Notes not from Cannes

On 'post-purpose', empowered judges, devaluing creativity, alt text facepalms, diverse juries, progressive ads, Musk, and all the creativity never celebrated.

First, it’s fair to ask—why write about Cannes at all? Isn’t it just a pay-to-play circus generating vast amounts of revenue while reputation-washing the ad industry by presenting a feel-good shop window that’s ludicrously detached from the day-to-day realities of advertising, design and commercial creativity?

Well, yes. But, judging by last week’s events, it’s also undeniably growing in influence and relevance. The inclusion of Cannes-bashing commentator Mark Ritson could be seen as a case of ‘keep your enemies close’, but it’s also a welcome sign of reconnection to the realities of marketing. And if nothing else, the appearance of Elon Musk is testament to the influence that Cannes now wields. If you want to talk to the big players in advertising, tech, and multinational marketing, Cannes is the place to do it.

As someone who values creativity, I think it’s also worth paying attention to anything billing itself as the International Festival of Creativity. After all, even if many creatives roll their eyes, it affects the way clients and the wider world perceive what we do.

So, I will write about Cannes. And what follows are eight notes that came to mind as I’ve observed events from afar.

1. ‘Post-purpose’—saying it won’t make it so

“We live in a post-purpose world,” reports Marco Venturelli, Chief Creative Officer at Publicis and president of the Outdoor category, quoting one of the judges on his panel. Mark Ritson agrees we’re now in the “post-purpose era”, according to Marketing Week. Elsewhere, LBBOnline reports that “Celebrating commercial creativity was in, as was questioning purpose—it was to be celebrated but also interrogated.” The same report expands on Marco Venturelli’s comments: “[Venturelli] also drew attention to the need for purpose to connect with sales, saying that we need to remember that ‘selling is okay’; it was a big topic of discussion among his jury with many saying that the industry might now be ‘post purpose’ at large.”

The renewed talk of selling being ‘okay’ has to be welcomed. And the idea of interrogating purpose seriously should be embraced by purpose people as much as anyone. If the claim is that the work is having a positive impact on society, then it’s important to examine that rigorously, rather than on the basis of an emotive case study video. Unfortunately, judges chosen for their creative expertise aren’t in the best position to do that effectively—which is why it’s so important to have separate charity and social purpose categories judged by people who bring expertise in social change, and following a different judging process where rigorous questioning is the norm, rather than coming from one or two outliers on the creative juries who take it upon themselves to do some Googling and are usually dismissed as heartless cynics.

But talk of post-purpose remains just that for now. At the same festival, Richard Edelman, CEO of the world’s biggest PR agency, was urging brands to get more involved in politics. “Politics is not something to run away from as marketers; politics is something to wade into,” said Edelman (as reported by WARC). “It is a competitive advantage if you understand who your audience is.”

All this is based on research that asks consumers how they make buying decisions, eliciting answers that have little bearing on how consumers actually make buying decisions. According to Edelman, “A majority of consumers say brands have to take a stand: on climate (by five to one), on fair pay (by four to one), on race and diversity (by two to one).” Similarly: “There has been a jump in nationalism, with eight in ten people choosing not to buy brands from particular markets—for example, Americans not buying Chinese brands, or vice versa.”

When a survey asks whether ethics are important to you when buying a product, the natural answer is always ‘yes’. But the best measure of what makes customers buy things is… the things customers buy. One of the biggest Gen Z success stories in recent years is Shein—the Chinese-owned fast fashion chain that is thriving in a world where Edelman’s research says people are boycotting Chinese brands and demanding brands take a stand on climate. Chinese-owned TikTok has become the platform of choice for this politically conscious generation. Alongside Shein and TikTok, other top-ten brands for Gen Z include Amazon, YouTube and (at number one) Nike—which Ethical Consumer criticises for its use of forced labour, gender discrimination, and lack of support for a fair wage.

Edelman must be smart enough to know this, but purpose and purpose-washing are such a useful revenue stream that no one wants the tap to be turned off. Edelman itself has worked with ExxonMobil, the Saudi government and the Sackler family—and Adam Lowenstein has written in the Guardian about how preposterous their talk of ‘trust’ really is.

Meanwhile, for all the judges’ comments, purpose still looms large among the winners at Cannes. After years of favouring feel-good work, it’s become a default expectation among judges that the top awards aren’t ‘just’ for creativity, but for creativity that ‘makes a difference’ or ‘moves things forward’. When a brilliantly funny, exceptionally crafted or commercially popular ad breaks through, it’s seen as purpose graciously making space on the podium for the stuff that’s ‘just’ selling. When that mindset changes, we might finally be ready to talk ‘post-purpose’.

2. ‘Empowering’ creative judges to… judge creativity

Speaking of which, there was an interesting aside from Simon Cook, CEO of Cannes Lions. “Jury presidents felt empowered by Cannes not to just reward work that was doing good,” he said on the Campaign podcast. Campaign also reports: “Jurors at this year’s event were given guidance by the awards organisers to scrutinise more closely work aimed at improving the world.” Jury president Simon Vicars is quoted as saying: “Previously there was an ‘inability to question the purpose of the work because it appears you are questioning the purpose itself’”.

I find this both encouraging and frustrating.

Encouraging, because I’ve argued time and again that awards bodies have a responsibility to make sure judging is based on the same criteria that are advertised to paying entrants, right up to the top awards. If you accept money for a fast food or airline entry on the basis that it will be judged on creativity, then you can’t allow judges to invoke their own personal criteria when it comes to the big awards (“It’s brilliant, but I just don’t think it’s the right signal to award a meat brand, an airline” etc.) When a judge says “This cause just means so much to me”, it should be met with an understanding nod, but also a clear reminder that this isn’t what’s being judged—there are other categories where social impact can be judged more rigorously, rather than just on vibes. If a vegan judge wants to abstain, that’s valid, but if they’re proudly marking down the McDonald’s entries that are paying for their hotel, it’s unethical.

It’s frustrating because no such reminder should ever be needed. Creative judges shouldn’t need to feel ‘empowered’ to do the basics of the job. But I’ve sat on Black Pencil juries at D&AD and I know that some degree of empowerment is needed. Purpose is so deeply baked into some people’s mindsets that the ‘Shouldn’t we just judge on creative excellence?’ person is usually seen as the awkward contrarian. It shouldn’t be on them to ensure the awards body does the right thing by its entrants.

And that’s what it’s really about: empowering entrants rather than judges. They’re the ones who fork out large sums to keep the show on the road. Their voices should be top-of-mind in the judging room. If creative entrants aren’t being judged on creativity, refund the money and don’t call it a creative award.

3. Creativity devalued

None of the above is simply about who gets the gongs. It’s about the wider effect on the industry—because it ends up having a corrosive effect on the idea of creativity itself.

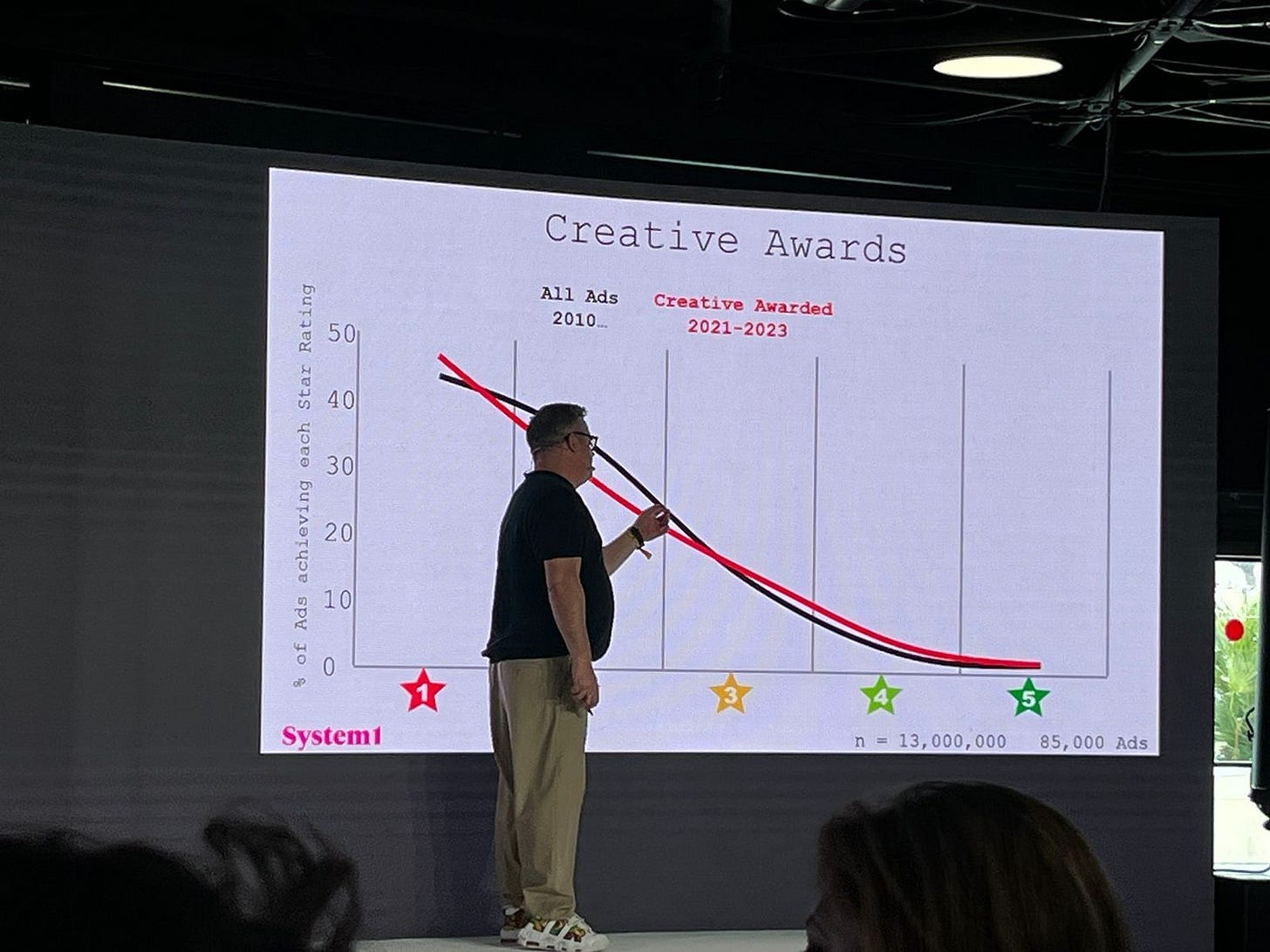

Mark Ritson arrived at Cannes for the first time to bring a welcome reminder that the award-winning stuff over the past 15 years has become increasingly detached from the work the public actually likes.

The trouble is, all this is framed as ‘Creativity isn’t enough’. Or even worse, in the accompanying Marketing Week report, “Creativity is distracting marketers from what matters”.

Creativity matters! And the problem in the last 15 years is that its own award schemes have become purpose awards schemes, which accounts for the increasing detachment from reality. Purpose is the distraction that should be called out in the headlines, but instead we get talk of a Crisis of creative effectiveness or entire articles titled Creatively awarded ads, once effective, are now officially average that never once mention purpose.

On one side, creativity gets elbowed out of its own awards schemes—“Creativity means something different now” says the CEO of D&AD, as though apologising for not being purpose-y enough in previous decades. On the other side, creativity takes the blame when those awards schemes become increasingly unrepresentative and irrelevant. And all the big tech companies and clients in attendance go away with the impression that creativity isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, when they should be full of renewed belief in the power of creativity to drive business success and elevate genuine good causes.

Marketing effectiveness people and creative people are on the same side. It would be great if creative festivals could re-centre creativity, in deed as well as word, and champion it loudly.

4. Alt text facepalms

For this one, I’m just going to reproduce what I wrote on LinkedIn. Positioned at the entrance to the main venue at Cannes, this campaign is a reminder of how profoundly unserious ad agencies can be when it comes to actual social causes.

(For previous post, see Have purpose agencies forgotten how to do charity ads?)

5. Diverse judges and convergent judging

An incidental point, and a tricky one to make without sounding like I’m somehow against the basic idea of diversity and inclusion. It’s particularly tricky when it involves the admirable Cindy Gallop and fellow juror Ren Rigby. (I saw Ren talk in Birmingham recently and it was both creatively and personally inspirational).

But I still find the sentiment of the above tweet weird. The most common argument brought forward for diverse judging panels is that those judges will bring radically different perspectives based on a wider range of lived experience. On the face of it, you would think this would make consensus slower to arrive at, rather than faster than ever. The argument seems to be that, by virtue of their diversity, all these people are more ideologically aligned, as well as being more open-minded and better at listening than your average juror—which seem like big generalisations to make about large ethnic and gender groups.

I’m very much in favour of judges being open to changing their minds in judging sessions—I think the best sign of a good judge is if you manage to change someone’s mind and likewise have yours changed at some point. But in my experience of judging, that’s never mapped onto the gender or ethnicity of the judges in question. There are plenty of introverts, extroverts, good listeners and terrible listeners on all sides. And if agreement comes too easily, it could be a sign of something awry (though I can understand the urge to get out the basement and back into the sun).

6. Progressive research

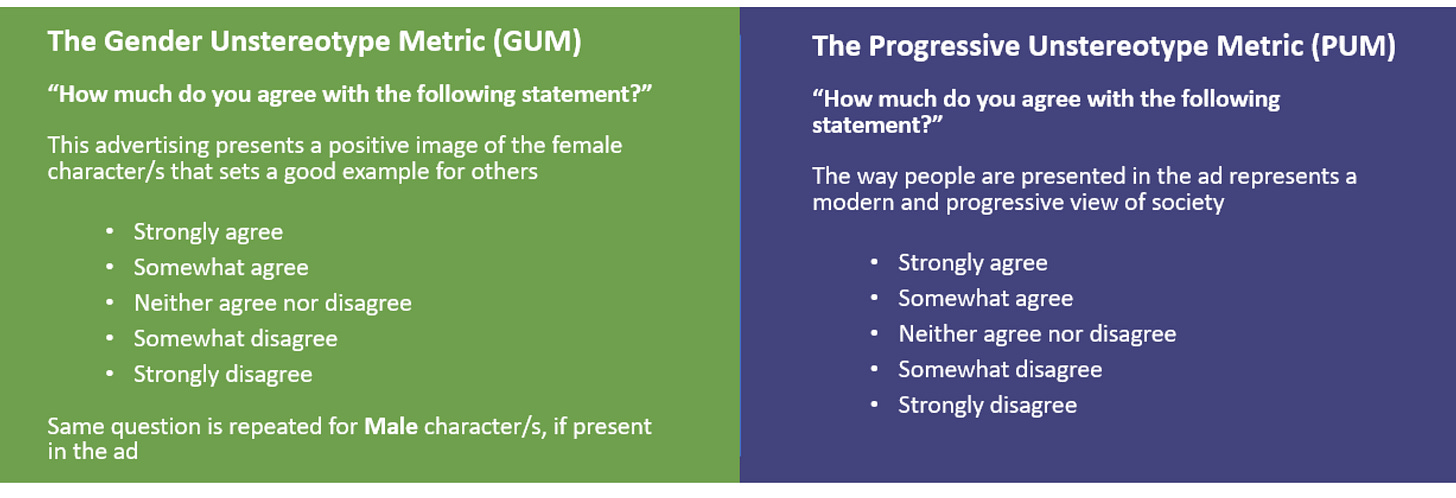

Not unrelated to the above, Cannes saw the launch of new research titled The Business Case for Progressive Advertising, produced by the Unstereotype Alliance (an industry body convened by UN Women). So far, the full research hasn’t been released (just this two-pager), but the suggestion is that ‘progressive’ advertising leads to a 16.26% increase in long-term sales over one to two years, a 52% rise in pricing power, a 43% rise in purchase consideration, and a 29% rise in customer loyalty—all huge commercial claims that ought to have Chief Financial Officers rushing to the marketing department to demand they get on board.

It’s not yet possible to dig deep into the research, but two things seem immediately apparent.

First, ‘progressive’ is a broad term for the researchers to use given that they’re measuring the very specific issue of casting and storytelling in advertising (using the metrics above). Usually, ‘progressive’ has broader connotations. For example, a glance at Wikipedia offers this: “In the 21st century, progressives continue to favour public policy that they theorise will reduce or lessen the harmful effects of economic inequality as well as systemic discrimination such as institutional racism; to advocate for social safety nets and workers’ rights; and to oppose corporate influence on the democratic process.” It’s hard to see many ads doing that kind of progressivism, especially when it comes to the last point.

But even once you’ve defined the terms, there seems to be an obvious question of correlation vs causation. Does progressive advertising lead to commercial success, or does commercial success enable you to do more progressive advertising? Or does neither lead to the other, but they nevertheless correlate in some meaningful way? And where do cases like Bud Light fit in, where progressive advertising seemed to lead to a sustained business downturn? Maybe the research tackles all of that. For my part, I’ve written in The Road to Hell about how casting in advertising has indeed been a positive contributor to social change (in the days long before purpose), albeit one that can end up creating new stereotypes of its own. So I hope there’s something to the report, even if the broad framing of the title seems unhelpful.

7. The meaning of Musk

When it comes to Musk, it seems the most interesting aspect of the story is not about anything he said, but the fact he was there at all.

Following the exodus of big brands when Musk took over Twitter, and months after the ‘Go fuck yourself’ message that he broadcast from the stage in 2023, the simple fact of his presence at an advertising event speaks volumes. For all Musk’s talk of a ‘public square’, Twitter resembles Times Square at best, except with so many billboards that there’s hardly any square left. Everything about the way it operates—the boosting of loud voices, the amplifying of extreme opinions, the incentivising of news headlines to become provocative clickbait, the polarisation of politics that has resulted… all of it is driven by the ad-funded model, and that was the case long before Musk took over.

For a while, Musk’s anti-advertising stance appeared to hint at a new model, maybe driven by paid membership tiers or micropayments for content providers. But none of that has fully materialised, and Musk knows X needs advertisers more than advertisers need X. So here he is at Cannes, pitching to all the brands who want to ‘lead the conversation’ on everything from declining mental health to our dysfunctional politics—all while exacerbating those problems by their very presence on social media platforms, most of which now exist in service of advertisers more than users.

Someone should write a new Bonfire of the Vanities about it all.

8. The creativity never celebrated

Finally, a small flag-wave for the vast hinterland of creativity that never gets anywhere near Cannes. At least with non-profit D&AD, there’s the semi-realistic prospect of forking out somewhere in the low hundreds for a single entry, with discounts for smaller businesses. But in the case of Cannes, you’re often forking out more than some campaigns would cost in the first place: €1,075 for a poster, or €650 if you get in early. Look at the agencies who enter purpose campaigns across multiple categories and you’re looking at tens of thousands of pounds that might have been invested in the supposed purpose—all promoted by the ubiquitous case study videos that many entrants pay up to £20,000 to produce.

This is not a sign of judging being taken seriously. Imagine lawyers cuing up Coldplay when making the closing defence case for their client. Imagine contestants on Dragon’s Den making their pitches to inspirational piano music, with the ‘dragons’ faced with a barrage of Sigur Rós whenever they ask about the sales figures. Case study videos have become an industry in themselves—ads for ads. It’s ridiculous that juries are assessing work on this basis, and impossible for low-budget entrants to send in a poster and expect a fair hearing.

I don’t see what’s stopping Cannes or D&AD from making changes. No background music in case study videos. No news clips from a random news channel at 3am talking about your campaign. No montages of ecstatic tweets that no one can fact-check. The default should be to enter the work and nothing more. In the exceptional cases where it needs further explanation, either write it down or do an informational video—the work, the voiceover, nothing else. Let the best creative work compete on a level playing field, without the absurd PR spin to which judges are as susceptible as anyone else.

Of course, it won’t happen. But in the meantime, I look around at the brilliant creative work coming out of smaller design and branding studios, or specialist charity agencies, or in-house agencies (remember that nice ‘Lights, camera... action’ ad that ITV’s in-house agency did?)—and I wonder if there’s any international festival of creativity that recognises even a fraction of it.

Anyway, onwards. For anyone who doesn’t know, I have a book about all this. I’ve greatly appreciated all the feedback and invitations to talk about it in various places—I’ll be appearing on a few podcasts imminently, and you can find more links here:

Contagious interview

Marketing Week article

WARC article

WARC podcast

Creative Review article

Absolutely fantastic read, so much to think about.

This, however, annoyed me. Really sloppy questionnaire writing in the The Progressive Unstereotype Metric question. The use of modern AND progressive. Just use one or the other. If they mean the same ( I am not sure they do) there is no need for both. If they mean something different then have two questions. My first boss in market research would have hauled me over the coals for that!

"How much do you agree with the following

statement?"

The way people are presented in the ad represents a

modern and progressive view of society

An epic read.👌🏽