The story of why

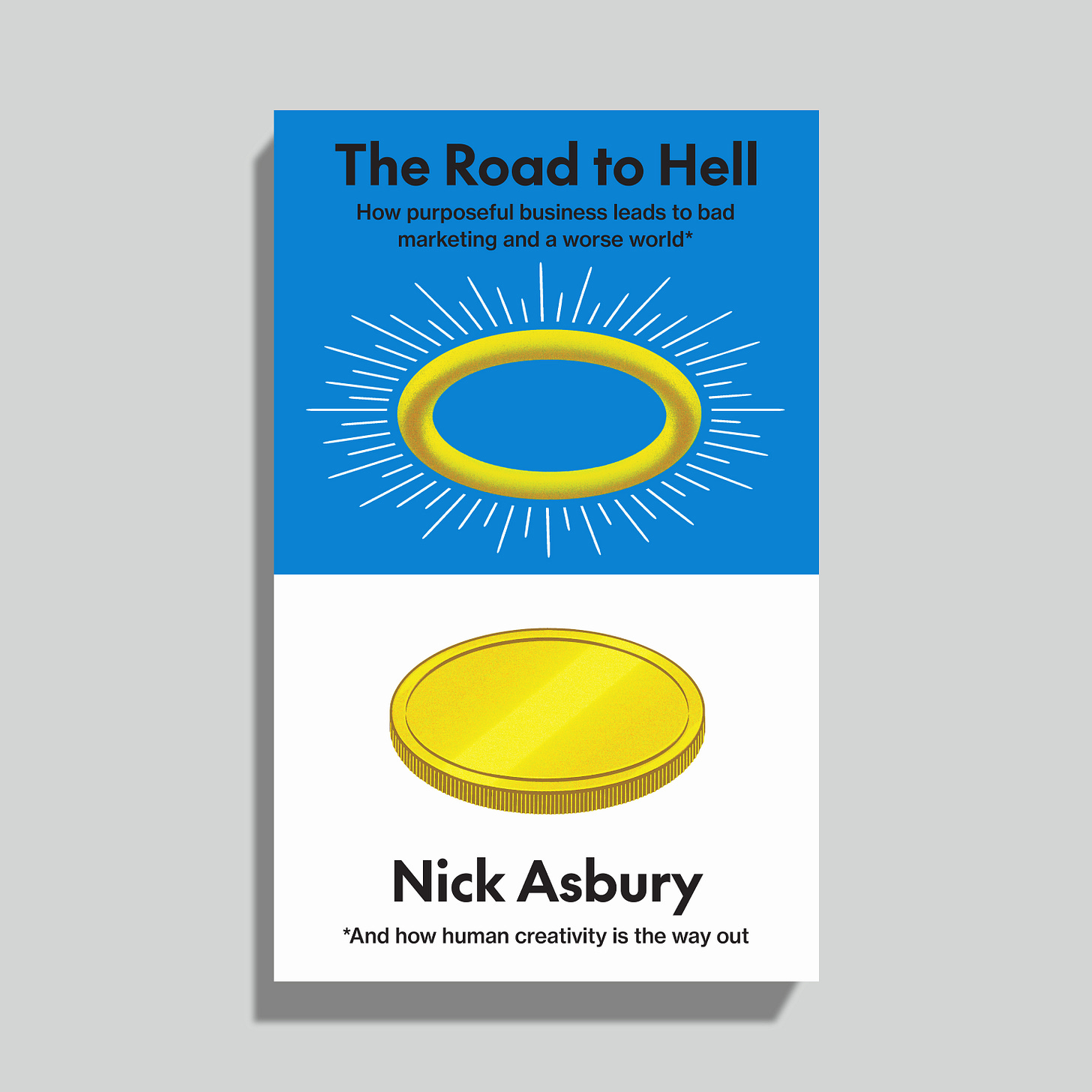

An excerpt from my new book The Road to Hell, examining the case of influential purpose pioneer Simon Sinek.

What follows is an excerpt from my new book The Road to Hell, tackling the case of Simon Sinek and his 2009 book Start With Why.

In other news, I’ve appeared on three podcasts recently, all quite different in tone and content. Check out The Marketing Book Podcast, In Clear Focus and the Fuel Podcast for some interesting conversations.

At the turn of the century, Simon Sinek was an adman, working at Euro RSCG (now Havas Worldwide) and Ogilvy & Mather, before launching his own consultancy in 2002.

It’s common practice in adland to come up with proprietary models that capture the way a brand works. On whiteboards from London to New York, you will find brand onions, brand pyramids, brand houses and brand doughnuts. Sinek’s version was three concentric circles: with the ‘why’ of the brand at the core, circled by the ‘what’ and the ‘how’.

In an ambitious reference to the golden ratio, he dubbed this the Golden Circle and pondered whether it might be the hidden pattern underlying all successful brands and leaders. It lay on the shelf for a while, but then Sinek describes a eureka moment when he realised this model might have echoes in neurobiology.

The initial source wasn’t a neurobiologist, but California actress, Democrat activist and former wife of Dennis Hopper, Victoria Duffy Hopper—daughter of two neuroscientists. Seated next to her at an event, Sinek fell into conversation about the structure of the brain, learning how the outer, rational neocortex was wrapped around the primal, emotional limbic system. “And I realised… that the way the brain works, and the way my little model was articulated—the why, how, what—perfectly overlapped. In other words, I had discovered why marketing works. I had discovered why people do what they do. And that profoundly changed my life.” [Savage Minds interview]

Sinek sought confirmation from a neuroscientist, appropriately named Peter Whybrow. It turned out the model wasn’t quite a perfect overlap: Whybrow advised Sinek to flip the order of the how and the what. But apart from that, there was just enough science to give Sinek confidence in his model, or his ‘discovery’ as he preferred to call it. “It’s not my opinion, it’s biology,” he later wrote.

The biology is contested. Sinek’s version comes from the ‘triune’ model of the brain, popularised by neuroscientist Paul MacLean (pictured above) in the 1960s. The idea is that our ‘lizard brain’ is the most primitive, non-verbal part that functions on instinct. Over the course of evolution, this was enveloped by the ancient limbic system, source of our emotions. More recently, this was encased in a sophisticated neocortex that separates our brains from those of other vertebrates and allows us to make rational, verbal decisions. If you want to inspire people to buy into your brand, you need to dig past the what and the how and get to the why, where the real action happens. “People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it,” Sinek repeats eight times in his book, Start With Why.

Sinek’s advisor, Peter Whybrow, subscribes to MacLean’s triune model. In 1997, Whybrow published A Mood Apart, including a chapter on the lizard brain that opens with a quote from MacLean. And in 2010, Whybrow published another paper, titled ‘After Freud: What do neuroscience advances tell us about human nature?’, which shows continued faith in MacLean’s ideas. Sample quote:

“The human brain is not a single organ but a hybrid: an evolved hierarchy of three-brains-in-one. Thus human behavior is best understood when brain anatomy is placed within an evolutionary context. A primitive ‘lizard’ brain, designed millennia ago for survival, lies at the core of the human brain and cradles the roots of ancient dopamine reward pathways that are the superhighways of pleasure, curiosity and desire.”

Even when Sinek published Start With Why in 2009, this triune model had long fallen out of favour. A 2008 article in the Yale School of Medicine journal is titled ‘A theory abandoned but still compelling’. The article discusses how the science has been debunked, but “the force of MacLean’s personality gave his ideas a special resonance”.

More recently, celebrated neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett included a dismantling of the triune brain myth in her book Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain (2020), which you can hear her discussing with fellow neuroscientist Sam Harris on episode 247 of his Making Sense podcast [or check out the video above]. As she writes elsewhere: “This model, called the triune brain, is a fantasy… The brain didn’t evolve in layers like sedimentary rocks. Rather (in the words of the neuroscientist Georg Striedter), brains evolve like companies do: they reorganise as they expand. The brain regions that MacLean considered emotional, which he referred to as the ‘limbic system’, are now known to contain major hubs for general communication throughout the brain. They control the various systems of the body, and they’re important for many phenomena besides emotion, such as including language, concepts, stress, and even the coordination of the five senses into a cohesive experience.”

I include this scientific detour because I’ve yet to see a debunking of Sinek’s ‘discovery’ anywhere else. This may be a case of Brandolini’s Law, which states that ‘The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it’. There are deep questions about the relationship between emotion, thought and language, but those questions are not reducible to a cartoon model that claims to reveal the truth of humans, marketing, business or anything else.

Nevertheless, Sinek’s book made a deep impression on the business and marketing worlds, aided by a TED talk that became one of the most viewed of all time. From the start, Sinek’s idea of ‘why’ was synonymous with purpose—“By why, I mean ‘What’s your purpose, cause, belief’”. Its power was that it flattered business leaders into seeing themselves as heroes driven by a higher cause, of which business was just the outward expression. And the beauty of the theory was that anyone puzzled by the ‘why’ question was simply confirming Sinek’s model: it’s meant to be hard to answer, because it lies deep in the non-verbal brain.

So if you ask the boss of a widget company, “Why do you do what you do?” she might be nonplussed by the obviousness of the answer: “Well, we do it to sell widgets and make a living, and there was a gap in the market for widgets.” Or she might be forced to grope around for some faux-psychological origin story: “I guess I saw a gap in the market for widgets, and became passionate about how… people had been living for so long without widgets of this particular kind… at this particular price point… so I wanted to… democratise?.. the widgets and maybe… break the taboo?.. around the widgets, and… make people’s lives easier with the widgets… and I definitely want to sell the widgets to everyone… so I guess I’m on a mission to improve life for everyone, everywhere… and encourage the world to… widget itself happy?” Soon the widget company has recast itself as a ‘challenge the status quo’ company that just happens to make widgets.

This sounds like a parody, but it’s the story that Sinek projects back onto Apple (his favoured example of a start-with-why company). The other two leading case studies in his business book don’t come from the business world.

First, there are the Wright brothers. Sinek’s version of events is that they won the race to develop the first motor-powered airplane because they were driven by a stronger internal sense of ‘why’:

“It wasn’t luck. Both the Wright brothers and [their rival] Langley were highly motivated. Both had a strong work ethic. Both had keen scientific minds. They were pursuing exactly the same goal, but only the Wright brothers were able to inspire those around them and truly lead their team to develop a technology that would change the world. Only the Wright brothers started with Why.”

So a fascinating story of incremental engineering innovation is flattened into a simple question of desire—Sinek writes like a sports commentator who declares that the winning team ‘wanted it more’. Meanwhile, he overlooks a key aspect of the Wright brothers’ story, which ought to interest the business community he’s addressing. There’s a reason we’re not all flying on Wright Airlines. Larry Tise, historian and Wright brothers biographer, sums it up like this:

“Most historians treat the Wright Brothers as great American heroes. I see them partly as tragic figures. Once they had the invention, they wanted to be like Henry Ford and Alexander Graham Bell and become rich off their invention and work. They got the patent on their flying machine, and then they didn’t work to further flight. They worked to protect the patent. They became obsessed with making money and protecting the patent.”

There is nothing wrong with this desire to monetise their work, but you have to squint hard to see a ‘start with why’ narrative anywhere in the picture.

The other example is Martin Luther King—which, no doubt unfairly, brings to mind David Brent’s admiration of Nelson Mandela in British comedy The Office. On the face of it, this one stands up better. As Sinek notes, King said “I have a dream”, not “I have a plan”. But if that dream was King’s ‘why’, it was one he shared with many who went before him. Sinek’s view misreads the true dynamic of King’s Lincoln Memorial address, where the line immediately following the first instance of “I have a dream” is: “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

Throughout the speech, King anchors his case not in his own inner ‘why’, but in the values of the audience he is trying to persuade. Emancipation wasn’t a threat to the American dream, he argued, but instead represented its true fulfilment:

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

This is the clear ‘what’ and ‘how’ that runs throughout the speech. You have the what: the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Christian values, the liberal tradition. This is ‘how’ you live up to them.

All this is a contested area, and King’s speech was only one moment in a lifetime of tough political activism. But reducing his life to an inspirational parable for CEOs is unserious.

A year after the publication of his book, Sinek recorded an interview with Adam Fish on anthropology podcast Savage Minds. He recounts the origin story of the Golden Circle, then moves on to wider thoughts about the distinction between for-profit and not-for-profit organisations, and the nature of corporate leadership.

Some might wonder if the existence of not-for-profits is a problem for Sinek’s idea of purpose-driven companies. After all, if you were truly driven by a higher purpose that goes beyond profit, wouldn’t you choose to be a not-for-profit in the first place? But for Sinek, it’s a matter of language:

“All organisations are for-profit; it’s just how they measure their profit that’s different. For-profits measure their profit in dollars and cents; not-for-profits measure their profit in terms of making a particular impact in the world.”

This curious distinction leads Sinek into further thoughts about the superiority of for-profits when it comes to executing on their cause:

“You talk to non-profits all the time and they’re carrying a lot of dead weight in terms of talent, but they are loath to fire anybody because they’re so devoted to the cause. But in reality they’re bad employees. A for-profit would have no problem trimming out dead wood because they need people who produce. It’s the social entrepreneur who understands that what you need to do is combine those models. Strong on cause and strong on structure. Not one or the other: two sides of the same coin… The best organisations function as if they were social movements.”

Many will recognise the criticisms of the not-for-profit world, which can be prone to institutional inertia. For Sinek, the answer is not to improve that world, but to look instead to cause-driven corporations. And the way they should function is through strong, purposeful leadership, not consensus or democracy.

“Consensus-driven organisations don’t work… The best form of government is the benevolent dictatorship. And the same is true in organisations. The whole idea of consensus is lowest common denominator. How do you please as many people as possible? You end up with something incredibly diluted. Look at any congressional bill that passes… Rare are the bills that are truly profound and great because you have to please as many people and as many constituents as possible. So a leader is the single person, or no more than a pair of people, at the top, who explains their vision of the world and asks those in their organisation who believe what they believe to help build it. Consensus is not the way. There is only one vision and there can be only one vision.”

There is only one vision and there can be only one vision. This is where Sinek’s model of social purpose ends up: for-profits grappling with social causes based on the gut feelings of their benevolently dictatorial leaders, with the idea of employee consensus a tiresome distraction. It might be an efficient way to make decisions on the price of your widgets or the location of your warehouse. But when it comes to adopting social causes, and pushing a ‘make the world a better place’ agenda, many would see the benefits of slow political consensus, based on the same Constitution that Martin Luther King embraced.

Sinek has much to teach the marketing world, but none of it is about purpose. His skill lies in marketing and rhetoric. He knows the power of a three-word imperative slogan (Just Do It… Take Back Control… Start With Why); he knows the power of repetition (note the many examples in the TED talk); he knows the importance of scienceyness to persuasion (like the 1920s marketer who unearthed the obscure term ‘halitosis’ to start selling Listerine); he knows words like ‘discovery’ are more powerful than ‘theory’; he knows that branding himself an ‘optimist’ is a power move to cast any questioners as pessimists and cynics; he has the gift of spoken fluency that makes his ideas more compelling in person than on the page.

And he knows that people generally don’t look at evidence claims too closely— especially when the story is so seductive to the business leaders he’s addressing.

And so it transpired. Global business leaders, so maligned after the unregulated excesses that led to 2008, would go on to present themselves as the self-regulating moral heroes of the next decade, claiming to do social good while doing very well out of it. The rest of that story is told and unpicked in the book.

Please order a copy and/or consider leaving a rating or review—all helps get the word out. And thanks as ever for reading.

Simon Sinek is the human manifestation of LinkedIn

Could not have smashed that like button any harder. I come at this from a slightly different angle than you (comms), but I really see corporate purpose culture as actively toxic, both to employees and wider society.

When you quite clearly and demonstrably operate as a profit-led company – which is totally fine, btw – and yet tell everyone your purpose is not profit at all, it's blatantly dishonest. Worse, this is then imposed on employees in a bizarre gaslighting loyalty test, as they often have to justify their performance in the light of these values which everyone knows aren't real. It all wastes loads of time and absolutely decimates engagement. Because of COURSE we all crave purpose and meaning and good stuff – but we can all smell bullshit, too.

Also, claiming the right to define the moral values held by employees is kind of an unprecedented employer overreach. When a company claims that it prioritises its values over profit, which is the core thesis of 'purpose-led', the company is bound (at least in theory) to hire for values over skills. I could be the best candidate but fail the interview for not believing hard enough. This is not how you do business, it's how you start a cult. Normalising this behaviour is bad!

Sorry, rant over. 😅 I was just really excited to read someone actually analysing this stuff. I'm definitely getting your book!