Good for nothing

In the age of late purpose, we may have entered the strangest phase of all: purpose nihilism. But there is a way out.

For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Consider this post a significant milestone in the great purpose journey, in that I’m identifying the emergence of a strange new phase: purpose nihilism. Stranger still, I’m recasting myself as Mr Positive or even Mr Idealistic, despite not having changed my views—it’s just the goalposts keep shifting.

Towards the end, I’ll return to the theme of my recent Patagonia / Paul Newman post—namely, hubris versus humility/humour. I think these polarities offer a useful way to navigate the world of ethics (and ultimately effectiveness) in advertising—one that could work for the BrewDogs, BlackRocks and even Sam Bankman-Frieds of this world. I will grandly call this the Hubris Heuristic—more on that later.

For now, please adopt the unamused emoji face (my favourite emoji) as we dive headlong into BrewDog.

1. So it be

I’ll assume readers are familiar with BrewDog’s ‘anti-sponsor’ World Cup campaign—a loud protest at the human rights record of Qatar, and a loud promise to give the profits from sales of its Lost Lager to unnamed 😒 human rights charities for the duration of the World Cup. The campaign was loudly called out for various forms of hypocrisy: from BrewDog continuing to supply beer indirectly to Qatar (they since promised to donate those profits too), to BrewDog profiting greatly from showing and promoting the games in its bars (despite a previously ‘purposeful’ positioning of being against sport in bars), to BrewDog generally being deemed problematic when it comes to respecting the rights of its own staff.

I won’t go into the details of these hypocrisy claims, because for me they’re not the main problem. Yes, it’s annoying when brands say one thing and do another, but hypocrisy is a hard thing to eliminate entirely. Even if BrewDog showed none of the games, or donated profits from every beer, meal and soft drink for the duration of the tournament, they would still be open to the hypocrisy charge on some level—probably with greater focus on the BBC documentary stuff. (I’m making no accusations on that front, just noting these charges of hypocrisy would persist.)

Hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue, as a French writer and moralist once said. In dressing up self-interest as purpose, we at least acknowledge that some basic idea of virtue exists. Maybe we have to tolerate a certain amount of hypocrisy if we want businesses, and people, to do some limited good in the world.

But I think what *really* annoys people is something more than hypocrisy. It’s the sense of moral grandstanding—a phenomenon that has been the subject of academic research. The linked paper isn’t about branding in particular, but it’s worth reading because it highlights the negative externality of all purpose branding—the way it fosters cynicism and weariness around important issues (even if it ‘works’ for the brand in question). The authors note that moral grandstanding is associated with grandiose narcissism: readers might recognise this as the signature tone of most purposeful brands.

For me, this is the crux of the problem—and it’s partly a communication issue, which puts it in the wheelhouse of advertising and branding. What aggravates people about these campaigns is not the attempt to do good, or even the attendant hypocrisy. It’s the self-celebration and self-heroisation: the sense that the real motivation is status-boosting, not altruism. Yes, it gets worse the more you dial up the hypocrisy. But even genuinely good and unhypocritical people tend not to trumpet their virtue as loudly and relentlessly as these brands do: it’s one of the signs they are good people.

This is the foundational problem with purpose—it’s built into the concept in a way that can’t be removed or reprogrammed. It’s one thing for corporations to claim they do good things for society. It’s quite another for corporations to claim this is the reason they exist. That extra step is the seed that has grown into a thousand deluded ads and tortuously reverse-engineered purpose statements.

It’s not the hypocrisy, it’s the hubris.

We will return to this later.

2. Sympathy for the nihilists

For now, let’s look at some of the reaction-to-the-reaction to BrewDog.

Mark Ritson wrote a typically incisive piece in Marketing Week, where he called out critics of BrewDog for missing the point—the outrage is part of the game. It’s about cutting through and creating salience, which ultimately drives sales. The public isn’t carefully fact-checking each poster. They just see a big logo and brash headline, and get a vague reminder that BrewDog continues to exist. And it works—there’s a reason BrewDog has been one of the great commercial success stories of recent years.

I agree with this as far as it goes. Mark Ritson writes about marketing effectiveness and I don’t blame him for writing about BrewDog solely through that lens. It’s clear that BrewDog has been a remarkable success story, and its single-minded branding has been a major part of that. The fact that it aggravates people is indeed part of the point—disruptors gonna disrupt.

But Ritson’s piece is a counter-argument to an argument that I’ve not seen many people make. No doubt there are some denizens of LinkedIn who argue that the anti-sponsorship campaign won’t be commercially effective. But nearly all the backlash I’ve seen relates to the ethics, not the effectiveness. People are angered by the hypocrisy and the way yet another serious issue has been hijacked by a self-serving brand. The claim that this works is not an answer to those critics.

It’s also not engaging with the reality of the situation, at least if you take James Watt’s tweets as offering some insight into his state of mind. (I guess Ritson would argue it’s all part of the Baudrillardian simulacrum.) But it seems clear that BrewDog and its ad agency genuinely believe this is a positive, win-win initiative that has received unfair criticism. If James Watt’s defenders in the marketing world are winking to him and saying he’s an evil marketing genius who knows how to deploy vacuous tropes to shift product, then I’m not sure he’ll welcome his new allies.

As I’ve said before, my opposition to Purpose is agnostic as to whether it works commercially. Most of the time, I think it doesn’t—and attempts to prove otherwise have floundered in the face of unhelpful evidence. Either that, or they rely on shifting definitions of what purpose means—if BrewDog works, should we take it as proof that real purpose works, or that fake purpose works? Would it work better if it was real, or does it need to be fake in order to generate the outrage and salience?

These are interesting questions, but they bypass an entire hemisphere of the debate. If you’re going to engage with Purpose on its own terms, you can’t treat it solely as a marketing effectiveness question. The approach is based on the idea of doing well by doing good. If the only way to do well is to forget the doing good part, then you’ve ended up in a strange and dispiriting place.

3. The purpose circus

Yet this is where we seem to be. There’s an extreme point at either end of the horseshoe where purpose advocates and purpose sceptics almost overlap.

Purpose advocates are so keen to prove it works commercially that they regard ethical objections as annoying background noise. So Cadbury’s wins the new purpose category at the IPA Effectiveness Awards, based on a case study full of commercial metrics, and anyone mentioning tax avoidance or asking for more specific evidence of social impact is seen as churlish. Equally, anyone questioning ‘punks with purpose’ BrewDog is seen to be in denial about the commercial success. Stop going on about the ethics. If it works, it works.

At the same time, most purpose sceptics insist the industry needs to forget about saving the world and get back to selling. Stop going on about the ethics. If it works, it works.

I’m happily identified with the second camp, but I’ve always tried to make one nuance clear: the ethics matter, but purpose is the wrong way to frame them. Most of the ethical responsibilities of business will be in tension with the profit motive, rather than aligning with it. When for-profit business delude themselves and others into believing they are for-purpose, moral mayhem ensues.

Like Mark Ritson, I am absolutely in favour of brands embracing P.T. Barnum-style showmanship to generate salience. But when politics becomes part of the show, you’re encroaching on a different space. This is part of the Ancient Greek meaning of hubris—it involves a transgression into another realm. In legal usage, it was used to describe certain categories of crime, including assault and theft of public property. Yes, we can cleverly recognise a world where Baudrillardian brands are marching into the civic realm and turning politics into a cynical clown show, but it doesn’t mean we have to (fucking) accept it.

4. Effective nihilism

All this ties in with another interesting story—on a scale much larger than lager.

Most readers will have heard of Sam Bankman-Fried, now holed up in the Bahamas after the collapse of his cryptocurrency exchange, with billions in customer deposits up in smoke—a downfall on the scale of an Enron or Bernie Madoff.

He’s a fascinating character, almost certainly on what is called ‘the spectrum’, and widely known for his association with the effective altruism movement—an approach to philanthropy that aims to remove the sentiment from charitable giving and focus single-mindedly on results. Bankman-Fried was a prominent public face of effective altruism, living a modest lifestyle while making enormous donations to left-leaning social and political causes.

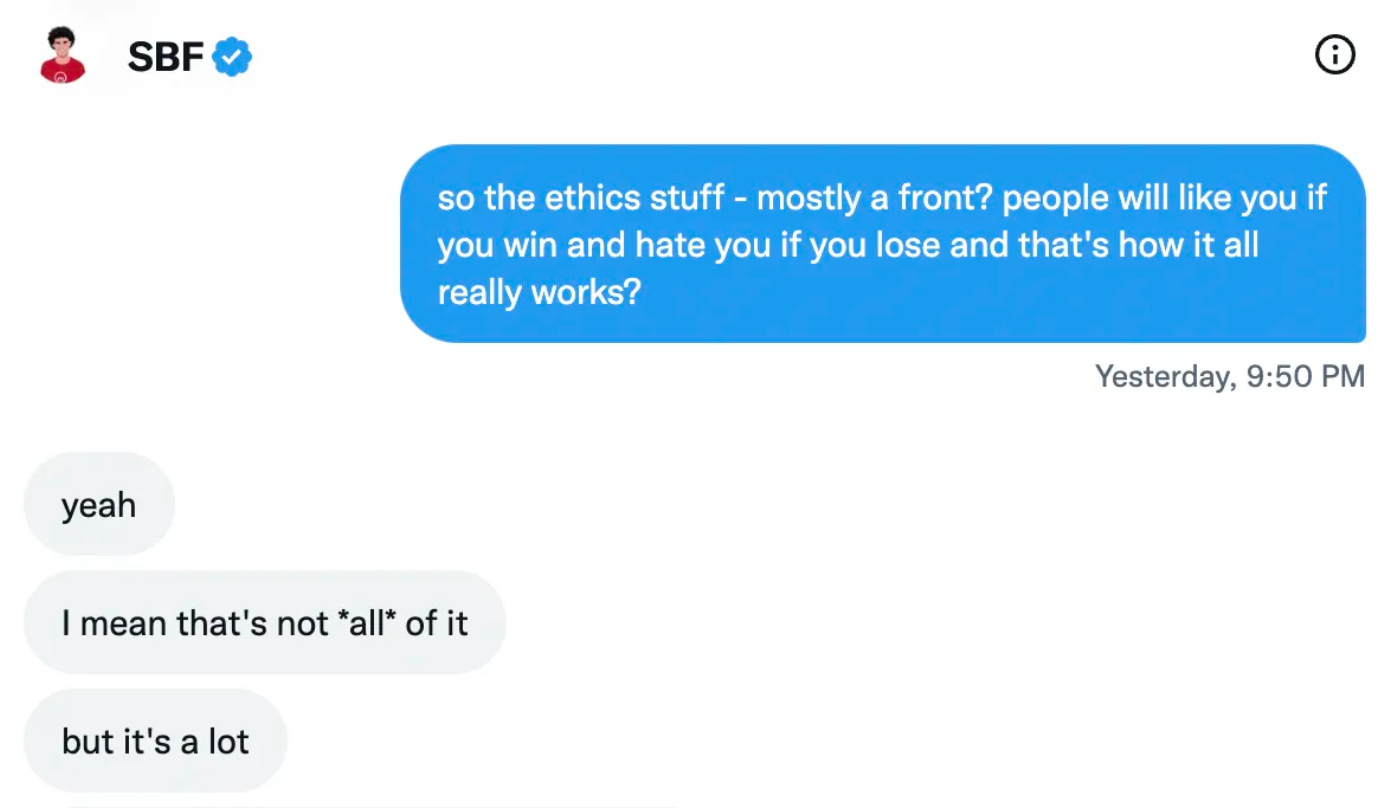

Once you’ve finished reading this post, I urge you to read the recent WhatsApp exchange between Bankman-Fried and a journalist at Vox, in which he reflects on recent events. It’s a gripping insight into how easily idealism can collapse into nihilism, or how one apparently acts as cover for the other. Bankman-Fried appears to see a world in which everyone plays the same game of parading virtue for personal gain, the only difference being that some end up as winners and others (like him) as losers. He ends up channelling Omar from The Wire, if the story took place in the white-collar (or baggy t-shirt) world of Cannes and Davos. The game is the game.

In truth, I suspect Bankman-Fried is not quite the moral nihilist that comes across in this exchange, which took place at a time of high stress. But I can’t help wondering how many of the leading voices in the purpose world might feel the same thing deep down. Sure, we talk about purpose, but it’s a BrewDog-eat-BrewDog world out there. Do whatever it takes, say whatever it takes, take the hits, bank the attention, cash out the salience. Just don’t be the guy in the Bahamas when the music stops.

5. Noble Cause Corruption, revisited

I will finish by circling this back to hubris and suggesting another way forward.

But first, one more thought on effective altruism, whose reputation may not survive recent events. I actually think there’s some sense in the idea of it. Having worked in charity advertising, I know how irrational our giving instincts can be—show us a picture of a child in need and we’ll weep as we hit donate; show us 10,000 children in need and we’ll begin to tune out. Show us a mosquito net and we’ll shrug; show us a guide dog and we’ll melt. If we can decouple our emotional instincts from our philanthropy, it could realistically lead to better outcomes.

But while there’s merit in the idea, the movement seems fraught with risk—and with potential for hubris. In particular, the focus on long-term outcomes (captured in Will MacAskill’s book What We Owe The Future) creates fertile territory for an affliction I’ve discussed in an earlier post: noble cause corruption.

I wrote about it in the context of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos—and it’s appropriate to return to it on the day she is sentenced (probably not long after this post goes out). Briefly, it’s the idea that people find it easier to justify morally dubious actions if they are convinced that their ultimate cause is noble. In the case of Elizabeth Holmes, she appeared so wilfully deluded about the life-saving potential of her work that it was justifiable to ‘move fast and break things’ in order to get there.

It’s easy to see how effective altruists could wander, or consciously leap, into the same trap—especially with the focus on a distant time horizon. In a cold, utilitarian calculation, does it matter if Bankman-Fried cuts a few corners and spins a few yarns, if he’s going to give the money to good causes? (For now, let’s leave aside that those causes included the Democratic Party and news outlets like the New York Times and Vox itself—the altruism was buying him a place in the big league, on conference stages with Mark Zuckerberg, Volodymyr Zelensky and, oh yes, Larry Fink.)

But I will say one thing for effective altruism. At least the word effective is being applied to the altruism. Going back to the effectiveness of brand purpose, and of the BrewDog campaign, the adland conversation quickly defaults to commercial results any time the question of effectiveness is raised. It’s understandable—that is meant to be the job after all. But the premise of Purpose is that it’s about more than that. Somehow we end up in the worst of all worlds: a bleak nihilism where purpose is just another marketing card you can play—it doesn’t matter if it’s bullshit as long as it works. The game is the game.

6. The Hubris Heuristic

In my new guise as Mr Positive, I don’t think we have to be this cynical.

I’ve seen BrewDog defenders (including James Watt himself) arguing that of course their anti-sponsorship initiative is insufficient and of course they’ll be making plenty of profit anyway, but we live in an imperfect world and at least they’re doing something. Which is more than some other brands have done. Isn’t that better than nothing?

When I read arguments like that, I think—OK, why not make that the ad? Don’t save the honesty for deep in the Twitter thread and pre-scripted PR defence. The truly ‘punk’ thing to do would be to make it the headline.

Creatively, it’s harder to pull off. Brands are more comfortable being the heroes issuing powerful rallying cries. And ad agencies know that script by heart and can write the ads in their sleep. But there would be something genuinely ground-breaking about being a brand that levels with people about this stuff, rather than doing the righteous moral grandstanding that has become so familiar.

Here’s an alternative take that I tweeted when this whole fuss started:

WE’RE SH*T AND WE KNOW WE ARE

Honestly, we can’t wait for the World Cup. But we also don’t feel great about it and will be donating 20% of all our profits to human rights organisations. We know it’s not good enough, but it’s something. Support these actual do-gooders: [PROMINENTLY NAME THE CHARITIES]

That would be different at least. Still a big, football-themed, ‘punk rock’ headline. Still scope for some salience-building controversy when people complain it’s making light of the situation. But at least it’s honest, grounded and not entirely full of shit. And, importantly, it makes the charities the heroes, rather than the brewer of beer.

Like I say, this stuff is creatively challenging. But ad agencies are meant to be good at creativity, and I think they should give better advice to people like James Watt. Look, we know the punks-with-purpose stuff works for you, and we can keep playing that game. But you also seem genuinely put out by the bad reaction that you keep getting from certain quarters, and we believe all this does affect your brand long-term, even if it pays off short-term. It puts a target on your head and sets up a pride-before-a-fall narrative that leads to things like the BBC documentary. So we’re recommending a different approach where you dial down the hubris and dial up the humility, plus a bit of humour.

Oh cool, you’re talking about the Hubris Heuristic, says James Watt, and someone sends me a lifetime supply of beer.

I am getting carried away, but you get the idea. I think ad agencies and brand managers can apply the hubris heuristic to everything they do. Does this comes across as moral grandstanding? Are we making ourselves the hero? Is it a bit much? A bit 2016?

It’s more than a tonal change, because when you truly cut out the hubris, you cut out the transgression from one realm to another. There’s no pretence that this makes BrewDog a purposeful hero—the human rights charities are the ones with the purpose. BrewDog is making a donation while concentrating on its core game of selling beer to people who sometimes want to watch football in this godforsaken, nuclear-brink, cost-of-living-crisis world where there is precious little joy and community to be had. That’s not a horrible thing to do. Yes, they’re morally compromised, but aren’t we all.

Way back in my first post on this Substack, I wrote that people used to laugh at ads—now they laugh at ad agencies.

They’re still laughing, and it’s partly because of things like the BrewDog ad (probably unfair the way I’ve dwelt on it—could be so many others, and I admire lots of things about BrewDog and its agency). But hubris always cries out for humour. When a brand marches righteously towards its soapbox, we long for the banana skin—it’s human nature, and ad agencies should be better at understanding it.

In all of this, I have asked myself a disturbing question: Wait, am I morally grandstanding? Am I trying to signal my superior ethical sensibility by writing about all this stuff at exhaustive length, before returning to the day job?

I hope not, but I’m no doubt as susceptible as anyone else. I will continue trying to make the case against hubris and in favour of humility/humour. And if a bit of the usual Substack hate is the price I have to pay for massively raising awareness of the purpose issue, then SO BE IT.

Further reading:

Mark Ritson in Marketing Week

(hope he doesn’t mind the photo—nailed the Elizabeth Holmes look)

UPDATE: Elizabeth Holmes has been sentenced to 11.25 years—miserable ending to a 21st-century parable of purpose. Here is my earlier post, or read John Carreyrou’s book for the full story.

Very good. I would be harder on Ritson though. Just because you can doesn't mean you should. For Ritson to merrily embrace this cynical crap is disappointing. But if it all hastens the end of this trend then maybe it serves a purpose.

One of the best things I have read on purpose for a long time. Inspired a new (qualitative) formula : Outrage = hypocrisy x hubris ?