Hello again. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

In this post, I want to talk about a skill that was once considered central to advertising and other forms of persuasion, but which has (I think) become marginalised, undervalued and even regarded with suspicion in recent years. The best technical description for it is cognitive empathy (more on which later), but you can also call it perspective taking—or the imaginative act of standing in the reader’s shoes and trying to see things from their point of view.

When I say this skill was once considered central to advertising, I have a few other writers to back me up. They all appear in The Copy Book—an advertising book first published in 1995 and updated in 2018 (when I was fortunate to be among the 51 writers featured). Each writer contributes a short essay about their approach to the craft, followed by examples of their work. By general agreement, it’s the essays that are the most interesting part. It’s surprisingly rare to see people talk in detail about the practical skill involved in their day job. And while much of the work feels of its time (including many long-copy press ads from the 1980s and 1990s), the thinking behind it is still sharp and relevant.

Or at least, it should be relevant.

As I say, this is the problem I want to talk about.

1. Writers on readers

First, let me hand over to a few other writers featured in the book. Bear in mind, these are all writers given a rare opportunity to talk about themselves. But they keep talking about someone else: the reader.

“If you want to be a well-paid copywriter, please your client. If you want to be an award-winning copywriter, please yourself. If you want to be a great copywriter, please your reader.” Steve Hayden

“Know your target audience. Not intellectually, but intuitively. Think like them, empathise with them, identify with them.” Mary Wear.

“You should write from the standpoint of the reader’s self-interest.” John Salmon.

“There’s one short, simple word you should use a lot. Read your copy and check that ‘you’ appears three times more than ‘I’ or ‘we’. This helps you write about the subject from the reader’s perspective.” Steve Harrison

“Empathy really is all.” Barbara Nokes

Empathy really is all. Those might be the four key words in the book—I’ll return to them in the next section. But for now, you get the idea: the secret to being a writer is to think about the reader. How are they likely to be feeling when they encounter this ad? How would you feel if you were them? What would make you read instead of turning the page? What objections are likely to be forming in their head as they read this sentence? How can you answer them in the next one?

As several writers point out, this involves more than blunt demographic data. Janet Kestin, co-creator of Dove’s ‘Real beauty’ campaign, says: “Imagine yourself into the skin of the woman they’re making it for. Who is she really? (I promise you she’s not a female, age 18-54, with 2.4 children and a husband who earns $43,000 a year.)” Bob Levenson, former chairman of DDB, makes a similar point: “‘Males, 18 to 34’ or ‘Households above £30,000 pa’ are categories worse than useless; they are destructive.”

As Janet Kestin describes it, seeing things from the reader’s point of view is itself a creative act: it’s about imagining yourself into their position. They may be a real person or an amalgam you create from various sources—conversations with strangers, observations from real life, informal field research, even the dreaded focus group—but either way, you approach that person as an equal. Bob Levenson advises: “Keep in mind that your prospect (even of your own creation) is likely to be smarter than you are and much warier. He is, after all, not in advertising; you are.”

One last quote, this time from Tom Thomas: “If there’s a simple truth that sums all this up—and there isn’t but here goes anyway—it’s that people who write ads should assume readers are at least as bright as they are. This has the advantage of being true some, maybe most, of the time. It also makes for honest writers—and credible ads.”

By the collective account of 51 writers, advertising is not only about taking the reader’s perspective—it also involves doing it in a spirit of respect and humility. You’re intruding on the reader’s time, trying to persuade them to change their mind about something, whether it’s buying a product, supporting a charity, applying for a job, or voting for a political party. To do that successfully, you need to understand, and respect, the mind you’re trying to change.

We’ll come back to why that might be a particular challenge today.

But first, let’s zoom out from advertising, because this exercise in perspective taking has a role to play in other things—for example, saving humanity.

2. Cognitive empathy really is all

Anyone who made it to the end of my recent appearance on the Call To Action podcast will have heard me enthusing about Robert Wright—author of Nonzero, The Moral Animal and Why Buddhism is True, writer of the Nonzero newsletter, and seasoned commentator on US foreign policy. His overarching concern is what he calls the Apocalypse Aversion Project—addressing the existential problems facing humanity, including nuclear annihilation and climate catastrophe. In order to avert these and other fates, he argues that we need to foster one skill in particular: cognitive empathy.

The addition of the word ‘cognitive’ is intended to separate the concept from the everyday ‘I feel your pain’ kind of empathy. Other descriptors include cold empathy or strategic empathy. The idea is that cognitive empathy should carry no implication of sharing, endorsing, sympathising with, or defending the other person’s point of view. It’s simply the neutral act of seeing that point of view. Gamers might recognise an analogy with the ‘player point of view’ mode available in some computer games, where you can switch perspectives to see the battle as your opponent is seeing it, including you charging towards them with an axe. That person might still be your enemy, and you may not endorse their attempts to dodge your axe and torch you with a flamethrower. But seeing the game from their point of view could open your eyes to other variables, like a third player creeping up behind you with a submachine gun.

The problem is, it’s a continual effort to decouple the idea of cognitive empathy from emotional empathy. And accusations of the latter are used to discourage the former. For example, right now, any political commentator who engages in cognitive empathy with respect to Putin can easily be cast as an ‘apologist’ for a war criminal. It isn’t a fair accusation—if a chess player attempts to read the game from their opponent’s point of view in order to predict their next move, you wouldn’t call them an ‘apologist’ for their opponent. But it often feels fair, because our instinct is to elide cognitive and emotional empathy. For example, we use the phrase ‘I see where you’re coming from’ to defuse arguments, because it’s a tonal gesture towards reconciliation. But technically it shouldn’t indicate anything like that—‘I see where you’re coming from and wow, that is a dark and twisted place’ is an equally valid implication (and often the one we privately hold in our heads).

I’m making this detour from advertising to highlight that cognitive empathy is an idea with bigger implications than selling washing powder. It’s a mental discipline that can counteract the effects of tribalism, confirmation bias and polarisation stoked by ad-funded social media (see two posts back). And this skill can be applied to everything from preventing wars to convincing people of the reality of climate change.

But there is a direct connection to advertising, because people in advertising are supposed to be good at this stuff. If you want to connect with mass audiences and persuade them to do something, then you call the advertisers. In these times of political polarisation, culture wars and entrenched tribalism, your ad agency will help you cut through the noise and connect to a world that is getting harder and harder to understand.

3. Wait, stop laughing

If I’m empathising with my median reader correctly, that last sentence will have elicited a rueful grin. The idea of ad agencies as specialists in cognitive empathy is as credible as the idea of Kendall Jenner as a defuser of civil unrest.

A 2019 white paper by Andrew Tenzer and Ian Murray brought some hard data to this question. In The Empathy Delusion, the authors use 14 psychological test questions to assess respondents on levels of cognitive empathy (neutral perspective taking) and affective empathy (emotional empathy). Their finding is that ad people score about the same as everyone else (30% scoring highly, compared to 29% of non-advertising people). Not terrible, but also not great for one of the skills that advertising claims as a specialism.

The same paper offers evidence that empathy is applied unequally—people on the left have a stronger tendency to judge their out-group more harshly, which is significant when 44% of advertising people self-identify as being on the left, compared to 25% of the modern mainstream.

But in this post, I don’t want to dwell too long on that part of the problem. By now, I think most people in advertising have at least some awareness that much of their industry exists in a bubble, and needs to find ways to get beyond it.

Instead, I want to talk about the answer, which I think comes in two parts. And my contention is that the industry only ever talks about the first part, and does it in such an over-simplified way that it obscures and obstructs the second, equally important, part.

Briefly, the first part is diversity. And the second part is cognitive empathy.

4. Slightly less briefly

Both parts became clearer to me while flicking through The Copy Book recently.

One jarring aspect of the book (certainly in its 1995 form) is the preponderance of white male writers—something that has been partially rebalanced over the years. But it’s quite possible to look at the original line-up, cross-reference it with all the talk of ‘seeing the reader’s point of view’, and conclude that this is a highly cancellable book. How can these people presume to see multiple perspectives when they come from such a narrow range themselves?

That goes to the first part of the answer: diversity. It has rightly been the focus of much attention in recent years. One way for advertising to break out of its bubble is to bring a wider range of people in—and give them good reasons to stay in.

The over-simplification comes in addressing only the forms of diversity that show up in the team photos—and perpetuating or exacerbating other inequities as a result. The original line-up in The Copy Book may have been narrow on race and gender, but it almost certainly contained a greater diversity of class and educational background than any equivalent line-up today—when we are confronted by confounding statistics, such as 69% of BAME people (an outdated term) in advertising having been privately educated, according to the 2020 IPA census. It should be possible to make progress on more than one front at once, but class and educational background are undoubtedly key variables when it comes to writing for a mass market.

Similarly, I’ve no idea how the Copy Book line-up would rate in terms of neurodiversity, sexual orientation, political leaning, religious belief and all the lesser factors that have a surprisingly significant impact on life outcomes—height, good looks, levels of introversion and extroversion. But I do know that achieving truly representative diversity across all these dimensions is a goal you have to strive towards in the knowledge you can never totally succeed. There will never come a day when every agency has the exact proportional mix of all these groups reflected faithfully in its workforce—and even one that did would only have found half the answer.

5. Slightly less briefly (continued)

The other half is to nurture the skill that enables people to reach beyond the bounds of their immediate identity group, which is ultimately a group of one. One paradox in the diversity conversation is that people say ‘If you want to market to us, then hire us’—implying that the individual can be taken as representative of the group. But the same people rightly object if they are hired and treated as the go-to expert for their identity group—implying that no individual can, or should be expected to, represent anyone but themselves.

Both halves of the paradox contain some truth. It’s self-evidently the case that life experience (what we now call lived experience) is a valuable source of insight—and much of this maps onto identity-based groups. If you’re selling sanitary pads to teenage girls, it may help to have been one yourself at some point. But equally, it’s patronising to hand the project to the all-female team because ‘they’re bound to get this stuff’. There’s no firm middle ground between those points. Lived experience matters, but in relation to any given individual, the realm of unlived experience will always be immeasurably larger. And all human interaction is an attempt to reach into that realm and make a connection—however imperfect, contextual and fleeting.

Cognitive empathy is the skill that allows people to do that successfully. But it’s not a mystical gift that is innate to some and not others. It’s a combination of method and something close to mindfulness. Some of the writers in The Copy Book describe the mechanical process of having conversations, doing research, visiting the factory floor, or standing around in a supermarket. All those inputs get fed into a way of thinking that is inherently imaginative. You’re continually doing something that the strictest exponents of identity politics would say is either impossible or problematic: trying to identify meaningfully with someone who isn’t you.

6. A perspective shift

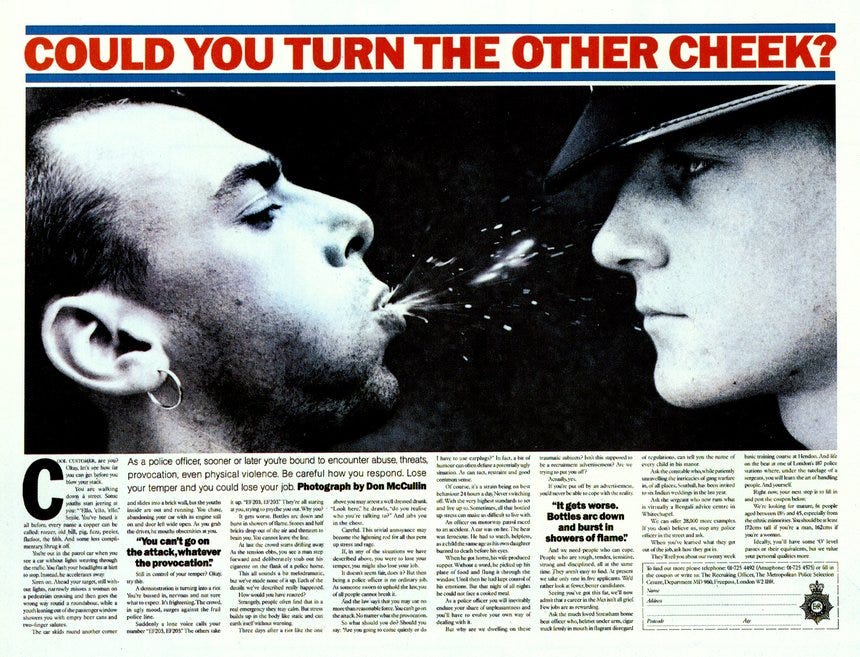

One copywriter not featured in The Copy Book (maybe because he described himself primarily as an art director) is John Webster. I remember seeing this Guardian ad by him when I was 14.

The public-information-film style might feel dated now, but the message remains powerful: a simple parable about not rushing to judgment, not succumbing to confirmation bias, consciously taking into account that there might be other aspects of the story that you’re not appreciating. To teenage me, it felt like genuine wisdom inserted into an ad break.

I’ve come to learn that The Guardian is less reliable on this front than the ad suggests. But I give it credit for seeing it as a value to which to aspire. And I definitely give credit to the writer—a man with a brilliant instinct for seeing ads through the eyes of ‘ordinary’ people rather than his industry peers.

It would be fitting to use his ad as inspiration for a shift in advertising culture today.

7. A culture of cognitive empathy

The Empathy Delusion may have shown that advertising has no special claim on cognitive empathy. But that doesn’t mean it can’t get better at it. By treating it as one half of the answer, alongside diversity in all its forms, advertising can start to reclaim its cultural relevance.

In recent years, the focus in advertising has been turned relentlessly inwards. For brands, the advice has been to search for your inner ‘why’—identify your purpose, then take that noble message out to the world. For aspiring advertising creatives, the advice has been similar: look inwards for your personal purpose, then use your work as a vehicle to bring that purpose to life.

A culture of cognitive empathy would shift the perspective outwards. The advice to brands would be to spend less time analysing yourself and more time understanding your customers. You could start by not thinking of conversations as things you lead. The advice to aspiring creatives would be to find meaning in people more than purpose. Cultivate a wide media diet, take professional pride in your ability to see points of view you don’t agree with, think of yourself as a communicator and persuader—someone who can do it in small-scale ways (designing a flyer for the new pizza place that the owner and her family are praying will succeed), or in large-scale ways (branding an environmental NGO that is urgently looking to change minds and behaviour).

None of this precludes having your own strongly-held political opinions that could influence the work you do and the career direction you take. But in a culture of cognitive empathy, you wouldn’t expect applause just for having those opinions. The applause would be for your willingness to challenge your preconceptions, and put yourself in the shoes of people who might have opinions of their own. In a non-work context, it would still be fine to roll your eyes and say you will never understand Brexit voters as long as you live. But in a work context, it would be taken as an admission of a professional shortcoming.

This applies anywhere along the political spectrum. If you’re a middle-aged Conservative-voting agency owner in Surrey, you might privately think that young people are all pink-haired wokeflakes these days. But in a work context, you should see that as a blind spot you urgently need to overcome. And, in doing so, you’ll create a competitive advantage. Clients should be able to turn to their agency for elucidation about the world. If a despairing healthcare client asks ‘What the hell is going in the minds of anti-vaxxers?’ you should be ready with an answer.

8. Thanks for reading

I’ll end by handing over to another writer featured in The Copy Book, renowned for his work on Amnesty International and this Yellow Pencil-winning Metropolitan Police recruitment ad from 1989. (It’s hard to imagine a police recruitment ad winning anything today.)

Indra Sinha is another writer who prefers talking about someone else: “At its deepest level, it’s all about the reader.” But he goes on to make a passionate defence of speech and writing as tools for communication and persuasion:

“Speech and writing are our most civilised tools for social and political action. This is why we cherish free speech and democracy, why we have parliaments, debates, laws, a universal declaration of human rights, and courts to hear evidence and arguments. But when free speech is stifled, laws are emasculated, justice is denied and writers censured or bullied into silence, what then? What happens when words fail?”

It’s a reminder of a relatively recent time when ‘free speech’ hadn’t been swept up in the mind-numbing culture wars. And it goes to a deep truth about writing that can get lost in the conversation about identity and diversity. If you’re a writer, you have to believe in writing. You have to believe in the possibility of successful communication between people who are different from each other, because we are all different from each other. You might call that my main Thought on Writing, which I’ve been promising for a while in the title of this Substack.

The other thought is this: writing relies on readers, who engage in a reciprocal form of cognitive empathy every time they grapple with the writer’s point of view, without necessarily agreeing with it. So thank you for doing that. You’re one of nearly a thousand readers now—and I’ve been mentally picturing you personally throughout.

Love that Nick, thanks. Dx

Hi Nick, thank you so much for a very thoughtful and insightful article. 🙌🏽 This got my copy and 'real person' mind churning, and I sense that a small can of copy worms may have opened. I have always approached a brief with two hats - "Clare the copywriter" and "Clare the everyday person". Keeps me on track. I totally agree with your (and many other writer's) emphasis on cognitive empathy and the directive to "write as if you're talking to a real person". What can be done, however, to improve a writer's empathy radar? Or, what happens when, for example, a very young writer is trying to imagine the life of a pensioner? As an advertising educator, I have heard some rather funny slash alarming perceptions younger students may have of anyone over, even, um ... 30 ... let alone 65 or 80. What is your stance on aligning the writer's profile with that of their target audience, or 'empathy matching'? Personally, I am split. I get that being a mother, for example, should give you immediate extra empathy for other mothers ... however, I also think that the objective perspective of, for example, a non-parent can provide a different and refreshing perspective. Plus, with proper research, the non-parent might actually be more open to a wider set of experiences outside of just their own. (of course they would need to ensure they explore and talk to a lot of mum's and dad's etc. in order to empathise authentically) I ask this question as 'back in the day' the cliché of 'men should work on sports brands' is still around in new guises, with women working on 'female' products and juniors working on cool, fashion brands etc. I sense this directive is coming quite a lot from clients - they want to see their audience reflected in the creatives working on their brand. Perhaps the answer is simply to ensure you have a balanced creative team working on all, and to educate clients about why this is beneficial 🤷♀️ I am curious about your take. Any thoughts?