The opposite of school

On a word that has radically changed life in our household: ‘unschooling’.

Hello again. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural issues.

NB: I’ve written this alongside my wife Sue – the artistic half of Asbury & Asbury. It involves sharing more about our family life than we’d normally like, but it touches on such an important subject that it feels worthwhile.

Our only child R. is ten years old and doesn’t go to school. Nor is he being home-schooled.

As of April 2021, when he left school for good, R. gets up every day and does whatever he likes, nearly all of which currently involves a screen and Minecraft and YouTube. We don’t plan on him ever going to school again, but he knows it’s an option, as is higher education in future if he is inclined.

Together, we are pursuing something known as ‘unschooling’: the practice of unplugging from a school system that wasn’t working and relearning how to follow your innate interests and instincts. Originally coined in the 1960s, unschooling has become the default word for this way of life, because it’s short, memorable and emphasises the difference from conventional schooling. But a more easily understood term is ‘self-directed learning’. Either way, our role as parents is to be creative facilitators and not to freak out every day because he doesn’t go to school and does what he likes all day!!

If you’d described this scenario to me and Sue ten years ago, we would have thought it was a wildly unlikely fiction, possibly involving a collective mental breakdown. We are not alternative lifestylers by nature and think of ourselves as pragmatists in most areas of life. But it’s come about through a convergence of two forces: a push factor and a more recent pull factor.

The push factor

It’s part of the story, but certainly not all of it, to mention that R. has a diagnosis of autism, which he received at the age of 7. This itself was the end of a long journey that began at the age of 18 months, when Sue first began to put the pieces together. (I was slower on the uptake.) At the time of the diagnosis, we were told what we already knew: that school would be a bumpy ride and our best hope was to ‘muddle through’.

We muddled as hard as we could, always straining to stay on good terms with the school, even as we managed years of decline and marginalisation. R. was bright enough, a keen reader early on, good head for maths, and a standard obsession with football, coupled with an inability to play as well as he’d like – dyspraxia and the resulting physical clumsiness being part of his challenges. Contrary to the clichés around autism, he wasn’t a self-contained loner with an unusually precocious skill in a certain area. He craved ordinary social contact and status, but found it impossible to navigate that world successfully.

Gradually, a curious and fun toddler was reduced to a ‘problem’ 10-year-old, suffering repeated social humiliations and a sense of mounting injustice, as he was cast as the cause of situations he was desperately trying to avoid. He came out the classroom door on most days looking dead-eyed and drained. Many of his social difficulties involved children with challenges of their own, all of them struggling to navigate this strange schooling system we have inherited from relatively recent history.

There were great teachers alongside the judgmental ones, and usually enough glimmers of hope to think things might turn around. We saw our role being to hang in there, smooth the way as best we could, and hope that secondary school would be better – a chance to find his tribe. We dealt with SENCO, EHCPs, and that whole system of acronyms and paperwork that is set up to deal with children who have what are termed special needs. But the end goal was never that enticing: at best some additional one-to-one support to help him fit in, mainly in the sense of making him less distracting to those around him.

For us, lockdown came as a relief – no more dealing with the daily battles and entire evenings trying to get back to equilibrium. But it also showed us that conventional home-schooling wouldn’t work either, confirming how R.’s ‘demand avoidance’ was as intractable as any trait you can imagine. It had been there all his life and we had done all the usual parenting things to try to manage it. It was never really a spoilt, foot-stamping refusal to do things, but a simple inability to respond to the subtlest of demands, even though he generally liked approval and being thought of as ‘good’.

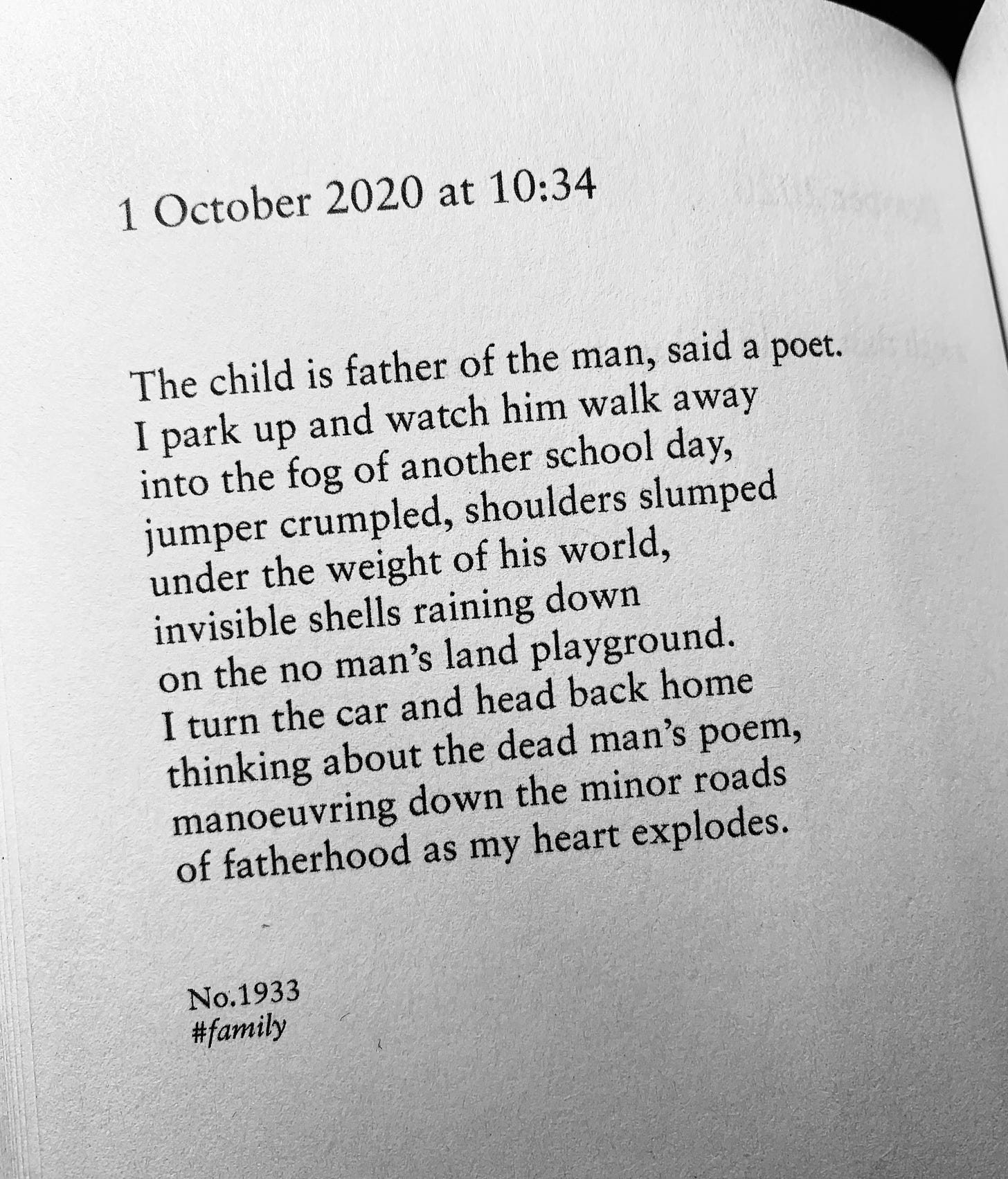

The transition back to school in autumn 2020 was disastrous and the beginning of the end. To convey the mood of those last days, I could show you this poem – one of the rough, diary-like poems that I wrote as part of Realtime Notes, composed just after the morning school run.

Or I could point you to the painting by Sue at the top of this post, which is titled Square Peg. It was painted in spring 2021, during the last fraught days of straining to keep R. in the school system. Shortly afterwards, at the end of spring term, we withdrew him from school, initially with the intention of trying another, much smaller, local school. But during the Easter holidays, we mustered the courage and clarity of mind to pursue what we knew to be the only truly positive option: to withdraw him from school altogether.

That decision was helped by a significant pull factor, which came in the form of a book.

The pull factor

Being a writer, I’m supposed to believe in the power of books to change your life. But I’ve never had a good answer to the question of which book has changed mine.

Now I do: Changing Our Minds by Naomi Fisher.

It landed with helpful timing, in spring of 2021. Sue and I had already come across many books about education, autism and schooling. Sometimes you see yet another title and assume it’ll be some happy-clappy life advice that worked for one person and no one else. But something about the blurb spoke to our situation and we impulsively ordered it. A few days later, the book landed and we each consumed it in a couple of sittings.

The book had immediate relevance in our case, but it’s also a great read for the generalist: sharply written and perceptively argued, in a way that pre-emptively answers the objections that arise in your head. It may make you think differently about your own school experience. Most of us have spent about 20,000 hours of our lives in school, so we all have some insight to bring to the topic.

Briefly, the book’s argument is that we are socialised into thinking that schooling is synonymous with education. But it’s really only one way to learn. Self-directed education is not only a better alternative for some children, but the only humane option that doesn’t cause lasting damage.

On one level, it’s not that radical an idea. Self-directed education means learning by following your intrinsic motivation, rather than demands imposed on you from outside. Adults do it all the time: it’s how Sue became an artist. So do most children from the ages of 0 to 4. At that age, children absorb an astonishing amount of information about how to process language and interact with the world. But from the ages of 4 to 16, a different system takes over: one in which children are expected to learn the same things at the same rate, and are gradually organised into relative successes and failures on the basis of how they perform in tests.

The book goes into fascinating detail about the assumptions that underlie this system, which evolved mainly to meet the logistical challenges of managing large groups. Self-directed learning isn’t a new alternative. I was pleased to discover that Leo Tolstoy was an early advocate, setting up a voluntary school for peasant children on his estate, where learning revolved around the interests of each child.

But rather than rehearse the full argument of the book, I will skip to the happy outcome for us: a conviction that self-directed learning or ‘unschooling’ represented a truly hopeful alternative to the otherwise grim prospect of muddling through.

Dropping in

We’re currently six months into a process known as ‘deschooling’ – an extended period of decompression from six years of school, and a necessary transition for the parents as much as the child. It’s both an unsettling and liberating experience to detach yourself from the rhythms and expectations of school, and begin thinking of the future as truly open-ended.

One of the maxims of unschooling is to think of it not as ‘dropping out’ of school, but as ‘dropping into’ a new world. And there is a big world into which to drop. Sue and I continue to fall down various rabbit holes of information: books, podcasts, Facebook groups and Twitter threads. While we’re not inclined to wear ‘unschooler’ as a badge of identity – it’s something we do, rather than something we are – we inevitably feel some kinship when it crops up in random news articles. Oh look, Paul Weller is unschooling his kids! Billie Eilish was an unschooler! Caitlin Moran! Elon Musk started his own self-directed learning centres!

One thing these people have in common is some degree of privilege and/or coming from an arty/bohemian background, where you expect the children are continually surrounded by interesting influences. This is one of the criticisms of unschooling: that it can only work for a self-selecting group of families who have some ability to make it happen. In our case, the fortunate aspect is that we both work from home. But this isn’t the case with all unschoolers. Some go to a tiny but growing network of self-directed learning centres, which are more akin to conventional schools, except the children can pursue their own interests, with adults on hand to assist and guide as needed. There is a good argument for having a self-directed learning hub in every community in years to come.

The unslippery slope

There are arguments against it too. One interesting aspect of this experience has been plugging into a range of overlapping debates about school, education, neurodiversity and young people’s mental health. All these debates have grown in urgency in the wake of lockdown, and they all connect to even bigger questions about the changing labour market (for which education is partly a preparation) and ultimately about life itself. What makes a good life? What makes a good childhood? What are the responsibilities of a parent? How do you measure success? Does someone come out with clipboard at some point and tell you how you did?

While I’m still trying to make sense of all these questions, my overwhelming impression is of deep societal shifts taking place. US psychiatrist and rationalist Scott Alexander has written in characteristic detail about the effects of lockdown on educational outcomes, provisionally concluding that the effects of missing a year of school, or even the entirety of school, are far smaller than you would imagine.

In a subsequent post, he weighs the arguments against home-schooling and unschooling. One of the most enduring is that school acts as a social safety net. For children at risk of abuse or neglect at home, it is one of the few points of contact with the wider world, where a professional might spot warning signs. This has been used as a ‘slippery slope’ argument against home-schooling and unschooling. But as is often the case (see last post), the analogy is more slippery than the slope.

For one thing, the idea that school is the most effective way to tackle domestic child abuse raises the question of why so much takes place in a society where school is already the default. It also discounts the many children who have been exposed to trauma within school, ranging from serious abuse to internalised anger and mental health issues that only surface later in life.

The deeply embedded assumption that school is synonymous with education means we see these traumas as regrettable ‘bumps in the road’ or things that somehow toughen us up for later life. But later life includes no environment as peculiarly controlling as even the most liberal-minded school. R.’s school was covered with slogans from the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, but I could never work out how that human rights framework maps onto a place that children are compelled to attend, and where you give up most of your personal freedoms when you walk in the door. You can think of that as good or bad, necessary or unnecessary, but ‘rights’ is an odd framing for it.

Why am I writing this?

I’ve asked myself that question several times while writing this. It’s not because I have blindingly insightful answers to all the big societal questions above. Nor is it because I want to become an uncritical evangelist for unschooling. The truth is, we have our wobbles and moments of cold dread – what if we’ve fucked up? What if we’re deluding ourselves and messing up his life?

But we remind ourselves that every parent has similar worries. School gives the illusion of predictability about the future: the reassuring milestones of grades achieved and prizes won. But no one knows how it’s going to work out over the course of a life. The person with the clipboard never arrives.

We also remind ourselves not to compare our unschooling path with some idealised version of how school might have worked out. We went through enough to know things weren’t going to work out in a conventional way. We might have forced the square peg through the round hole eventually, but he was already misshapen and close to shattering. We feel for the many children who don’t get the chance to find another way.

The reason for writing is twofold. First, it’s a way to ‘come out’ as people who have chosen this path, which inevitably attracts some eyebrow-raising and social disapproval. On a practical level, it’s easier to do that by writing one post rather than having multiple conversations. It may be a useful time-saver to refer people to this post in future.

Secondly, there are academics and policy-makers who will ponder the big societal questions more deeply and productively than us. But we wanted to add ourselves as one tiny data point in those conversations – another of the many families who, through a combination of push and pull, end up outside a system that is seen as natural and inevitable, and to which no state-funded alternative is on offer.

A quick word on the A-word

Autism adds a difficult wrinkle to all this, in that it’s an insufficiently understood area in its own right, even before you play it into the larger discussion around schooling. While R.’s diagnosis has been vital for us, recent events also make you wonder to what extent it’s pathologising behaviours that, once you remove them from the context of school, don’t seem as dysfunctional.

These days, R. hosts live streams on his YouTube channel, in which he is simultaneously playing a game while interacting with peers from all over the world. Hearing him in full flow – hosting the conversation, acknowledging comments in real time, welcoming newcomers, defusing arguments with humour, working with moderators to manage bad language – you wouldn’t suspect he had any difficulties socialising in school. But this is a different context, where his need for control and narrow focus on a particular interest are a feature not a bug – and he is interacting with a self-selecting group of kids who share that interest.

Autistic was already a big label for R. to carry around, and now he has another in Unschooler. But they’re both just words. He is in the process of defining himself, and it is amazing to watch it happen.

The end of the beginning

We’ll only know in retrospect, but it’s possible that sharing this post marks the end of the deschooling phase for me and Sue: a way to process our new reality and begin to ‘own it’ in some way.

As for R., it’s the start of a long journey and we’re looking forward to his interests broadening out in whichever directions he chooses. In the meantime, he is gradually rebuilding his self-confidence. The other night, I talked to him about his YouTube channel, which he is single-mindedly working on growing. (I would link to it here, but he wouldn’t like that – he wants genuine organic subscribers, not numbers for their own sake.) He has just passed the 200 mark and his eyes sparkled as he told me how exciting it is. I assumed it was because it’s a nice round number, but he said he has a better reason: it means he has more friends than everyone at his old school put together.

Thanks for reading – please feel free to comment and share.

Loved reading this. My late husband and I took our eldest out of school when he was in his teens. He is severely dyslexic, ultra bright but had been branded one of the naughty children. He flourished at home and is now a very successful record producer.

I am so sad that school is such a difficult environment for so many of our neurodiverse children. With some tweaks, change of attitude and a sprinkle of kindness, the system could be so much better....