Social media, social purpose and social unrest

Facing concerns that social media is fuelling social unrest, a purposeful advertising industry is keen to step up – in any way that increases its power.

In a period of national turmoil, there can be few scarier sentences than: “It’s time for the ad industry to step up.”

But, in the wake of the rioting that has followed the sickening Southport attack, this is the growing cry from across the advertising world.

This week, the chair of Saatchi & Saatchi floated a six-point plan that proposes “bans in one platform to be applied across all” and “bans for spreading misinformation to be preceded by a points system as in speeding”. Other ideas include requiring all accounts to be ID-verified and bans to apply to the person’s identity rather than individual accounts.

Taken together, these ideas are beyond draconian. They paint a picture of a Ministry of Truth-style surveillance state where having the wrong opinions will get you deleted from digital existence. By now, we should all know that what gets classed as ‘misinformation’ today can become accepted wisdom tomorrow. And if the misinformation-spreaders are to be first against the wall, plenty of brands and agencies will shift uncomfortably. Some of those purpose statements and greenwashing ads might elicit a knock on the door from plod.

Over in Campaign, one contributor says “It’s not OK to be funding X [formerly Twitter] at the moment and it’s certainly not OK to sit this one out.” Another talks of the renewed importance of diversity and inclusion, but has a strangely London-centric attitude: “It is important to recognise that these riots are not just a Northern issue; they are happening across the UK and are coming closer to London.” Closer to London—soon they might matter!

All contributors are agreed that Elon Musk’s X is the biggest danger. This is despite the reported role of Telegram when it comes to organising the unrest, and YouTube with its algorithmic tendency towards radicalising users (according to some research).

Mainly because of its owner, X remains the more compelling target. In a separate post, the Saatchi & Saatchi chairman firmly states “not a penny more to Musk”, explaining “Other platforms are irresponsible, twitter is a clear and present threat.”

In the current climate, that line will receive applause from many in advertising, and some of it is understandable. For my part, I find Musk tiresome and his “Civil war is inevitable” post reckless and irresponsible. But I’ve also seen how X has remained the place to turn during realtime events like the Biden debate, the Trump near-assassination and ongoing events in Gaza. And while it spreads ‘fake news’, not least via Musk himself, it’s often the place where fake news gets called out first. The introduction of Community Notes has been an effective intervention. And it’s been interesting to see the notes applied to advertisers including Samsung and Apple—I suspect that’s part of the reason for advertisers getting cold feet (and I imagine it will be reined in as a result).

Now Musk is going legal with advertisers, targeting a lawsuit against the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM)—the industry body set up by the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA), launched in partnership with the World Economic Forum at Davos in 2019, and bringing together corporate and agency members who are collectively responsible for 90% of global advertising spend.

In response, the not-for-profit GARM has already discontinued its operations, while the WFA said it plans to contest the allegations in court, and is confident that it has complied with competition law throughout.

The simplified version circulated on X and LinkedIn is that Musk is trying to force businesses to advertise on X (as though that were possible), and people have been quick to defend the free speech rights of businesses, who should be at liberty to advertise where they like. “Let the market decide!” say the commentators.

But the antitrust case rests on the question of whether businesses can join forces in what is arguably a cartel, and then use their collective muscle to force media outlets into ideological compliance. I suspect Musk ultimately doesn’t have much of a case, as GARM will have been careful with its language—taking pains to emphasise it has no power to force any members into boycotting X or any other platform. Instead, there is softer language about generalised guidance around shared definitions. If Musk has a case, it will be that this nevertheless amounts to a de facto cartel, designed to increase the power of advertisers in a way that goes against the spirit of a free market, and decreases the power of media. I guess the lawyers will figure that out, but other industry bodies like B Corp will be watching apprehensively. They’ve been more explicit about encouraging members to work solely with B Corp suppliers, which is veering close to a pay-to-play cartel. (I talked about that on the Fuel podcast with Keith Smith.)

Meanwhile, some advertisers continue to stick with X. There’s plenty of dross, but a glance this morning shows names like the National Lottery, Sonos, Amazon and the National Institute for Health and Care Research. You have to wonder what a ‘not the penny more to Musk’ agency would do if their client wanted to advertise on X—maybe as a way to include a wider demographic in their health surveys, or because they’ve found their products sell especially well with younger men. (I’m not sure of the demographics of X these days, but believe it skews more male.) Is their agency going to refuse? Or is the same realism going to play out that would apply with any other media-buying choice, like advertising in the Sun, the Mail, YouTube or TikTok? I know ‘where is the line?’ arguments can sound like whataboutery, but when the commercial stakes are high, they can get legal pretty quickly. And if you’re an agency, it’s not ultimately your money or business you’re playing with.

All. Of. That. Said.

I can understand the instinct behind wanting to do something when the social media landscape does indeed contain a lot of toxicity and malign content, and advertisers know they have a structural part in funding it. Surely it’s good to use that power in some way, and hit them where it hurts?

What interests me is what happens next in that thought process. Even without any conscious scheming involved, there’s an inevitable tendency to favour the solutions that hurt someone else and benefit you—and so far the ad industry’s idea of ‘stepping up’ seems to involve all the things that would step up its own power.

Imagine a world where corporations and advertisers could indeed wield their collective power to support only the platforms that meet their guidelines. That would make agencies and their clients pretty influential political players. Imagine a system where platforms are kept “brand safe” by keeping the hoi polloi out, clearing the way for brands to “lead the conversation” about whatever issue is on their minds this week. Imagine a system where every account is tied to a real identity that remains constant across all platforms—a dream for the data-hoovering brands that already follow us around the internet.

All this represents a huge ratcheting up of the ‘surveillance advertising’ model that some non-advertising people blame for the state we’re now in. Social media researcher Jeanna Matthews has written about the “detailed profiles the social media companies build for each of their users [that] make advertising even more powerful by enabling advertisers to tailor their messages to individuals. These profiles often include the size and value of your home, what year you bought your car, whether you’re expecting a child, and whether you buy a lot of beer.” She continues: “The same mechanisms that can recommend a niche consumer product to just the right person or suggest an addictive substance just when someone is most vulnerable can also suggest an extreme conspiracy theory just when a person is ready to consider it.”

You don’t need to be a conspiracy theorist yourself to see how this data harvesting in the service of advertisers creates algorithmic echo chambers at best and radicalisation pipelines at worst. Notwithstanding the soothing words about protecting users’ privacy, a requirement for ID verification on all platforms would be a data-gathering bonanza for online advertisers. All of it accelerates the transformation of the internet from a window onto a shared world into a funhouse mirror that reflects back a warped version of yourself.

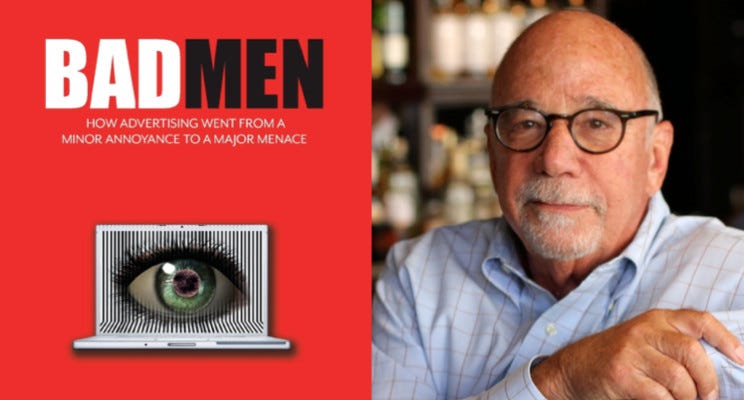

The answer, as Bob Hoffman has tirelessly argued, is to end the tracking model that underpins so much of this. The internet needs advertising—it’s what allows us free access to so many useful sites and platforms. But it doesn’t need the tracking that comes with it. Getting rid of ad tracking wouldn’t solve societal issues at a stroke, but it’s the most radical intervention available. Unfortunately it’s one that would come as a potential cost to advertisers, rather than a benefit. (I say potential cost, but really it should be seen as a benefit, because so much of the advertising would be better and more creative, rather than another pop-up saying ‘We noticed you bought a lawnmower last month—here are 58 more’.)

Bob Hoffman has made this case to the European Parliament—you can read the short transcript here.

Over in the US, and in a similar spirit, Congresswomen Anna Eshoo and Jan Schakowsky and Senator Cory Booker have proposed the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act. It’s worth watching the campaign video above, and here’s how they sum it up in their own words:

Eshoo says: “This pernicious practice allows online platforms to chase user engagement at great cost to our society, and it fuels disinformation, discrimination, voter suppression, privacy abuses, and so many other harms.” Schakowsky says: “The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act will put a stop to this repulsive practice and therefore protect consumers by removing the financial incentive for companies to exploit consumers’ personal information and help stop a morass of online harms.” Booker says: “Surveillance advertising is a predatory and invasive practice. The hoarding of people’s personal data not only abuses privacy, but also drives the spread of misinformation, domestic extremism, racial division, and violence.”

And what does the advertising industry say, when the violence flares up?

Nothing about getting rid of tracking, but plenty about scaling it up.

Some of the calls for the ad industry to ‘step up’ no doubt have good intentions behind them. But there’s a saying about where good intentions can lead. It’s not enough to trim surveillance advertising at the edges to cut out X or whoever is the current bête noire, then keeping the whole show on the road. Nor is it about continuing to buy the ads, but covering yourself with self-consciously purposeful messages. It’s about a radical change that shifts the rules of the game.

For now, I suspect we’ll see a lot of advertisers talking about anything but tracking, and continuing to turn the attention onto useful villains like Musk. But I’d love to see more agencies and clients joining the calls for an end to tracking and a revival in non-creepy, non-stalky, creative advertising. That would be a good way to step up.

Thanks for reading—please buy my book. And if you already have, a rating or review on Amazon is a useful way to boost it.

Thanks for drawing attention to this. The levels of voluntary "stepping up" during covid were equally concerning. The eagerness of commissars to step into compliance culture, for a buck, is one of the deep problems for the system, across domains. I think back to every single corporate website with a covid warning at the top, no matter how unrelated to the product or service. The man hours lost to implementing this slow-burn public nudge overstep must have been immense. Add to that, Facebook "change your pfp to "I got my vax"", whixh i think was insidious, powerful, unaccoutable messaging. Things can spiral out of control very quickly.

Well done Nick insightful stuff and you're absolutely right to question the role of tracking and its effects on creativity.