The billboard backlash

Too many advertisers have forgotten about the social contract that allows billboards to exist in the first place

There is a giant, dark rectangle in Euston station, where a digital billboard used to be. Installed in January 2024, the screen in one of London’s main rail terminals has been switched off by ministerial decree, following scenes of overcrowding, and complaints about an advertising screen projecting commercial messages in place of platform information.

There is a defence for the overcrowding claims—the new layout with the giant billboard and smaller departure screens is reportedly a nudge-theory move to reduce crowd density. But the deeper objection to the billboard is symbolic. Looming over the public concourse and occupying the space that was once dedicated to service information, it’s taken by many as an emblem of a privatised system where the customer is diminished and corporate interests dominate.

The controversial context means ads land differently than they might elsewhere. Sometimes the giant billboard projects ‘rush hour’ jokes that no doubt work better in the concept presentation than they do with weary commuters.

Other times, the billboard projects the familiar messages of the purpose age, as in this campaign by Ovo Energy, in which the company—whose earnings rose 11-fold in the wake of the energy crisis and which recently paid out £2.4m over customer complaint failures—aims to ‘educate’ the public on energy use throughout the UK. (The photo on the right was taken during a power cut that caused misery for commuters, rendering Ovo’s joke… less funny.)

All of this is preamble to a wider point I want to make about billboard advertising, which I think may come as a shock to many ad people today.

Did you know some of the biggest ad legends used to be vocally against billboards?

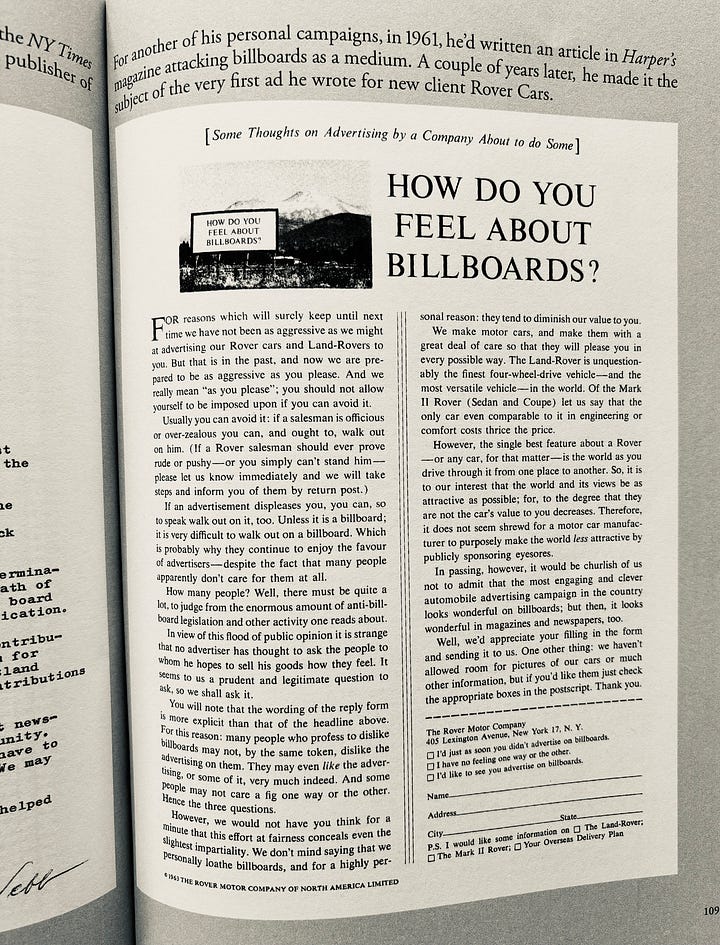

Howard Gossage was personally against the intrusion into the public realm, and managed to get his client Rolls-Royce (above, left image) to run a public consultation on the issue in 1963. All this came in the run-up to the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, which called for greater control of billboard advertising, seen to be taking over the growing Interstate Highway System at the time.

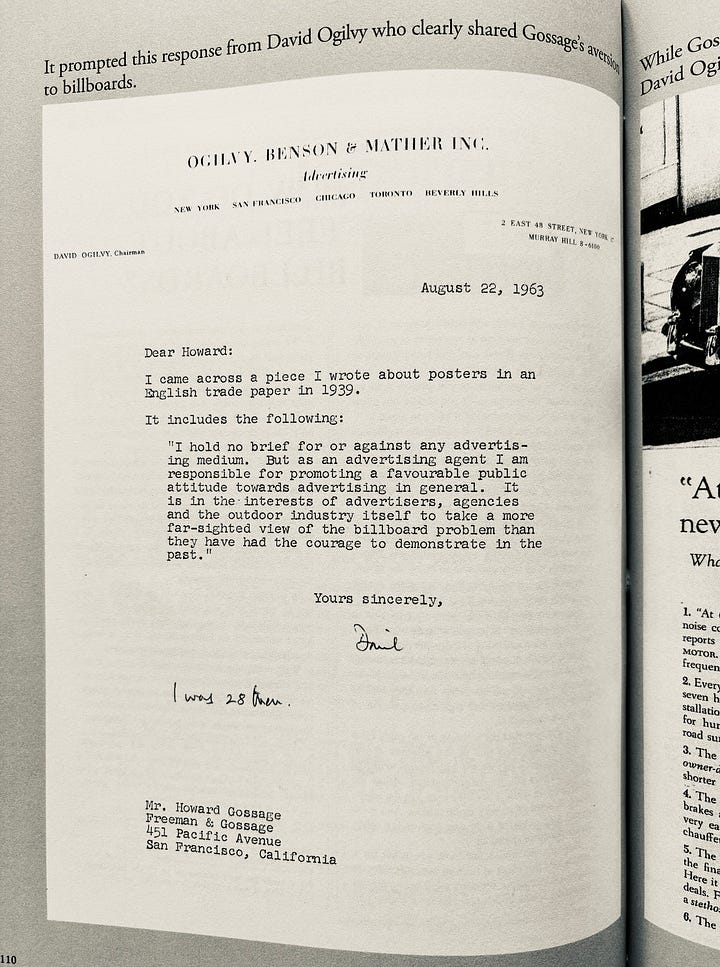

Gossage found a supporter in David Ogilvy (above, right image), who had been railing against billboard ads since at least 1939. “Man is at his vilest when he erects a billboard. When I retire from Madison Avenue, I am going to start a secret society of masked vigilantes... chopping down posters at the dark of the moon. How many juries will convict us when we are caught in these acts of beneficent citizenship?” wrote Ogilvy in Confessions of an Advertising Man. Elsewhere, Howard Gossage expanded on his objections: “I like outdoor advertising… I just don’t think it ought to be outdoors. It’s not a question of aesthetics, it’s simply that it invades… I can’t close it up, I can’t throw it away. It’s just there, whether I like it or not.”

Both the above images come from The Howard Gossage Show, by Steve Harrison and Dave Dye—a brilliant tour of the adman’s career, and an insight into how much industry conversations around billboard advertising have changed.

In The Road to Hell (Kindle & print edition out now), I write about the origins of billboard advertising, and the implicit social contract that has always been involved. There’s no reason advertisers should have an automatic right to put posters up where no one can escape them. It’s a liberty extended to business by society, but it comes with conditions. If advertisers are going to invade the public realm, there’s a responsibility to make it tolerable—ideally by being brilliantly creative and interesting, but at the very least by not being offensive, hectoring, tasteless or fraudulent.

Increasingly, it seems society is unhappy with its side of the bargain. “These ads are in the public space without any consultation about what is shown on them. Plus they cause light pollution, and the ads are for things people can’t afford, or don’t need.” says Charlotte Gage of Adfree Cities, a movement set up to challenge corporate outdoor advertising and reclaim public space for art and community. Elsewhere, The Guardian reports that four in five billboard ads in England and Wales are in poorer areas, quoting research claiming that billboards “negatively affect people’s lives in intersecting ways, by pushing unhealthy products such as fast food and alcohol, encouraging environmentally harmful consumption and lowering mental wellbeing”.

Right now, the political focus is less on the billboards themselves, and more on the products being advertised. Transport for London, Sheffield City Council, Liverpool City Council and others have either banned or are considering banning junk food billboards, citing the negative impact on public health.

All this is distinct from, but related to, the larger issue of the billboard sites themselves. The defence is that they bring in valuable revenue for local councils. But that argument may become harder to sustain if the social costs are seen to be higher, or if the public mood continues to tilt against commercial intrusions of the kind seen in Euston station.

In this context, you might expect advertisers to be sensitive to the changing mood—but the opposite appears to be the case. Not only are advertisers pushing the limits of the social contract, but the self-serving logic of ‘purpose’ is making them feel good about doing so.

So the noble cause of GirlvsCancer is used to justify swearing and sexualised imagery on an untargeted public medium, where everyone is involuntarily exposed, from kids to grandparents.

The ad was banned by the ASA, who acknowledged that it had noble aims and didn’t explicitly spell out the word ‘fuck’. But the context and combination of words and imagery quite reasonably meant it wasn’t suitable for a public medium, whereas it would have been fine in the pages of an appropriate newspaper or magazine.

Rather than prompting self-reflection in the ad community, this led to a bout of teenage eye-rolling about the ASA, who “sound like they’d be a fun guest at a party” according to an article in It’s Nice That. For its part, BBH talked about the need to break the “taboo”, explaining “Our approach might make some people uncomfortable and that’s fine.” None of it evidenced any awareness that billboards are a special context where advertisers have a responsibility to the widest possible audience, some of whom might feel the ‘taboo’ around advertisers showing this stuff to six-year-olds might not need breaking, however noble the cause.

Coincidentally or not, BBH is also the agency behind the post-partum Burger King ads that have divided LinkedIn (and nowhere else). Based on a Burger-King-commissioned survey of women on Mumsnet, which revealed that 39% would choose either a generic burger OR generic fries for their first post-birth meal, the posters showed real-life moments of mums enjoying a Whopper supplied by the sponsor.

Despite the culture war guff about women loving this taboo-busting realism and only mansplaining blokes objecting, the ads evidently split opinion across genders, with some seeing it as welcome realism (albeit based on the surrounding reporting that explained the context in a way that anyone simply looking at the posters would miss)—while others saw it as a depressing commercialisation of a precious moment. Some defenders eagerly told men to be quiet because the ad ‘isn’t for you’—showing remarkable illiteracy about the nature of billboard advertising as a medium that is necessarily for everyone.

As I mansplained on LinkedIn, the key point with Burger King is that making something an ad changes what it is. I wrote about this phenomenon in my first ever post about purpose. Several years ago, a woman was buried in a Costa-branded coffin, because she loved meeting her friends there. It was an authentic and touching story that was widely reported in the press, but Costa OBVIOUSLY didn’t turn it into an ad, because turning something into an ad changes what it is. The real and true thing becomes a crass and insensitive thing, especially when it’s published without context on poster sites across the land.

But here we have to add a side-note—because, in a complex interplay of ad industry bullshit-mongering, it seems like most of this stuff ISN’T published across the land in any case. As far as I can see, the Burger King campaign hasn’t appeared in public at all, let alone across the nation. The only images I’ve seen are mock-ups, and the campaign was limited to a single day on 26 September, when the highest number of births apparently take place. So the lack of public reaction is probably because no one knows about it, beyond the marketers arguing about what the public thinks on LinkedIn.

Meanwhile, other advertisers cheerfully use giant billboards to exchange family in-jokes in which two brothers (founders of Surreal cereal and Days non-alcoholic beer) compete for the approval of their multi-millionaire father and funder. I covered that in an earlier post, but it’s worth revisiting in light of the Guardian’s reporting that four in five billboard ads in England and Wales are in poorer areas. That was certainly the case here, where the triple poster site was in the borough of Hackney, where 43.4% of children are estimated to live in poverty after housing costs. For good measure, the site is over the road from BSix Sixth Form college, where the students are among the poorest in the country. David Ogilvy’s plan to tear down billboards in the dead of night could do worse than start here.

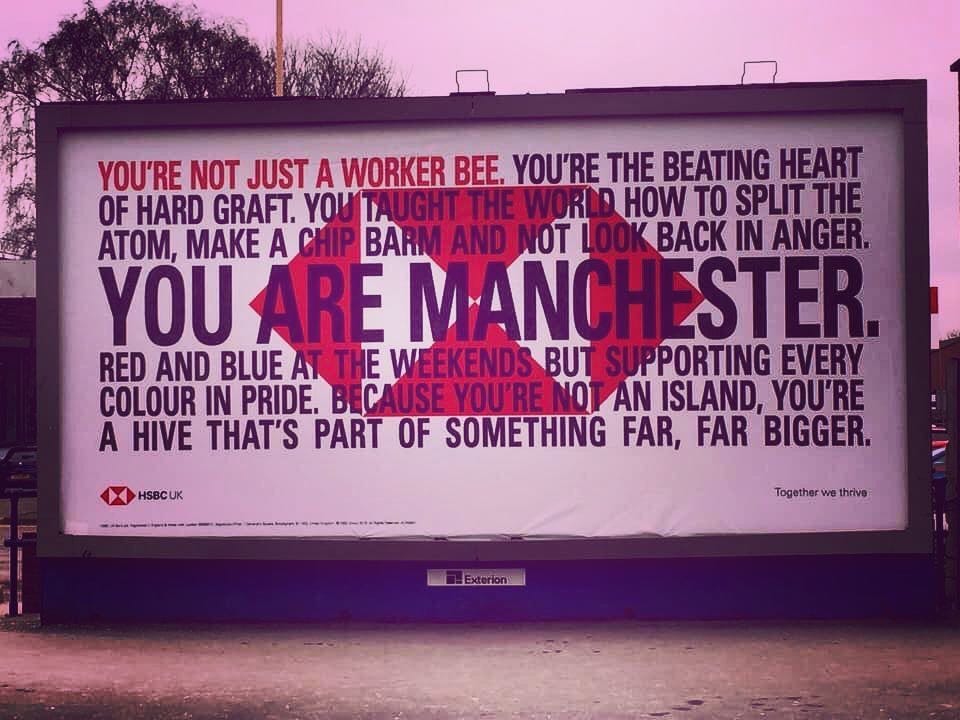

There are too many other billboard provocations to mention, like HSBC beaming into cities to patronise them with their most familiar clichés.

Or this site in Elephant & Castle, where a once-ad-free office block (image 1) is taken over by giant hoardings (image 2), to vain protests from campaigners (image 3), before Corona takes the purposeful applause for running an ad that allows some light in (image 4), albeit by funding the site’s owners and continuing to block some windows with the ostentatious frame.

Am I arguing that all billboards should be torn down? No—I think there’s a place for public advertising, and it can add light and colour to public spaces, even defining the character of places like Piccadilly Circus and Times Square.

But forget my position. Assuming the position of the ad industry is that it would like to keep using these canvases, it urgently needs to recognise the responsibility that comes with the privilege. Make it good, make it for everyone, recognise it’s a medium distinct from websites, newspaper spreads and TV ad breaks. It’s not just a photo shoot for your LinkedIn post—it’s an intrusion into the public realm that we all share.

In a spirit of moral presentism, we often like to feel superior to the backwards old generations who preceded us. In some ways, I’d like to think we are. But on the issue of billboard advertising, it’s hard to think that the purposeful industry folk of today are more enlightened than those who came before them. Agencies need to remember the social contract that enabled these intrusions—or a lot more giant, dark rectangles will soon be appearing.

Thanks for reading. For anyone new here, I’m the author of The Road to Hell, which is out in print and on Kindle. I’m also a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, books about design, and occasional songs.

Given the disparity between the types of billboard ads I see in real life, and the ones that fill my LinkedIn feed, if creativity is a legitimate justification for billboards, then we can surely just have billboards exist solely as digital mockups, a repurposed relic like the floppy disc save icon.

Of course, that isn’t the reason, and a do wish advertising would have an honest conversation with itself about the relationship between creativity and effectiveness when it comes to these.

And yet… as you point out, billboard ads have to be for everyone (in that area). No microtargeting using your data, giving just the messages about the brand/product that they think you specifically want to hear. One message for everyone. Which forces a certain honesty, or at least some sort of accountability. GenAI is raising the prospect of individualised ads where every one is hyper-personalised. No regulator could keep track of that, so accountability and responsibility become optional.