The Road to Hell: Q&A

In which I present five arguments against The Road to Hell (my critique of purpose) and then argue with myself.

First of all, thanks to everyone who read The Road to Hell, my three-part case against Purpose. It was based on a talk I gave in Ghent—you can watch the video here.

The feedback has been encouraging, and it’s especially heartening when it comes from people who might otherwise have been sceptical. Recent example: “As a social entrepreneur and passionate advocate of ‘making a living AND making a difference’, I really didn’t know what to expect and did wonder if your name may be muttered somewhat disparagingly afterwards. But I actually found myself agreeing with you…”

I’ve not received much direct pushback, maybe because it’s hard to get widespread traction for anything you post online these days. But it doesn’t stop me arguing with myself internally—I always have a persuadable-but-sceptical reader in mind when I’m writing this stuff, and sometimes that reader makes decent points.

So in this post, I want to list five arguments against my position. Each one could prompt a full-length post in its own right, but I’ll try to answer them briefly. Consider it the Q&A at the end of the talk.

This is the most common argument I hear, and I think it’s misguided historically, conceptually and pragmatically.

Historically, it doesn’t track how purpose got to be such a big idea in the first place. From the beginning, it was always about social purpose. That’s what made it feel different and new, after decades spent talking about brand ideas, visions, missions, essences and propositions. One of the early proponents was Jim Stengel, who left his post as Chief Marketing Officer at Procter & Gamble in 2008. According to his own biog, “This bold move was Jim’s first step on a new mission to share his passion for growing business through a focus on higher ideals.” The result was Grow: How Ideals Power Growth and Profit at the World’s Greatest Companies, published in 2011. This was one of the founding texts of the purpose movement, and it was unambiguously defined as social purpose. (Again, if you want to see how flimsy and unscientific it all was, Richard Shotton is your man.) To argue that purpose was a good idea that got hijacked by social purpose is simply misreading the history.

Conceptually, once you remove the social dimension, purpose becomes a pretty vanilla concept. It might just as well be mission, vision, goal or proposition—all of which are familiar and conventional ideas. Advocates of non-social or ‘commercial’ purpose like to argue that a brand can’t just be defined by the goal of making a profit—it surely needs a more distinctive and unifying vision than that. I agree, and so did all marketers long before 2008. They just used words like vision, mission, essence, idea and proposition instead. The reason people like to use the word ‘purpose’ now is that it feels fashionable and current. And the reason it feels fashionable and current is that social purpose made it feel that way. There’s a certain vibe about the word purpose. It has an in-built moral valence to it. If we say someone is purposeful or has a sense of purpose, it sounds like a good thing, not just a neutral statement. (It would sound odd to talk about a serial killer being driven by a sense of purpose, even if it’s technically accurate.) Purpose retains this value-laden dimension even when you say you mean it purely commercially—which relates to the next point.

Pragmatically, it’s just futile to use the word ‘purpose’ in the non-social or commercial sense. However much you clarify that this is what you mean, you will forever get tangled up in the wider social purpose debate—because that’s what everyone else means. It doesn’t matter if an ad agency writes its own careful definition of purpose as long as BlackRock and all the multinationals in which it invests are using an entirely different definition. It doesn’t matter if you keep clarifying you mean commercial purpose when every purpose awards scheme and every press article about purpose automatically means it in the social sense. If you really want to make the conceptual distinction clear, then use a different word. ‘Proposition’ shares the same Latin root as purpose and I would say it’s a more honest word to describe what you mean by ‘commercial purpose’. A proposition is something you can change over time as the commercial context changes. A purpose suggests it’s in-built and enduring, in a way that just isn’t the case.

In truth, I think non-social or commercial purpose people cling to the word because, on some level, they think it’s helpful for business in the short term. It means you can still attract all the clients who believe they need a social purpose, while not looking completely out of touch to those who don’t. The ambiguity is strategically useful. And I can’t exactly argue with that—I might even do it myself if I was running an agency. But it’s also a major part of what sustains purpose as a concept and conversation. If you secretly wish the tiresome purpose debate would go away (or loudly complain that it should), then play your part: stop using the word.

I’ve heard this bothism word from a few sources and I’m surprised people can’t see how empty it is as a concept. The idea is that some questions have an either/or answer, but others have a ‘both’ answer, and a bothist is inclined to approach problems in that frame of mind. To which, I say—fine, but how do you know which are which? You presumably think some questions aren’t both—both climate change and climate denial, both pro-life and pro-choice, both raise taxes and lower them. Calling yourself a bothist just defers the argument. Is purpose one of the both questions or one of the either-or questions? Well, that’s what we were arguing about before you came in and used your new word.

But on one level, I can relate to the compromise-seeking instinct. Many debates follow the Hegelian pattern of thesis, antithesis and synthesis—synthesis being a ‘third way’ that unites the opposing ideas into something new. You could call this a more sophisticated form of bothism.

But the argument is then about where the true synthesis lies. Since my first article on purpose in 2017, I’ve been making a case for a different kind of synthesis: a rejection of purpose that nevertheless retains the idea of ethics and responsibility in business. If the thesis is ‘yes, purpose!’ and the antithesis is ‘no, profit at all costs!’, then the synthesis is to reject the delusion of purpose, but retain and redirect the concern for ethics that motivates many who support it. That’s the higher plane on which opposing sides can unite. But it’s an actual intellectual step, rather than a shrug of ‘both’ that amounts to no insight at all.

And as a piece of strategic advice to businesses, bothism is redundant. If the idea is to do a bit of purpose here, bit of selling there, and see what works, then it’s not really purpose you’re talking about at all. It’s just some cause-related marketing tactic that you’re turning on and off like a tap. I could call this argument tapism, but I don’t see why that would make it any more convincing.

This is a widespread claim and I’ve yet to hear convincing evidence in favour of it. Whenever I look, I find obvious counter-evidence. Just as one example, in this post about Ukraine, I cited an IPA/Opinium poll about consumers’ attitudes to the response from brands. Only 15% of all adults wanted brands to reflect the crisis in their advertising campaigns—and this number was lower in the younger age group, where it was only 11%. On a separate question, only 23% of 18-34 year olds supported brands even ‘speaking publicly’ about their position on the war. How does that fit with the ‘Gen Z expects brands to take a stand’ claim?

That’s just one poll and you can find others to support different views. (With all of them, it’s worth looking at the framing of the questions, checking who paid for the research, and remembering that the reasons we say we buy brands aren’t generally the reasons we buy them.)

But there are some polls that act as truly large-scale, authoritative measures of the shifting political attitudes of mass audiences. Two such polls took place in 2016, when consumers were roughly split down the middle on Leave vs Remain, and Trump vs Clinton. Another poll took place in 2019, when consumers doubled down on Brexit and ‘getting it done’. And in 2020, 74 million consumers—buyers of everything from beer to banking to ice cream to washing powder—expressed their preference for the guy in the MAGA cap.

Yes, in each case, younger voters leant more towards Remain / Clinton / Corbyn / Biden. But even there, there’s a sizeable chunk of Gen Z-ers who don’t fit the narrative. 21% of 18-24-year-old voters chose Conservative in 2019—more than LibDem and Green combined. 31% of 18-24-year-old voters went for Trump in 2020 (based on exit polls where you might expect some to be reticent about it). As with all generations, you might predict an increase in small-c conservative attitudes as they get older. But brands can also just focus on the here and now. If you’re selling to a mass audience, what’s the benefit in taking an overtly tribal stance? And who exactly is wielding this spending power that is ‘pushing’ brands into doing it? It presumably can’t be the older people with most of the money and more of the conservative attitudes.

None of this is meant as a judgment on whether any of the above is good or bad news. It’s just a response to the empirical claim that corporations are being ‘pushed’ into doing this. The evidence suggests they’re not (certainly not by bottom-up pressure—you could point to top-down pressure from wayward ESG metrics, but that’s another story). You don’t even need to invoke the culture war battles like Bud Light or Coutts to make this point. It just doesn’t make sense for brands to fall over when no one’s pushing them. Yet so many brands are doing it anyway. As I’ve argued before, ‘Consumers are demanding this!’ is a cover story for corporations who want to expand their political power. And it’s such a convincing cover story that many people in the corporate world actually believe it.

I take this argument more seriously than the others, but also think it’s seriously mistaken. The reality is that corporate purpose, particularly in the guise of ESG, has been a barrier to effective climate action at scale, which relies more on governments changing the rules of the game than corporations vowing to be good sports. Tariq Fancy, former CIO for Sustainable Investing at BlackRock, had one of the most powerful positions in the corporate sustainability world, and a great vantage point from which to see how the systemic incentive structures actually work. He sounds the alarm in this accessible 15-minute talk, titled The Answer to Inconvenient Truths isn’t Convenient Lies.

Invoking the climate emergency is too often used as a way to distract from the convenient lies or pressure people into accepting them. To pick one example, it’s alarming that one of the main responses to the climate emergency from adland has been Advertised Emissions, which its creators (‘Purpose Disruptors’) claim to be an authoritative framework for measuring the climate impact of advertising activity.

The simplistic methodology has been criticised by the AA, IPA and ISBA, and it’s easy to see why. Listening to a recent Campaign podcast in which Purpose Disruptor Jonathan Wise defended the approach against admirably restrained criticism from ISBA director general Phil Smith, I was dismayed at the succession of bad arguments brought forward. Wise first explains the origins of the methodology in a single IPA awards case study from 2018, from which the researchers (Ben Essen and Caroline Davison) took the claimed increase in car sales and multiplied it by the lifecycle emissions of an average Audi, arriving at the conclusion that this single ad campaign was responsible for 5.4 million tons of additional CO2—equivalent to the annual output of Uganda. Anyone paying attention will spot, among many other problems, the obvious substitution issue where you’re failing to take into account how an increase in Audi sales is mainly an increase in market share relative to (say) BMW. But taking such factors into account would make the overall impact far lower, leading to less sensational headlines.

As usual, the fallback position is: We’re just starting a conversation here. Which roughly translates as: We’re being irresponsibly wrong about a serious subject, but it got us onto this podcast. Pulled up on the lack of peer review, Jonathan Wise even claimed ‘We are in a climate emergency and going through peer review is a lengthy process!’—which ought to be a disqualifying claim for anyone in this area. The best time to start peer review is a year ago; the second best time is now. But it also doesn’t take much peer review to see flaws that are undeniable at first sight. And this stuff has consequences, feeding climate scepticism from people who might otherwise be persuadable, creating a false impression that changing your ad activity has a much more positive impact than is the case, and distracting from serious work elsewhere.

Maybe it’s harsh to single out that one example, but it’s indicative of the way the climate cause is co-opted by the purpose side of the debate, as though there’s a natural alliance between the two. I think committed climate activists (with whom I have agreements and disagreements) would do well to question their allies in the corporate purpose world.

I suspect some people just can’t be argued out of this view—purpose is pretty broadly defined in their heads as ‘trying to be good’, so it can’t be wrong. My view is that purpose is a PR campaign for excessive corporate power and a distraction from real social change. It’s not the counterforce to neoliberalism, but its softer and more acceptable face.

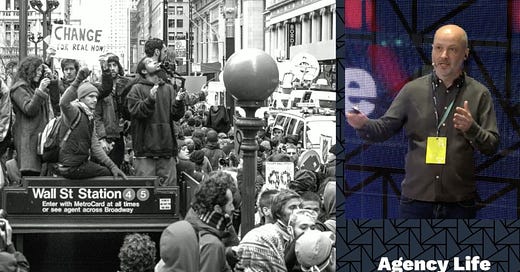

That’s partly why we live in the world we do. After the shock and opportunity of 2008, we’ve waded through 15 years of purpose gloop: a treacle of saccharine statements and moral posturing. Maybe some people think there’s some vantage point in the future from which all of this will look like progress. Such people like to invoke the right side of history, or muse aloud about what their grandchildren will think of them, which always reminds me of the Don Draper meme—I don’t think about you at all. I think the best contribution we can make is to get on the right side of the present as best we can.

As for the alternative to purpose, none of it is preordained. It’s a different world to the 1970s, and I suspect there’s a wider yearning for a sense of purpose that could be channelled somewhere better than brands and ad campaigns. If we can get out from under the blob of purposeful corporations and directionless governments, we might find we are more powerful than we think.

Anyway, I’m pontificating now. But you did ask. (OK, you didn’t.)

Thanks for reading. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, books about design, and occasional songs. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Superb

And may I borrow ‘Tapism’?

Going to find that rather useful :)

I still think you summed it up best in that first article in 2017: Bill Bernbach said that a principle isn’t a principle until it costs you something. Today’s advertisers have turned that around — now it isn’t a principle until it makes you money.

Having said that, I do think there are company (as opposed to brand) principles that can be powerful – for differentiation and particularly for recruitment. And these can bleed into (but should not be the focus of) the brand advertising. One of P&G's core principles is never to release a product to market unless it is at least as good if not better than the existing best in that market. That drives their internal research and product teams, and informs their advertising, but it's never expressed directly to the public.