Truthiness isn't beauty

An extract from my new book The Road to Hell, in which I examine the case of Dove, hailed as the exemplar of purposeful marketing, but based on questionable truths with doubtful effects.

This is an extract from The Road to Hell: How purposeful business leads to bad marketing and a worse world. And how human creativity is the way out. It tackles the case of Dove, frequently cited as the stand-out example of purpose marketing.

If you live in that fabled land outside the marketing industry, you might loosely associate Dove with moisturising soap, roll-on deodorants and ads that use white space a lot. But within adland, Dove enjoys an elevated status as one of the trailblazers of the purpose movement. Having been a solid part of Unilever’s portfolio since 1957, the brand sought to broaden from soap to the wider beauty category by launching the Campaign for Real Beauty in 2004, consisting of both the Real Beauty Pledge and the parallel Self-Esteem Project. Since then, it has associated itself with a social mission to “make beauty a source of confidence, not anxiety”.

One of the instigators was chief creative officer Joah Santos, who applied a method he described as POV: Purpose, Objective, Vision. From the beginning, Dove was astute enough to add a gloss of science to its social mission, commissioning a white paper with named contributors including Dr. Nancy Etcoff of Harvard University, Dr. Susie Orbach of London School of Economics, and Dr. Jennifer Scott and Heidi D’Agostino, from StrategyOne, a subsidiary of Edelman Public Relations.

Although the white paper has the air of social science, it is primarily a market research exercise conducted by StrategyOne, designed to prove the existence of the societal problem that Dove would build its brand around solving. The report opens with a quote from Keats: “‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’—that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Cultural historians will note that the word ‘truth’ was going through an interesting evolution around this time. Over the next two years, both the American Dialect Society and Merriam-Webster would make ‘truthiness’ their word of the year: the quality of seeming or being felt to be true, based on emotions rather than evidence.

The white paper involved a survey of 3,200 women aged 18-64. The headline was that only 2% considered themselves ‘beautiful’ (revised to 4% in a follow-up 2011 study). This provided the shocking figure that justified Dove’s campaign to bolster women’s self-esteem. Less reported was the finding that 72% of women said they rated their beauty as average, and only 13% saw themselves as less beautiful or physically attractive than others. It’s also worth noting that an obvious response bias creeps into the framing of questions like these. Is any of it really a finding about the participants’ inherent insecurity, or more a wish not to appear vain when being asked about their appearance?

The research would later be dramatised in a #ChooseBeautiful campaign, in which adjacent entrances in public spaces were labelled ‘Beautiful’ and ‘Average’. The resulting brand film framed the exercise as a pop science experiment, in which under-confident women chose mainly to go through the ‘Average’ entrance, barring a few who chose ‘Beautiful’ because they were sufficiently empowered, or because their mother was with them and insisted they walk through it—all to a background of swelling piano music. Again, the fact that this is a forced choice taking place in a highly public space might make it evidence of socially acceptable modesty rather than inner self-loathing. Kat Gordon, founder of the 3% Conference, which advocates more female leadership in advertising, called the campaign “heavy-handed and manipulative”. Arwa Mahdawi wrote in the Guardian that Dove “has mastered the art of passing off somewhat passive-aggressive and patronising advertising as super-empowering, ultra PR-able social commentary”.

In this case, at least women were making their own self-assessment. Dove’s Real Beauty campaign had begun with billboard portraits of what were described as regular women rather than professional models. The campaign included an interactive Times Square billboard that invited passers-by to vote on whether a particular model was ‘Fat or Fab’ or ‘Wrinkled or Wonderful’, with the results dynamically updated and displayed on the billboard. It’s reported that ‘fat’ overtook the ‘fab’ number—an early example of the dangers of crowdsourced marketing.

This public rating of physical appearance didn’t seem likely to boost self-esteem, and soon Dove learned to be more subtle. ‘Tested on Real Curves’ was a poster campaign featuring a range of ‘real’ women unlike the usual models seen in ad campaigns. It was nevertheless a curated sample. Writing in The Atlantic in 2007, Virginia Postrel noted that, “The ‘real women’ pictured in the thigh-cream billboards may not have looked like supermodels, but they were all young, with symmetrical faces, feminine features, great skin, white teeth, and hourglass shapes. Even the most zaftig had relatively flat stomachs and clearly defined waists. These pretty women were not a random sample of the population. Dove diversified the portrait of beauty without abandoning the concept altogether.”

There was a lively row when photo retoucher Pascal Dangin told the New Yorker that he had made extensive edits to the campaign photos: “Do you know how much retouching was on that? But it was great to do, a challenge, to keep everyone’s skin and faces showing the mileage but not looking unattractive.” After that inadvertent moment of candour, he later appeared to row back the claims.

The campaign received criticism for the way its stance conflicted with other brands in the Unilever stable. While Dove talked about women’s self-esteem, Axe (also known as Lynx) continued to run campaigns based on stereotypically sexualised women, while other products included SlimFast diet bars and Fair & Lovely, a controversial skin-lightening product marketed primarily in India—now rebranded as Glow & Lovely with previous references to ‘whitening’ removed from the language.

The high point in Dove’s campaign came with Real Beauty Sketches in 2013. Based on Joah Santos’s strategy and credited to Portuguese copywriter Hugo Veiga, the film would become one of the most viral of the decade, setting the template for similar ads to follow. The choreography is always similar, with nervous participants walking into a cavernous space to take part in a social experiment orchestrated by the wise and all-seeing brand. In this case, the room contained Gil Zamora, a male forensic artist from the San Jose Police Department. Placed behind a screen, the women were asked to describe their facial appearance to the artist. They reply in mainly self-effacing terms. “Tell me about your chin,’” says the man. “It kind of protrudes a little bit,” says the woman. “Your jaw?” says the man. “My mom told me I had a big jaw,” says the woman. We hear this over soft piano music—these ads would always land differently without it.

Afterwards, another stranger, who has met the participants only briefly, walks in and gives an alternative description of them to the sketch artist, this time in more flattering terms. “Her chin? It was a nice, thin chin,” says the stranger. “Cute nose,” says another stranger. “She had nice eyes, they lit up when she spoke,” says another stranger.

As the piano music swells, the original women are led back in and shown one sketch based on their own description (somewhat dour and plain-looking), then another based on the stranger’s description (comparatively brighter and more flattering). Learning their lesson, the women tear up and realise how much they’ve been talking themselves down. “Do you think you’re more beautiful than you say?” asks the male artist. “Yeah… Yes.” says the woman hesitantly, continuing: “I should be more grateful.” Another participant is shown hugging her boyfriend, having realised how unnecessarily insecure she was. “You are more beautiful than you think,” says the endline as the Dove logo appears.

The film was a social media hit, expertly framed to generate an emotional response. But some commentators were concerned. “These ads still uphold the notion that, when it comes to evaluating ourselves and other women, beauty is paramount,” wrote Ann Friedman in The Cut. “The goal shouldn’t be to get women to focus on how we are all gorgeous in our own way. It should be to get women to do for ourselves what we wish the broader culture would do: judge each other based on intelligence and wit and ethical sensibility, not just our faces and bodies.” The criticism chimes with another underreported finding in the original Dove research, which was that “beauty and physical appearance are not the primary drivers of women’s well-being”—coming behind factors such as family, friends, health, religious faith and professional success.

All this delivered undoubted commercial benefits for the brand. Ranked top in Ad Age’s list of Campaigns of the Century, the work has been credited with raising sales from $2.5 billion to $4 billion over ten years. Marketing commentator Mark Ritson has pointed out how the purposeful ads ran in parallel with many far more traditional product-centric ads—what the Dove team called their ‘dual communications model’—so it’s hard to separate out the impact of the two. Nevertheless, the purposeful ads have to be credited with raising the salience of the brand, despite (or perhaps because of) the attendant controversies.

The question for this chapter, and for anyone interested in social impact beyond commercial sales, is whether this has delivered anything good for society. As always, that’s harder to measure. One advantage of a societal mission is that it’s hard to attribute blame to a soap brand if trends go in the wrong direction (which can be framed as all the more reason to fight the good fight), but easier to claim a share of credit if things improve.

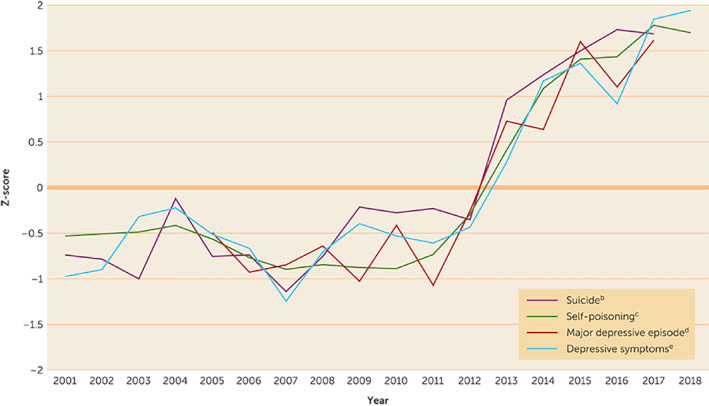

The evidence from the last two decades has not been encouraging. Figures presented in a District of Columbia filing against Meta and Instagram show an alarming rise in suicide rates among 12-14 year old girls, self-poisoning among 13-15 year old girls, major depressive episodes in 14-15 year old girls, and depressive symptoms among eighth-grade girls over the course of 2001 to 2018. There is a particular spike around 2004, then a dramatic rise from 2011 onwards, which the filing describes as attributable to the rise of mobile phones and social media.

None of this bodes well for the success of the Self-Esteem Project, but Dove’s more recent work has turned this into fertile ground. On TikTok, a #TurnYourBack campaign rails against beautifying filters on the platform. It’s a worthy target, but the campaign takes the familiar purpose approach of funding the platform it criticises. A ‘principle isn’t a principle until it costs you something’ approach might involve brands withdrawing from a platform that policy makers have discussed banning in the west. But commercial incentives mean the ‘do well by doing good’ approach is always more appealing: keep advertising to a key demographic, but frame it as resistance.

Social media spend has risen accordingly. At the start of 2023, marketing insight organisation WARC upgraded its ad spend forecast for TikTok by almost $2bn to $15.2bn, noting that 75% of marketers planned to increase their activity on the platform: a 52% increase in ad revenue over the previous year. If social media platforms are largely to blame for the mental health crisis, it may be due to the ad-funded model that incentivises clickbait, confrontation and controversy. Without the ads, there would be fewer problems for Dove to solve, or for other brands to ‘lead the conversation’ about.

Psychologists might ask other questions about the Dove approach. There’s a well-known joke about how to make someone feel insecure: just go up to them and say “Look, whatever anyone else is saying, I think you’re amazing.” While it’s framed as an empowering compliment, most people’s natural reaction will be: “Wait, what is everyone else saying?”

You could say this has been Dove’s brand strategy for 20 years. As I wrote in my first article about purpose in 2017, “Advertisers reinforce the insecurities they claim to fight, and introduce new insecurities that people didn’t know they were supposed to have.”

Writer and comedian Mindy Kaling has written about the wave of ‘empowerment’ advertising aimed at women, with Dove at the forefront.

“We just assume boys will be confident, like how your parents assume you will brush your teeth every morning without checking in on you in the bathroom. With girls, that assumption flies out the window. Suddenly, your parents are standing in the bathroom with you, watching you brush your teeth with encouraging, worried expressions on their faces. Sweetheart, you can do it! We know it’s hard to brush your teeth! We love you! Which must make girls think, Yikes. Is brushing your teeth a really hard and scary thing to do? I thought it was just putting toothpaste on a toothbrush. I get worried that telling girls how difficult it is to be confident implies a tacit expectation that girls won’t be able to do it.

“The good news is that, as a country, we are all about telling girls to be confident. It’s our new national pastime. Every day I see Twitter posts, Instagram campaigns, and hashtags that say things like ‘We Will!’ or ‘Girls Can!’ or ‘Me Must, I Too!’ on them. I think widespread, online displays of female self-confidence are good for people, especially men, to see. I just sometimes get the sneaking suspicion that corporations are co-opting ‘girl confidence’ language to rally girls into buying body wash. Be careful.”

‘Be careful’ continues to be good advice. In another Dove brand film, called Toxic Influence, mothers and daughters are led into the familiar cavernous space to talk to the all-powerful voice of Dove. Speaking from somewhere off-camera, the voice asks the mothers and daughters to discuss the effects of phone use and social media, to which the mothers give superficially complacent ‘It’s fine’ answers. Dove then shows the participants a film in which deepfake technology has been used (apparently without permission) to put toxic beauty advice into the mouths of the mothers, who eagerly advise their daughters to use Botox, try powdered diet foods (maybe SlimFast) and file their teeth with a nail file. “That is not me!” cries one shocked mother.

“You wouldn’t say that to your daughter,” admonishes the brand. “But she still hears it online, every day.” The mothers are tearful. “A girl’s greatest influence will always be her parents,” reads the message on the big screen. “Always be talking” is the lesson they learn.

One day it would be interesting to run another kind of pop science experiment. Nervous Dove marketers could be led into a cavernous space and placed in front of a giant screen. The screen could show the mothers from the Toxic Influence ad saying ‘Wait, so who funds these platforms?’. The piano could come in as a headline shows Unilever boosting its 2023 marketing spend by €500 million and opening 29 new digital marketing, media and ecommerce hubs. The strings could swell as a caption appears: “Today, women are three times more likely than men to experience common mental health problems. In 1993, they were twice as likely.” A marketer could shed a tear as the Dove logo fades from a Covid nurse’s face and an NHS logo appears in its place. A marketer’s boyfriend could give her a hug as Radhika Parameswaran, professor of gender and media studies at Indiana University Bloomington, relates how Fair & Lovely holds a 70% share of India’s skin-lightening market and “Just removing the word ‘fair’ is not enough.” Another marketer might murmur “I should be more grateful” as he reads about Unilever’s profit margins on the back of price rises during the cost of living crisis. The music could reach a crescendo as a group of Ukrainian amputees emerges from behind the screen and explains how Unilever doubled profits to 9.2 billion roubles and increased ad spend by 10% to 21.7 billion roubles after the Russian invasion. Then the endline could appear: “But $2.5 billion to $4 billion in sales, so it’s all good.”

Harsh, maybe. But these are the conversations that purpose invites. Dove deserves praise for running a successful commercial campaign and smartly riding the cultural waves of the past two decades. But the purpose of purpose is purpose, and the impact of a social intervention has to be measured by its social outcomes. In that context, it’s not enough to talk about starting conversations or generating social media impressions. When it comes to social impact, the warm feeling you get at the end of a Dove film is an unreliable guide. Truthiness isn’t the same as truth.

Thank you for reading. Please buy the book! And a quick rating and/or review on Amazon is a great help. Hoping to have a Kindle version out soon (but please buy a hard copy anyway).

Great peek into the book, which is on the Christmas list!

Really enjoyed this! Thank you. Hopefully will be able to get a copy of your book down here in SA.