The Road to Hell, part 2 of 3

The second part of my not-very-concise case against corporate purpose, covering how it leads to worse marketing, and how it leads to worse social outcomes.

Hello again. In part one, I covered what purpose is and where it came from. In this post, I’ll set out how it leads to worse marketing and worse social outcomes. (I’ve made some of these arguments in more depth elsewhere, so follow the links or check the archive for more.) The image above is from Left-Handed Mango Chutney, which I mention further down.

How does purpose lead to worse marketing?

One difference between me and other purpose sceptics is that I’m not primarily interested in whether it works marketing-wise. I don’t think it does, but I’d almost be more worried if it did—because it’s the social outcomes that are the real problem. Equally, I believe any campaign that claims the mantle of ‘purpose’ should be judged by social outcomes, not commercial metrics. That ought to be obvious ethically, but it’s surprising how often it’s forgotten.

It’s also worth noting that the case against purpose as a marketing tool should ideally come after someone has made a decent case for it. And even 15 years into the movement, no one has. One of the most influential texts was Jim Stengel’s Grow (2011), in which he cited 50 brands that he claimed were evidence of purpose working. The web of post-rationalisation, selection bias and wishful thinking was comprehensively dismantled by Richard Shotton. But a version of Brandolini’s Law applies in these cases: the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it. For all the good work of Shotton and others, the meme of purpose was already spreading to boardrooms around the world, no doubt helped by a credulous cover quote on Stengel’s book from Martin Sorrell, about which he should be embarrassed. For my part, I invested some energy in deconstructing a more recent attempt to justify purpose by the IPA—you can read that one here.

For now, I’ll cite three reasons why purpose may not inevitably lead to commercially ineffective marketing, but certainly increases the probability of commercially ineffective marketing.

First, it leads to sameness.

This is a problem when the point of marketing is to create difference or distinctiveness.

A structural flaw with purpose is that it turns every brand into a slightly different version of ‘We’re here to make the world a better place’.

You can see it in the language of some of the most prominent brands of the 2010s. Unlocking the potential of human creativity… giving people the power the build community… elevating the world’s consciousness… It’s all highly abstract and grandiose. Purpose compels you to climb the ladder of abstraction until the day-to-day reality of your business becomes a speck in the distance.

The ascent is always similar. You start with saying, ok, we exist to make widgets. But in a way, aren’t those widgets about making some mundane task slightly easier? And doesn’t making it slightly easier make people’s lives slightly better? And we want to sell our widgets to everyone, so in a way… our purpose is to make life better for everyone, everywhere! There are variations on this—maybe your widgets are slightly cheaper, in which case you can talk about democratising the widgets. Or they exist in a market that connects to a social issue much broader than your brand, in which case you could lead a conversation that lends your widgets some spurious borrowed interest.

In all cases, the language becomes more abstract as you move away from the widget. And while the logic sounds passably plausible in one direction, it evaporates when you try to trace it in reverse. If you were truly creating an organisation whose ‘reason for being’ was to unlock the potential of human creativity, you wouldn’t end up with a proprietary music platform based on micro-payments to struggling musicians. The purpose is a just-so story that is retrofitted to the business later, and the clue is often in the name—Airbnb didn’t start with why, it started with airbeds and breakfast. Facebook didn’t start as a way to build community, it was a creepy way to rate the hotness of fellow students.

In the end, you look at all these brand statements alongside each other and get precious little sense of these being different businesses doing different things in the world. Maybe the trend towards flat logos is related to this conceptual flattening out, placing all brands on the same abstract plane of whyness.

Second, purpose builds your brand on a weak foundation.

I’ll make this point using Hellmann’s, though some may bring forth metrics to say it’s been a commercial success. Whether or not that’s true, I don’t believe purpose plays any role on the upside.

Hellmann’s is a brand that has existed for 110 years, but only recently discovered that its purpose is to reduce food waste, supposedly by helping to use up leftover food in your fridge.

This repositioning came in for criticism from Unilever investor Terry Smith, who said “A company which feels it has to define the purpose of Hellmann’s mayonnaise has, in our view, clearly lost the plot.” It was one of several developments that has led to a repositioning at Unilever, with CEO Alan Jope set to depart, and murmurings about maybe having overdone the purpose thing.

In some ways, I’d be kinder than Terry Smith. I don’t think it’s a totally unbelievable claim to say Hellmann’s could play a role in reducing food waste. But I think most everyday punters would agree it’s… a bit of a stretch. After all, you could equally argue that mayonnaise simply adds to food waste—another item gradually turning yellow in the back of your fridge. Maybe eggs are the real heroes in this, helping to use up your leftover Hellmann’s.

The whole thing led to a weird Super Bowl ad, in which Jon Hamm and Brie Larsson played the roles of ham and brie in Pete Davidson’s fridge. There was a valiant attempt to do it with humour, but I felt sorry for the creatives involved, because you’re fundamentally starting from an overclaim and straining to make it work.

Of course, many brands build themselves on an overclaim—we’re the world’s favourite airline, we’re probably the best lager in the world. But it’s one thing to exaggerate about your product. It’s another thing to make an exaggerated moral or ethical claim—and that’s what purpose tempts you to do. Purely from a PR perspective, it sets up a precarious pride-before-fall narrative that creates a harsher backlash when you’re inevitably caught doing something less than perfect.

Thirdly, purpose centres the brand, not the customer.

And this is one of the cardinal sins of branding.

If you’ve ever read The Copy Book—a collection of work by advertising copywriters—you’ll notice a recurring theme in the interviews. Good writing comes from focusing on the reader, not the brand. Mary Wear says “Know your target audience. Not intellectually, but intuitively. Think like them, empathise with them, identify with them”. John Salmon says “You should write from the standpoint of the reader’s self-interest”. Steve Harrison says “Read your copy and check that ‘you’ appears three times more than ‘I’ or ‘we’. This helps you write about the subject from the reader’s perspective”.

Purpose pushes you in the opposite direction. The language is all We believe that… Our values are… We’re leading the conversation… Our founders were sat around the kitchen table…We’re democratising… We’re starting a movement.

And it’s not just the language: it’s a deeper point about the mindset of marketing departments. Many companies have spent the past decade studying their own navels, trying to find anything resembling a purpose. It’s been a huge waste of intellectual energy, if you can dignify it with that term. Brands would gain more from forgetting about their ‘why’ and looking outwards to the world. It’s full of customers who have their own perspectives. Think about them, not you. Even the marketers at Hellmann’s only got into the rarefied position of pondering their ‘purpose’ on the back of decades of hard-working creative advertising that is 98% of the reason why any of their purpose ads get noticed today—and 100% of the reason why they have the budget for those Super Bowl spots.

How does it leads to worse social outcomes?

So if that’s how purpose leads to worse marketing, how does it lead to worse social outcomes? Again, I’ll cite three reasons. And the first is this:

It leads to worse marketing.

In most cases, that’s a bad thing in itself. There are millions of decent business owners doing their best to make a living for themselves, their employees and their employees’ families and communities. Bad marketing is bad for them. It’s a point that shouldn’t need emphasising, but many marketers now find it fashionable to doubt the benefits of markets in general. It’s possible to believe in alternatives, but the marketing industry is a strange place from which to do it.

But marketing isn’t just about shifting product. It’s also a form of culture and entertainment, from which no one can opt out. We force people to watch ads before the latest episode of Succession, and we erect giant billboards for them to encounter on their way to work. When you invite yourselves into people’s lives like that, there’s a responsibility to make something good. Something that respects people, entertains them and charms them, as opposed to something that preaches, bores and talks down to them.

As I’ve written before, people used to laugh at ads, now they laugh at ad agencies. There are many brilliant parodies (including Left-Handed Mango Chutney) where the creators have picked up on the earnest over-claims and ridiculous grandstanding of contemporary advertising. And don’t kid yourself that this is all about Kendall Jenner and Pepsi—that was 2017. Outside the Dove soap bubble of advertising, most of the world doesn’t regard its body wash as a moral hero, and most punters recognise that the Goldman Sachs bros wearing their Patagonia gilets aren’t buying them to save the planet. People sense when they are being played by brands, and advertisers should sense the mood of the people.

Secondly, purpose leads to noble cause corruption.

Moving away from marketing, purpose is a dangerous ethical compass for businesses, because it leads to a feature of behavioural psychology known as noble cause corruption. If you convince yourself as a human, and certainly as a business, that you exist in service of noble goal, it can paradoxically make you more likely to justify any means towards that end. After all, you’re one of the good guys. And if you’re doing well, you have even more chance to do good. Maybe it’s OK to cut a few corners.

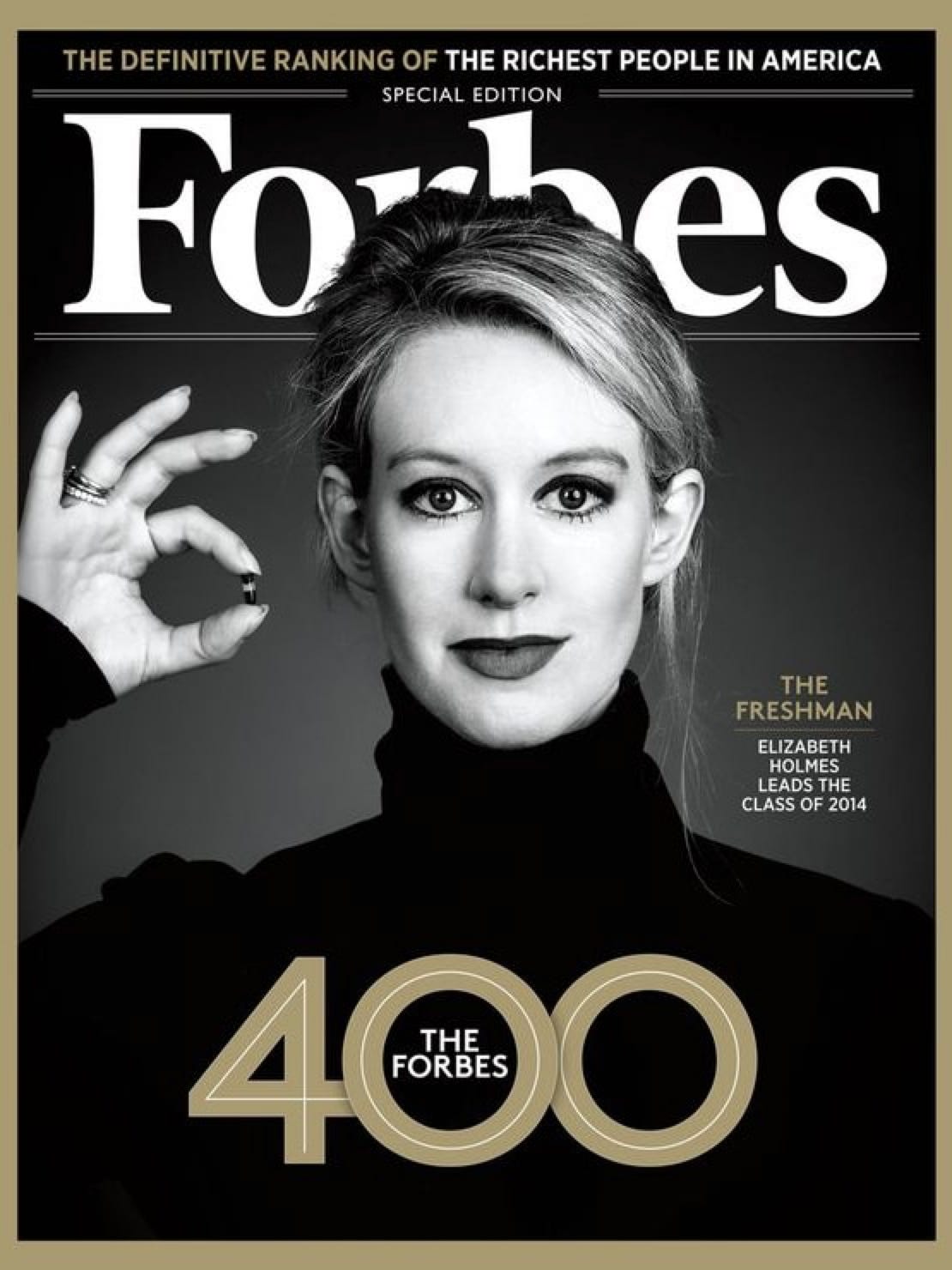

This leads to dark places. One case study is Elizabeth Holmes, now beginning an 11-year jail term in the US. (Her former partner Sunny Balwani is already serving 13 years.) Not so long ago, she was shaking hands with presidents, hailed as the next Steve Jobs, and leading a business valued at over $9 billion.

That business was Theranos, a Silicon Valley start-up that claimed to be developing a finger-prick blood test which could detect many diseases and conditions from a single drop of blood. The problem was that the technology never existed: a truth that eventually became undeniable, despite years of hostility towards any ‘cynic’ who dared question the lofty narrative.

Journalist John Carreyrou knows the story better than most, and the first chapter in his book is titled ‘A Purposeful Life’. It’s clear that purpose played a significant role in Elizabeth Holmes’s psyche. To this day, it’s unclear how much she believed in the story she told. She appears to be a victim of noble cause corruption, and the same moral self-delusion plays out in less dramatic ways in boardrooms around the world.

Thirdly, purpose undermines the public and non-profit sectors.

This is the most important point, and I’ll make it by talking about Cadbury’s.

I pick this example because it’s one of the strongest cases on the purpose side of the debate. Last year, it won the ‘social purpose’ category of the IPA Effectiveness Awards, as well as the overall Best in Show.

With the usual caveats about IPA awards only measuring whatever data the clients and agencies are happy to share, Cadbury’s was an impressive campaign. The case study boasts some strong commercial metrics (jarringly set alongside images of sad-looking kids from the ads). But there is nothing about the social outcomes of this supposedly socially purposeful campaign.

When you dig into the details, you eventually find mention of a charity called Age UK, which does valuable work to combat loneliness among older people. It turns out Cadbury’s has donated some profits from the campaign towards this charity, all of which is laudable but nothing new. Companies have long donated to charities—it’s one of the more useful things businesses do. What is new is the way purpose encourages companies to make themselves the centre of the story, while the charity (the actually socially purposeful organisation) is relegated to the small print. There was a time when it was considered graceless to donate to charity and be extremely vocal about it. Now companies go much further, using the donation as the premise for constructing their entire, lucrative brand image.

According to Cadbury’s, it’s also more than a brand image. The senior marketing director behind the campaign is quoted as saying: “Aligning Cadbury’s behind a clear brand purpose—generous instinct—has been transformative for our brand. It’s given the team a north star to guide our decisions.”

Is it cynical to wonder where this north star was during the years of paying zero tax on hundreds of millions in profits, as was widely reported in the UK? Or is it cynical not to? Paying tax might be the single most socially purposeful any business can do—it’s an excellent way to fund schools, hospitals, public transport and services for the elderly. Maybe it’s legally defensible to use clever accounting tricks to avoid it, but basing your next marketing campaign on generosity ought to get you chased from the room, not applauded onto the awards stage.

And there’s another twist. In recent years, Cadbury’s has existed in an increasingly uncomfortable environment when it comes to HFSS (high in fat, salt and sugar) advertising regulations. I don’t have a strong opinion on the rights or wrongs of the regulations themselves—I like Dairy Milk and don’t see much problem with advertising it widely. But the bigger point is that, as a democratic society, with cross-party support, we’ve decided that we want to see less of this kind of advertising, because we think it would be socially beneficial if fewer of these products were sold.

Whatever your view on purpose, the disconnect should be painfully clear. As an ad industry, we hail Cadbury’s not just as a successful commercial campaign, but as the social purpose campaign of the year. And everyone involved goes away feeling reassured about the socially positive contribution of our industry. Meanwhile, out there in society, people are specifically asking for less of this kind of advertising, and wondering if it’s OK for Cadbury’s to pay more tax in future.

This is just one story, but it’s indicative of how purpose acts as a giant distraction from any sober consideration of actual social purpose, which exists primarily in the not-for-profit and public sectors. In saying this, I’m not setting up a simple distinction of corporate = bad and public/non-profit = good. There are plenty of problems in all these sectors. But there is a higher logic in recognising the distinctness of these spheres in society, even as they continually interact and play off each other. The past decade has seen a bloated corporate sphere encroaching on areas far beyond itself, often posing as the solution to problems that business itself has caused.

More on that in the next post.

Thanks for reading. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, books about design, and occasional songs. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Your ability to engage with “purpose” as a topic worthy of more than scorn is honestly impressive. Really enjoying the series.

Are people getting paid to mention Suck Session here? I hate it and I've never seen it.. and I never want to. lol. And I ONLY ever see it mentioned here, for some reason.