is run by product and marketing people who know what they are doing. There is no pretence that every marketing campaign is somehow a campaign for good—Paul Newman reluctantly recognised the need to tell customers that 100% of profits went to charity, but he was instinctively against what he called “noisy philanthropy”. In the same way that using his own image for profit felt tacky, the idea of leveraging the good cause as a marketing tool felt equally tacky. He never lost sight of the founding logic: he was doing this because he had an intense interest in salad dressing. The philanthropy was an unexpected by-product. As he describes it, the venture began as a joke, but turned into “a very practical joke”.

This is more than a difference in attitude: it’s a difference in legal status. The Newman’s Own Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organisation whose tax-exempt status requires it not to fund political candidates or lobby for legislative change. Patagonia is pointedly different: it is explicitly set up to intervene in the democratic process. And it’s this blurring of church and state that has always struck me as the heart of the problem. However favourably you look on individual cases, it’s a disturbing pattern to endorse and reinforce.

Wherever you sit on the political spectrum, whatever your stance on degrowth versus decoupling, whatever your view on the other social issues that might be salient in any given state election, your choice of fleece will help steer political outcomes in ways beyond your control. Some people might call this ‘consumer activism’, but it’s the kind where you do the consuming and a single powerful family does the activism. And however you dress it up, it all revolves around continuing consumption and economic growth, as Yvon Chouinard himself has ruefully acknowledged. (Even in her glowing foreword to Chouinard’s book, Naomi Klein has to make the disclaimer “I don’t endorse multinational corporations, even ‘green’ ones like Patagonia”.)

6. More humour. Less hubris.

None of this is an argument for cynicism or despair: it’s exactly the opposite. The power of consumerism and for-profit businesses to enact political change is limited because it should be. But that still leaves room for people to do the kind of work Newman’s Own does—apolitical, but utterly life-changing—and all while keeping the clear separation of church and state that is so often muddied by the purposeful companies of this world. It’s not only more effective—it’s better for the soul. I’ve written before about the question of taste in all this. I will never get past the fact that Dove sticking its logo over Covid nurses and tying it to a ‘Courage is beautiful’ brand message is tacky.

Too often, we see a false binary presented between purposeful marketing and good old-fashioned funny marketing that gets on with the job of selling things in an entertaining way. Anti-purpose people have lamented the dearth of funny ads in awards schemes, and the related rise of earnest, join-the-movement morality tales. There is some truth to that, but Newman’s Own is a reminder that the two aren’t mutually exclusive. What we need to rediscover is a lightness of touch: an ability not to take ourselves too seriously, even while knowing that life can indeed be serious.

Above all, we should rediscover the true locus of purpose: not in boardrooms, PowerPoint presentations or supermarket aisles, but in living rooms, pub conversations, community organisations and voting booths. We all yearn for a sense of purpose, but it’s usually something that reveals itself as you muddle through life. Paul Newman ended up where he did by being open to the role of luck, humble in the face of big challenges, and never branding himself as a righteous leader urging everyone to #dobetter.

If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, maybe the road to Utopia is paved with decent jokes. More humour, less hubris. I should work out the Latin for that.

A few sources I found useful:

Washington Post (particularly the Brian Mittendorf contributions)

The Indicator (NPR) on the details of the tax exemption

Carl Rhodes in The Guardian

Very thought provoking Nick. I am a fan of getting behind the headline. We live in a world of sound bites and short attention spans. So I’m grateful to read your piece. The Paul Newman story is also one that deserves a much bigger audience. Maybe a film about it?

Thanks for your ongoing writing for the good of people’s thinking with their own heads. Thanks in particular for sharing your sources: it’s a great mark of intellectual honesty and generosity.