The post-purpose election

If the 2007-2008 financial crisis marked the start of the purpose era, the 2024 election might just mark its end.

It’s been a strange 15 years.

Consider the picture on the left—a poster advertising the Occupy Wall Street protest of 2011. ‘What is our one demand?’ the poster asked, coming in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis and the anti-corporate feeling it generated. ‘Representation not corporation!’ came the reply from supporters. Framed as the 99% against the 1%, Occupy Wall Street aimed to separate big money from politics, push back an encroaching oligarchy, and revive grassroots democracy.

Next, consider the middle picture. By 2017, the protestors had disappeared from Wall Street, and in their place came Fearless Girl—a symbol of youthful, feminist protest, but not one that came from an upstart guerrilla movement. Instead, the statue was the brainchild of ad agency McCann, working on behalf of asset management firm State Street—one of the targets of the 2011 protests, now warmly applauded for its progressive stance. Even as it collected 18 Cannes Grand Prix awards and two D&AD Black Pencils, State Street was quietly reaching a $5m out-of-court settlement with its black and female employees over claims of historic underpayment, and subsequently became embroiled in a years-long battle with the female sculptor over her intellectual property rights. But the statue hit the zeitgeist. It was the embodiment of a purpose movement that had risen since 2009, reframing business as the progressive left’s most powerful ally. ‘Representation not corporation!’ had been the demand. ‘Representation by corporation!’ was the response.

Then consider the third picture, inexpertly mocked up by me. When Donald Trump was first elected in 2016, it sent the corporate purpose movement into overdrive, as CEOs vowed to step in where political leaders had failed. Larry Fink, a former Wall Street trader who pioneered the mortgage-backed securities that eventually led to the crash, was now head of BlackRock and vowed to use his firm’s $10 trillion market power to push a social purpose agenda. The US Business Roundtable followed suit, releasing a new Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation in 2019. Purpose was in the ascendant, Biden saw off Trump, countless businesses set about making the world a better place…

… and then Trump got elected again, this time winning the popular vote and all seven swing states.

The question is—will corporate leaders ‘step up’ again, breathing new life into a purpose movement that has been flagging? Or is there already a different mood emerging, in certain sections of the left?

I’m hoping it’s the latter, and I’m going to offer five reasons why it should be.

1. The narratives aren’t working

First, it’s worth noting that this wasn’t a massive Trump landslide, and it could have gone the other way if it wasn’t for an ‘incumbent penalty’ that has hit many governing parties in post-Covid times. But the deeper question for Democrats is why it’s so close in the first place—and none of the dismissive, feel-good answers work.

For the detailed analysis, I defer to

and his Graveyard of Bad Election Narratives. He lists many confounding facts for anyone reaching for the easy identity explanations. Read the post for the full analysis and sources, but briefly:It wasn’t racism

- Trump has done worse with white voters in each successive election

- The whites who shifted most towards Democrats were white men

- Every ethnic group except for whites moved towards Trump

It wasn’t sexism

- Harris performed worse with women than any Dem candidate since Kerry in 2004

- Harris did better than Hillary with white women, and worse with black, Hispanic and Asian women

- While rejecting Harris, voters elected a record number of female governors, and the first transgender woman in US Congress

It wasn’t old people

- Voters under 44 have shifted 9 percentage points towards Trump since 2016

- Voters over 65 have shifted 7 percentage points towards the Democrats since 2016

It wasn’t billionaires

- Yes, Trump has Musk at his side

- But Harris had 60% more billionaire backers than Trump

- Dems raised twice as much as Republicans, largely through billionaires, multinational corporations, and ‘dark money’ PACs

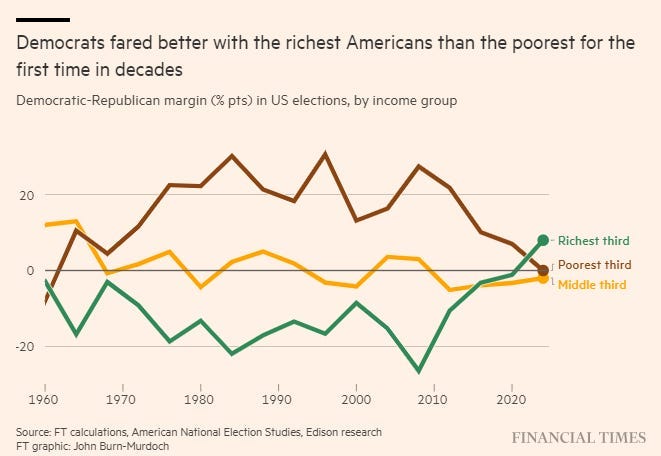

- Harris was the clear choice for voters with six-figure salaries or higher, while Trump won with people earning less than $50k per year

It wasn’t turnout

- Yes, Harris’s turnout was about 10 million voters lower than 2020

- But in all the swing states that mattered, turnout was higher than ever

2. Voter priorities don’t match corporate priorities

So what was it?

As always, election results are over-determined and there’s no single narrative to explain it all. But look at the research from Blueprint, the Democrat-supporting research group who surveyed thousands of voters immediately post-election, and the answer emerges across ethnic groups: It was a combination of inflation, immigration and alienation from cultural liberalism, or what is sometimes called ‘wokism’.

Despite how some define it (see a recent debate I attended in the House of Commons), anti-wokism in this context needn’t mean being racist, sexist or bigoted. Instead, it might mean being against any or all of defund the police, biological males in girls’ sports, open borders, the cultural norm of pronouns in bios (quietly dropped earlier this year by AOC), affirmative action, and a hardline identity essentialism that insists on shared identity meaning shared politics. This election might mark the end of the ‘demography is destiny’ mindset where all the left had to do was wait for the old white people to die, and sweep up the black, Hispanic and Asian votes that they believed were theirs by right. (For a recent example of the latter mindset in action, see the Guardian columnist calling Kemi Badenoch “white supremacy in Blackface” and part of “the Black collaborator class” for daring to be a black woman with different politics.)

If inflation, immigration and cultural liberalism are weighing on voters’ minds, how many corporations are stepping up to push that agenda? Which company’s purpose is to bring down prices? Which multinational’s purpose is to have greater controls on immigration and cheap labour? Which brand’s purpose is to focus less on the diversity of the C-suite and more on shrinking the pay ratio between its lowest paid workers and the CEO?

One problem with enlisting corporations to push a social purpose agenda is that they only push the issues that suit them, which are usually social and cultural. And as those issues grow in salience, it necessarily shifts attention from the issues voters care more about, which are usually economic.

In the wake of the election, these two graphics have been widely circulated, showing the marked shift leftwards on cultural issues since 2012, much of it coming from the ‘white progressives’ who are over-represented in marketing departments and ad agencies, and all of it tracking the post-2008 rise of corporate purpose. Marketing departments could do worse than right-click these images and select them as a screensaver for the next four years.

3. The Gen Z dream is over

‘Democrats’ Gen Z dream just died’ said Newsweek on the day after the election. The same could be said of the purpose dream pushed by Edelman, McKinsey, Deloitte, University of the Arts London (with their Chief Social Purpose Officer and Sinek-pilled Vice Chancellor), ad industry institutions, and any number of purpose-driven agencies. According to exit polls, only 42% of Gen Z voters turned out to vote at all—down from 2020. Of those, 56% of men between 18 and 29 went for Trump, along with 41% of women—up from 33% in 2020.

In the face of the most authoritative opinion poll of all—an election—it’s no longer possible for purpose advocates to claim that the purpose agenda is driven by upward pressure from an impatiently progressive generation. But it probably won’t stop them trying—look out for a wave of Gen Alpha articles in the near future. Like the millennials and Gen Z-ers before them, they’ll be billed as the new purpose generation, eerily attuned to the values of every brand they buy.

All this is a narrative to serve a business model: lull anxious, middle-aged managers into believing everything’s changing, then sell the solution from conference stages around the world, basking in the glow of goodness as you send in the invoice. Left-wing critic Anand Giridharadas described the dynamic in his 2019 book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, lamenting the culture of hollow thought leaders: “positive, unthreatening, mute about larger systems and structures, congenial to the rich, big into private problem-solving, devoted to win-wins”.

4. Brands can justify being impartial

Pick a side, silence is violence, neutrality is not an option, politics is a competitive advantage—a crucial part of the purpose narrative has always been that brands can’t stay out of politics. That would be an existential threat to the legions of consultancies and thought leaders who are highly paid to advise them on it.

But brands are getting wise to it. As can happen with any mass-market brand, McDonald’s was drawn into the US election campaign in ways that were initially beyond its control—with the Democrat National Convention making Kamala Harris’s reported time at McDonald’s a major part of its PR narrative. In response, the Trump campaign approached one of McDonald’s thousands of independent franchise operators and set up what would become a high-profile photo op, leading to an outcry from some Democrat supporters and talk of a boycott.

In response, McDonald’s could have disowned the appearance with a stern reprimand for the franchisee—the kind of panicked reaction that might have happened in 2020. Alternatively, it could have embraced Trump closer and risked a Bud Light in reverse. In this case, McDonald’s wisely did neither, staking out its neutrality in an open letter: “We are not red or blue—we are golden” was the key phrase. Corny maybe, but a deft piece of PR that other brands will have noted. (I wrote about the case for brands as common ground in this piece for MediaCat.)

Next time purpose advocates urge brands to pick a side, the advice should ring even hollower than before. It never made sense in an era when elections were being decided by close to 50-50 splits, with both sets of voters equally crucial to marketers of detergent, deodorant, beer, biscuits and just about everything else we buy. It makes even less sense in an era when brands can reasonably ask—which side? The one that won?

5. The left might realise it doesn’t like oligarchy

“The best form of government is the benevolent dictatorship. And the same is true in organisations. The whole idea of consensus is lowest common denominator. How do you please as many people as possible? You end up with something incredibly diluted. Look at any congressional bill that passes… Rare are the bills that are truly profound and great because you have to please as many people and as many constituents as possible. So a leader is the single person, or no more than a pair of people, at the top, who explains their vision of the world and asks those in their organisation who believe what they believe to help build it. Consensus is not the way. There is only one vision and there can be only one vision.”

So said purpose prophet Simon Sinek in a 2010 interview. It was meant to be an argument for businesses stepping up where politicians had failed, under the guidance of benevolent CEOs who would pursue a singular vision, cutting through the slow business of consensus.

14 years later, we have a pair of billionaires at the top who might finally give the lie to that vision. Some alliance of Hillary Clinton and Paul Polman might be what Sinek had in mind, but the same road leads inexorably to Musk and Trump. If you’re advocating for business leaders using their market power to dictate societal outcomes, you have to take the whole package.

So what next?

An alternative package is available.

I hope we’re in the early stages of a preference cascade where disillusioned people on the left, who fear they are one of the few, start to realise they’re one of the many. There are already glimmers of the economic left reasserting itself over the identity left—an outcome that could deliver most of the goals of the latter more effectively in any case. I hope there will also be glimmers of brands taking corporate ethics more seriously and themselves less seriously. I hope there will be signs of businesses embracing their limited place in society and playing that role effectively. To rehearse the advice that it’s not entirely my place to give: Listen to your customers without judgment, respect the autonomy of your employees, grow brands with creativity and cognitive empathy, build out the common ground, and generate the economic growth that will benefit every demographic—younger generations more than anyone.

And I hope the ad industry will recognise its worthwhile place in that effort—re-centring the commercial creativity at which it can still excel, without losing sight of the role creativity can play in social change, but usually when channelled through the not-for-profits, social enterprises, community organisations, governments and protest movements who can actually deliver it.

All of which brings us back to the three images at the top of the post.

The first is a ballet dancer—a symbol of grace, creativity, art, humanity, the things that transcend markets and politics.

The second is a girl in an Amy Cuddy power pose, Cuddy being one of the TED talk influencers whom Anand Giridharadas deconstructs in his book—the body language expert who purveyed the corporate-friendly idea that sexism could be addressed by women adopting a certain stance on stage and in life, rather than through a deeper structural agenda that might not get you invited to TED talks.

The third is the bullshitter atop the bull, doing a victory dance despite everything that could have stood in his way—January 6th, John McCain, Serge Kovaleski, counter-endorsements from Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Oprah Winfrey and Bruce Springsteen, four criminal cases, two assassination attempts…

This is the candidate Democrats failed to beat, and it’s where we’ve arrived after 15 years of pushing a confected idea of how businesses can best serve the world, and how social change can best be delivered. It’s not a pretty place to have ended up. But at least the road was paved with good intentions.

For anyone interested, I’ve had some good conversations on a number of podcasts lately, including:

Masters of Credibility

Unmtchd

On Strategy

The Brief Bros

Marketing Book Podcast

Fuel

In Clear Focus

WARC podcast

Teamleader

The book (including a Kindle version) is available to buy, like, review, share… all support greatly appreciated.

Spot on. I'm glad I'm not the only one who has thought this. I will be sharing. Thanks.

Brilliantly argued piece. Having worked in the creative industry for many years and latterly for a university then a philanthropy I think this hits all the marks. Purpose doesn't sit well with profit and no amount of marketing spend can dispel that. What I find fascinating is that there's a welter of evidence proving that Gen X avoid branded comms at all costs. Imagining that brands can be agents of social change for that group is at best wishful thinking and at worst wilful ignorance.