Have purpose agencies forgotten how to do charity ads?

With commercial clients edging away from purpose, ad agencies may need to relearn how to do great charity advertising. And it's not easy.

Regular readers will know one of my problems with purpose is how it involves commercial brands adopting social causes in a way that undercuts the actually purposeful people in the not-for-profit sector. This forms part of the argument in my upcoming book The Road to Hell, which I plan to shout about in my next post.

In recent months, there are signs that the purpose high tide may be receding, with businesses nervously trying to relocate their commercial swimming trunks before becoming too exposed. (Apologies for this analogy.) But there is a way for ad agencies to keep doing emotive, powerful, socially purposeful stuff—by doing it for the clients who can actually back it up, without the need for a torturous dismount that links the story to washing powder or deodorant at the end.

Those clients are called charities. And in this post, I want to talk about three campaigns that suggest charity ads may be making a comeback. Then I want to talk about why the purpose template can’t just be cut and pasted back onto charities—it needs to be more serious and sustained than that.

1. Say what you see

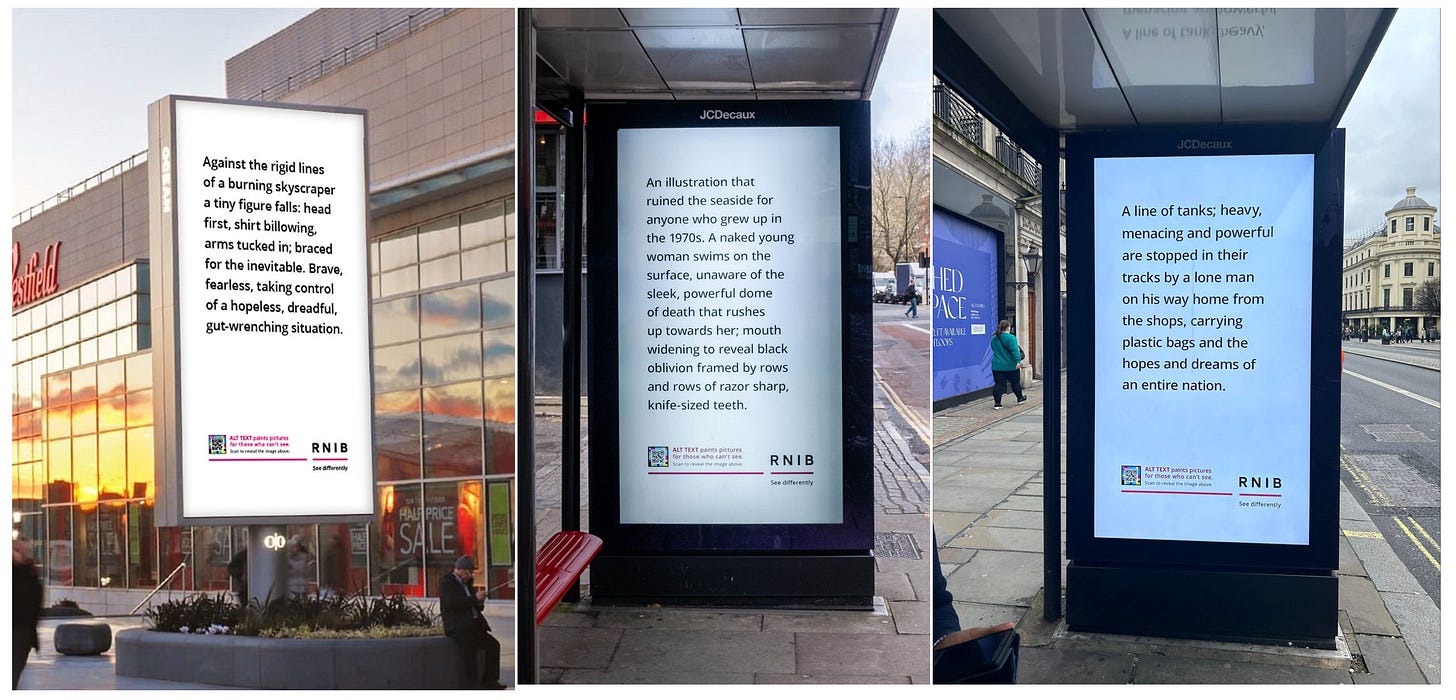

So first up are the RNIB ads pictured at the top of this post.

The idea is to promote the use of alt text—the alternative text descriptions of images for blind and visually impaired readers that have become best practice online. As the official RNIB account says: “Alt Text, a written description of an image, picture or photograph, is vital to many of the 2.2 million people in the UK with sight loss—it allows screen readers to read out descriptions of images, so that everyone, regardless of sight, can fully participate. But Alt Text is often either really poor quality or forgotten about entirely. Writing Alt Text for every image you post gives everyone a fuller picture.”

The posters attempt to do this by offering evocative descriptions of iconic images including (left-to-right) the falling man on 9/11, the Jaws movie poster, and the Tiananmen Square lone protestor. And there has been plenty of warm reaction on social media, praising the evocative writing and the ‘power of words’.

The trouble is, all this amounts to a poor guide to writing alt text. As all the writing guides will tell you, the whole idea is to offer concise, informational descriptions without editorialising (i.e. adding your own steer to the desired emotional response or ‘meaning’ of the image). Rather than a chance to flex your creative writing muscles, it’s a service to blind and visually impaired people, allowing them to scroll through an article or social media stream with brief, neutral descriptions that enable you to read at speed and form your own judgments about the content.

Even on a functionally descriptive level, you can see how these ads fail.

The Jaws poster talks with some specificity about the naked young woman, but never mentions the literal presence of a massive great white shark—instead waxing poetic about a “sleek, powerful dome of death”.

The Falling Man poster presumes to know the state of mind of the man in question:“Brave, fearless [was he?], taking control of a hopeless, dreadful, gut-wrenching situation.” Surely the power of that image is the unknowability of that man or his state of mind. The alt text doesn’t even specify that it’s a man—just a gender-neutral “tiny figure”—and it’s worth noting that the image itself doesn’t show the building “burning”, which adds to the haunting calmness of it all.

Finally, the Tiananmen Square description is unnecessarily overwritten—do readers need to be told the tanks are “heavy, menacing and powerful”? Do we know the guy was on his way home from the shops? Was he carrying the hopes and dreams of an entire nation, or is that western-centric editorialising? For sighted readers, the photo simply shows a man standing in front of a row of four tanks, and we are free to infer the symbolism and meaning for ourselves. All readers should have the same privilege, without being guided by the hand of an over-enthusiastic writer.

OK, but RNIB were happy with it, so who am I to criticise? Well, as I tweeted this week, I’m surprised they were happy with it. From what I can glean on LinkedIn, it seems the agency, MullenLowe, approached RNIB with a speculative idea that was then signed off. It seems pretty likely that MullenLowe may have paid for some or all of the media placement too. So I can imagine RNIB might have been in a position where you’d be tempted to welcome the publicity, as long as it’s not something blatantly inappropriate or reputationally damaging.

Maybe they would also defend it by saying it’s not meant to be taken as a guide, but as an inspiration piece to ‘raise awareness’ of alt text as something worth taking seriously. But there are so many ways to promote that message without also spreading a potentially damaging idea of what represents helpful alt text. Can you imagine the number of Instagrammers or tweeters who might start writing lengthy, poetic text to demonstrate their writing chops, rather than to help the reader?

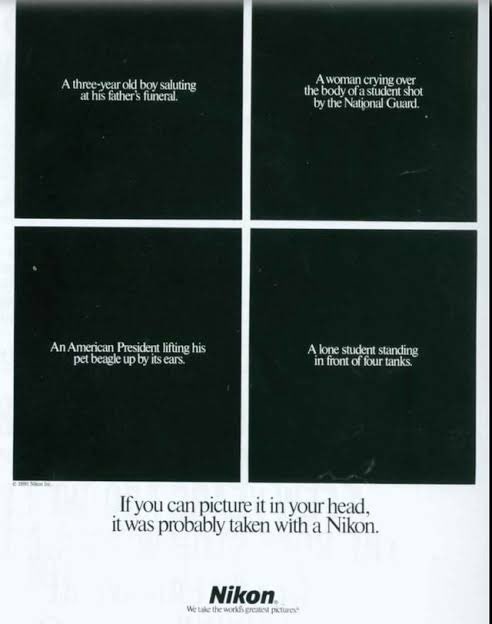

As someone pointed out on Twitter, the final irony is that this has actually been done better by a commercial client, where the copy is spare and precise, which makes it more powerful, not less.

2. Feel-good can feel comforting

So here I stride onto shakier ground.

Many people have welcomed this ad for World Down Syndrome Day by CoorDown, the National Coordination of Associations of People with Down Syndrome. And I can see why. It’s a powerful ad with a charismatic lead performance by Madison Tevlin, a Canadian actress and broadcaster who was already known for her stereotype-busting activism—and the message about never making assumptions based on superficial appearances is an urgent and welcome one.

The story is no doubt based on personal experience that I’m in no position to question. But I’m going to dare criticise aspects of the ad anyway, because they’re relevant to how you judge the success of a charity ad.

In this case, it’s clear that the ad is projecting a power narrative that is familiar from recent years—whether it’s Dove, Nike, Meet the Superhumans, or This Girl Can. And that’s fine, but in this case it comes with some uncomfortable downsides. Why are the parents in this ad portrayed as the enemy, when so many parents of children with Down syndrome are doing a heroic job with little support? (Bear in mind, all these parents are potentially among the most committed supporters of CoorDown and associated charities—not a great idea to alienate them.) And why are teachers portrayed as so bad at their jobs that they’re teaching Old MacDonald instead of Shakespeare, when so many teachers and carers are doing amazing work, and again form a key part the audience that CoorDown wants to enlist?

More broadly, given that the message is about never making assumptions, might this ad encourage the assumption that people with Down syndrome are surprisingly fine if people just get over their prejudices? The difficult reality is that only a small minority are able to live fully independent lives, and not because they lack a sufficiently empowered attitude or are held back by feckless parents and teachers—but because progress isn’t purely a matter of positive mental attitude.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t make feel-good, stereotype-busting ads. But sometimes I wonder who they’re really meant to make feel good. In this case, it’s clearly not parents or teachers. But maybe it’s the wider general audience who, despite the superficially scolding tone, find it oddly comforting to watch empowerment stories where relative outliers say “I am totally fucking fine! You’re the ones with the problem!” As in-your-face as that sounds on the surface, there’s a level on which it lets people off the hook. How many watch that ad and think “Woah, she’s obviously doing great! Phew! What I thought was an intractable and challenging issue is really just a matter of prejudice and perception on my part! OK, I’ll be better in future! Next issue!”

I’m exaggerating, but I think that’s part of the dynamic of so many of these empowerment narratives. And I’m not sure it does the related charities, or the people they help, that much good in the long term.

3. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before

Before moving onto wider thoughts, I want to mention this recent NSPCC ad, which was billed as them broadening out to explain the wider purpose of the charity—not only preventing child abuse and neglect, but providing long-term help to families of children growing up. The ad features a poem recited by actor T’Nia Miller, charting the journey of parenting from birth to leading independent lives.

I mention it not in order to criticise anything, but to note a strange effect of the purpose age. If you’ve never seen the ad before, watch it through—soaking in the vibe and aesthetic—and imagine how natural and expected it would be to find a commercial logo at the end. Maybe a washing powder—with you through the ups and downs; or a bank—maybe Lloyds or Nationwide in their poetry days; or a John Lewis or Marks & Spencer; or maybe a home insurer or investment plan. All could easily slot in with a little dismount at the end. And that pattern has become so familiar that it’s almost a jolt to see an actual non-profit logo at the end of this one.

To me, that seems like a problem for charities. How do you stand out in a landscape where commercial brands have planted their flags so firmly on tear-jerking stories, emotional poetry, social causes and timelapse birth-to-death dramas? In recent weeks alone, we’ve had a cross-generational father-son tale centring a porridge brand, a girl dancer ageing before our eyes to promote a radio brand, and a baby flashing forward through her entire life to advertise an airline brand—and that’s all just from one agency.

In a climate where so many commercial brands are hitching their wagon to the star of a social cause or deeply emotional life story, where does that leave charities? And where does it leave the ad agencies coming up with ideas for them?

4. Hard work

I think it leaves them with their own mess to clear up. And it doesn’t simply mean taking the purpose template and retrofitting it back to charities. When you’re doing ‘purpose’ for a commercial brand, it can be judged a success if you get sufficient traction on social media and plenty of free press coverage and awareness-raising hype. The aim is to raise the salience of the brand, and if you can do that by harnessing a social issue or making people cry, then all is fair in love and advertising.

But with actual purpose ads—charity ads—the stakes are higher and more serious. Raising awareness of the RNIB brand is one metric, but if it comes at the expense of misrepresenting an important issue, that has real-world effects. Winning genuine plaudits and widespread social media praise for a CoorDown ad is great, but if it has the side-effect of alienating parents and teachers, that has to be wrestled with. And reading poems about parenting is a totally valid approach, but if banks and detergents are doing similar things, maybe you need to find another way to stand out.

I spent the early years of my career working mainly for charities—writing for the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, Amnesty International, WhizzKidz, Ramblers Association, Alzheimer’s Society and more. While there were some ventures into radio and television, it was mainly a succession of long direct mail pieces, where every element could be tested and tracked. Changing the envelope line might increase response by 0.4%. A more creative ‘lift element’ (the leaflet or card that goes with the letter) might increase response by 4%. Even many years later, I look back on it as some of the hardest work I’ve done in my career, because there were so many sensitivities to keep in mind, and there was always this tough trade-off between cutting through to get people’s attention vs responsibly representing the issues at hand—especially with highly engaged existing supporters watching closely for missteps or overclaims.

In more recent years, I’ve ended up doing a lot of work for non-profits at the higher level of branding and messaging, often working alongside branding agencies who are specialists in those areas. The whole thing has given me great respect for what a specialism it can be. For ad agencies more used to working with commercial clients, the charity brief can strike them as unusually moving and inspiring. But for agencies who do it day in, day out, it’s not really about emoting or feeling inspired: it’s about the tough business of competing in a ‘market’ where many charities are engaged in competition for attention, support and social change in specific directions.

I’m not saying you have to be a specialist to do this stuff—there is a great history of ad agencies doing spectacular work for charitable causes. But it does involve a different mindset to the purpose playbook. Inspirational, in-your-face ads may sometimes be the answer, but they need to be balanced with sensitivity to the audiences who need to be engaged.

For all that, there is a positive message here. If one after-effect of the receding purpose tide is that ad agencies turn their attention to charities, that can be a great thing when done with skill and sensitivity. And if deodorants, chocolate bars and banks can stop sucking the oxygen out of the charity room, that will be a great thing for society.

Next post, hopefully sooner rather than later: The Road to Hell and how to pre-order it. Please give generously.

Thanks for reading. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, books about design, and occasional songs. My book The Road to Hell will be coming out in April.

Hi there Nick! Great to meet you at Circling the Square Mile recently.

WRT to charity advertising - the aphorisms developed by my grandpa Harold Sumption still hold up: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Sumption

Nice alt text.