Purpose wins. Who loses?

The dominance of purpose-based work at creative awards schemes is part of an industry trend spanning two decades. But has the industry lost contact with reality?

NB: This is a long read, in five parts. Not all of the newsletters will be as long as this. Hello by the way.

Part 1: Cannes and D&AD

Another advertising awards season comes to a close and Purpose is master of all it surveys.

Cannes 2021 will put the spotlight on purpose, said the PR Week headline on the eve of the festival. Purpose takes the spotlight at Cannes, said the Campaign headline a week later. A series of reflections from jurors includes this upbeat assessment:

“As we step out of our very first virtual Cannes Lions week, there has been one thought that has overwhelmed me over and over again – how truly creative and inspiring our industry really is, especially in the face of adversity. Across all categories and disciplines, this year has shown the true impact our industry has on the world.”

A few months earlier came the Ipsos Mori Veracity Index, in which UK adults are asked how much trust they place in various professions. At the bottom of the table – below bankers, private landlords, estate agents, journalists and politicians – are the advertising executives.

A degree of grandiosity is to be expected at Cannes, but the disconnect between the industry’s self-image and the view from outside is striking. Things reached a grimly surreal nadir in 2016, when Cannes celebrated a fake app for locating capsized migrant boats, on the shores of the same sea where hundreds lost their lives that year.

What about D&AD, whose Black Pencils are billed as the ‘ultimate creative accolade’? This year, the top awards went to Boards of Change, True Name and WombStories – three projects with an explicit social purpose.

In response to murmurings on Twitter, D&AD Chairman Tim Lindsay was adamant that this is not the result of D&AD actively favouring social purpose in its judging process:

“Juries are made up of highly experienced, multi-awarded practitioners and they decide what they want to award, not D&AD. We don’t have quotas and we don’t give guidelines other than ‘great idea, beautifully executed’.”

Later in the same thread, he continues “…essentially juries want to encourage ethical behaviour and sustainable growth. As well as award straightforwardly great stuff.”

Having been involved in the judging in other years, I know it’s true that judges aren’t given an explicit steer to favour purpose-driven work. In my experience, they don’t have to be, because this thinking is now baked into the culture. D&AD President Naresh Ramchandani expresses this position in the accompanying press release: “For me, creative excellence is work that acts both for the brief and for the world, putting social purpose at the heart of commercial success.”

Many people agree, especially among the higher echelons of the agency and corporate world. The idea that doing good is good business has become a truism, continually reinforced by the awards themselves, which boost reputations and careers on both client and agency side.

As usual, there are debates to be had about how effectively these projects deliver against their social purpose. Ethicists could weigh the laudable aim of True Name against the risk of laundering the reputation of a company facing a £14bn class action lawsuit. Such questions about real-world context and consequences lie beyond the powers of jurors, who can only judge based on a single case study video. The result is to award intentions more than outcomes – and it is difficult for any juror to question the creative merits without sounding like they are against the stated purpose.

There are thornier debates around whose idea of social purpose is being elevated. The corporate world is often convinced of its moral rectitude on issues that turn out to be more complicated. Take the Prop 16 vote on reinstating affirmative action in California, where every corporation from Facebook to Twitter lined up to back reinstatement. The broadly left-leaning public disagreed by an increased majority that cut across ethnic divides. It’s not necessary to take a position on the complex issue of affirmative action in order to note the gulf between public opinion and corporate groupthink.

Returning to the awards, what is less debatable is that something more than creativity is being awarded here. D&AD may not actively encourage judges to take social purpose into account, but should it go further and actively discourage it? If jurors are marking up some projects for their social purpose, are they marking others down? How should we judge a poster for the Conservative Party, a recruitment campaign for police officers, or a cover design for the next JK Rowling book? Either way, should D&AD refund entry money for people who thought it was about pure creativity?

Part 2: The wider culture

But these are narrow points about awards schemes. I want to zoom out and talk about where all this leaves advertising and branding in the wider culture.

Growing up in the eighties and nineties, I remember a time when people laughed at ads. Now they laugh at ad agencies.

Look at the widely shared Saturday Night Live Pitch Meeting sketch that pokes fun at agencies and their clients co-opting social causes. This is Saturday Night Live – a mainstream show. There’s an assumption that everyone will get the reference – it’s no longer an inside joke.

Or look at Inside, the recent Netflix special by Bo Burnham, where he perfectly sends up the social purpose brand consultant:

“During this incredibly necessary and overdue social reckoning that we’re having in our culture, it is no longer acceptable for brands to stay out of the conversation. Consumers want to know – are you willing to use your brand awareness to effect positive social change? Which will create more brand awareness…

The question isn’t ‘What are you selling?’ or ‘What service are you providing?’ – the question is ‘What do you stand for? Who are you, Bagel Bites?’”

Outside the alternative reality that we have built from case study videos, the world is noticing this stuff. I doubt advertising executives would have rated much more highly in the Veracity Index back in the eighties or nineties, but they might at least have won some grudging respect for entertaining us. Now, not so much. From being pesky door-to-door sales people, advertisers have become the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Part 3: The Brand Purpose Fallback Position

But there’s a counter-argument to all this. Yes sure, people mock the excesses of brand purpose, especially coming from big corporations. But how can you object to elevating projects that address trans rights, female empowerment and voter registration in black communities? That has to be a good thing, right? Shouldn’t we encourage businesses to do this stuff, whatever it takes?

That is the moral shield that brand purpose builds around itself, and it is hard to penetrate with subtle arguments that this movement may harm the causes it embraces. Along with many others, I’ve written article after article against brand purpose, but the response has generally been for people to double down. It’s not that brand purpose is wrong, they say – it’s that people need to do it properly. It needs to be a business purpose that runs throughout the whole organisation.

This argument – let’s call it the Brand Purpose Fallback Position – is neatly summed up in this recent Fast Company article, which is written with admirable clarity and makes sense on its own terms. But, as the author notes, the argument relies on defining brand purpose almost entirely out of existence.

Brand purpose was originally sold as the new way of doing branding – start with why and everything follows from there. After daily examples of brands doing that and failing with cringe-inducing effects, we now have the fallback position – ‘Look, this only works if your business genuinely has a purpose beyond profit and actually lives by it’.

From the point of view of branding agencies and what they have to offer to the world, this is throwing in the towel.

If your approach to branding only works for a tiny subset of businesses that are ‘genuinely’ purpose-driven, then what does it have to offer the other 95%? Entrepreneurs trying to turn a profit, employ people and sell something customers want, while struggling with the messy realities of making a living? Should branding agencies work with them, or solemnly advise them that they need to rethink their entire business model before they can do the logo?

And why realign around purpose anyway? In that Fast Company article, the examples cited of businesses doing purpose wrong are North Face and BrewDog – two spectacular business success stories who continue to thrive despite bouts of adverse publicity. If they’re doing it wrong, who wants to be right?

The problem is there are countless examples of businesses doing brilliantly without anything close to a social purpose. Then there is a small group of brands, maybe one per sector, that get to position themselves as the ethical choice – and for whom it sometimes makes sense to put long-term brand protection ahead of short-term profit. Then there are the organisations that genuinely have a purpose beyond profit, for whom we have a useful term: not-for-profits. It’s interesting to ponder why they exist at all if purpose and profit go so well together. But the point is, agencies should have something to offer all these people, instead of insisting on their clients being saints before doing an ad for them.

Part 4: The long view

But now I want to zoom out further and look at the historical context in which all of this is taking place.

Think of the last two decades – what stories loom largest in the business world? There are surely two that dwarf all others. The first is the rise of the tech giants – Facebook, Amazon, Google, WeWork, Spotify, Uber. Most of these companies barely existed at the turn of the century – now they out-earn many small countries. The second is the financial earthquake of 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed, $2 trillion disappeared into the ether, and the business world sank into an existential financial and reputational crisis.

Is it a coincidence that the dominant school of thought throughout this period has been Brand Purpose? We’ve been talking about it since at least 2010 and it has never been more in the ascendant.

What can we read into this? Well, I recently came across a quote from Eric Weinstein – eccentric mathematician, cultural commentator and (most relevantly) MD of Silicon Valley investment firm Thiel Capital. It came up in another context, but immediately brought to mind brand purpose. The quote:

“The idealism of every age is the cover story for its greatest heist.”

Brand purpose is the corporate idealism of our age. It came about partly as a response to the crash – a conscious attempt to rehabilitate the shattered reputation of big business. I was there – I remember working on a project in 2008 that gave me a peek behind the scenes at one of the big management consultancies. I saw the slides, the early drafting of the arguments, the nascent idea of purpose as the new saviour.

But it didn’t come out of the blue in 2008 – it was already waiting in the wings. Brand purpose has roots in the Californian idealism of Silicon Valley – and this is where the heist needed its cover story.

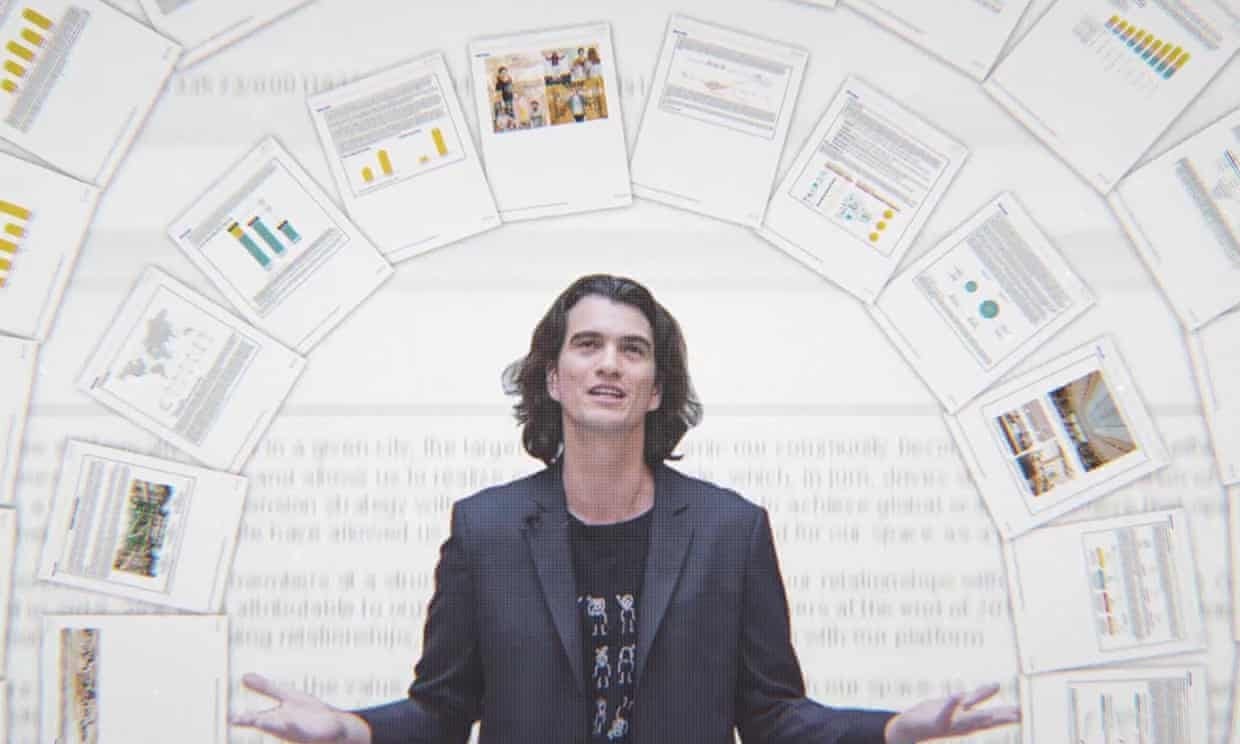

It’s a story of benign self-deception as much as outright cynicism. On some level, each individual in the chain knows brand purpose is a fiction. Facebook’s purpose has never been to ‘give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together’ – it was founded to rate the hotness of college kids and took it from there. Nor has WeWork ever been here to ‘elevate the world’s consciousness’.

But it suits everyone to pretend it is. The founders may not believe it, but they know you need this stuff to attract idealistic employees, and it boosts their personal brands at TED conferences. The supposedly idealistic employees may not believe it, but they know it sounds better when they’re talking to their friends or their next employer. The press may not believe it, but they know it’s part of the story the industry wants to tell itself. The investors may not buy it, but they know other people will, and that’s all that counts.

And so on. It’s a hazy fiction that allows people to think well of themselves, even as their decisions are driven by commercial incentives. The defining dynamic of Silicon Valley is this outward belief in brand purpose, allied to an inward focus on venture capital and IPO, where you just have to get enough people to believe in your story for enough of the time. IPO is the cashing out of brand purpose.

Mark Zuckerberg is the supreme example – brand purpose is the wind beneath his hydrofoil board. But we all live in Zuckerberg’s world. I believe passionately that, each time we lend credibility to brand purpose as a concept, another corporate sociopath gets their wings. It’s time to stop feeding this narrative that has dominated the last decade. Turn off the dry ice machine that provides the corporate atmospherics. See the world as it is.

Part 5: The recovery

This matters even more because there’s a third story that has dominated the corporate world in recent years: a global pandemic.

We’ve hardly begun the process of recovery, but it’s going to take a lot more hard-working creativity and a lot fewer soft-focus case study videos.

For business, it means rediscovering a basic and heartening truth: that businesses are pretty useful things in themselves. Recognising the positive contribution that businesses make to society need not involve believing things that aren’t true, or convincing yourself that an altruistic purpose drives all your decisions. Instead, it can be grounded in an honest realisation that, by turning a profit, you have the opportunity to employ people and pay them generously, with all the positive ripple effects that has on families and communities. You can give to charities, treat your suppliers well, and do the single most socially purposeful thing any business can do: pay your taxes.

For agencies, it means busting out of the self-heroising bubble and getting back into contact with reality. Ethnic and gender diversity is necessary but not sufficient to make that happen. We need to get people of all class backgrounds into creative departments; support agencies outside London; challenge the culture of long hours; welcome older people, career-switchers and the neurodiverse; celebrate ads and branding that are populist, popular and help businesses turn a profit; call the bluff of the tech companies promising micro-targeting utopia; remind the world of the power of mass-media brand building.

In all this, there is only one organisation that needs to rediscover its purpose – D&AD. Now would be a great time for it to stand loudly for creativity, craft, ideas and nothing else. Let others run social purpose awards, ideally using a purpose-built judging system that allows for rigorous questioning and examination of the wider context. Focus on the commercial creativity that agencies still excel at and which largely funds the purpose shop window. Most of all, stop trying to elide creative excellence with social purpose – they are different things and you do a disservice to both when you ignore the distinction.

The bright side in all this is that most people in most agencies and businesses are decent, well-intentioned and keen to do good in the world, or at least not do harm. That is the laudable instinct that has kept brand purpose going, but for years it has been channelled into the wrong conceptual framework – one that leads to growing cynicism inside the industry and growing mockery from outside it. Creativity, craft and ideas – focus on those and everyone wins.

(Thank you for reading my newsletter. As I say, they won’t all be as long as this. Please feel free to share it.)

Amen, sir. Happy to read longer posts when they are on point like this one.

This great, thank you for writing it.

“The idealism of every age is the cover story for its greatest heist.” Yes, just read the recent David Runiciman review on Thiel, the man's made a fortune grifting off tax payers $ by selling unproven tech to credulous bureaucrats!

There is something still unsaid. Why purpose?

It's a response to systemic problems caused by finance capital, e.g. cheap labor, even Fairphone can't make a phone without some child labor. They claim their first corporate act was to bribe a govt. minister to get access to a mineral mine. Forced labor is prevalent in cotton production. The CEO of FakikFashion a huge garment employer said passing on just a 2cents prince increase per garment would equate to an 8% pay rise for his workers, none of his clients, the usual brand names, would pay it. Of course "pay your taxes" but it's also a specific and necessary response to, "how are profits being made"? And the corporates are paying their taxes, that's one of the problems, purpose b.s. over here and lobbying over there in direct contradiction. The top 5 coops in UK pay more tax than the big 5 tech co's.

It's also a way to being 'politics' into the workplace without saying politics, we've been working under Milton Freidman's dictat since 1980, a right-wing position normalized into 'common sense'. It's worth re-reading the original essay because that itself was also a response, to CSR.

In his "the sole job of business is to make profit" Friedman’s assertion is that a corporate manager who speaks of the social responsibility of a firm is either stealing from someone or lying to everyone.

"To submit resources of the organization to social causes, a corporate manager must draw them from somewhere. And there are only three possible sources, none of which willingly chose to contribute to the cause: (1) the workers who must devote extra, unpaid labor for the cause; (2) the customers who must pay more for the product; or (3) the stockholders who must forgo potential profit."

Friedman admits to one additional possibility, namely, that the manager is, "actually striving to acquire a good reputation for his organization in order to increase its profits in the long run. In that case there is no specific economic sense to his moral flaw; he is simply lying: he is speaking about social responsibility whereas his real goal is profit."

Which is what you're pointing at, hypocrisy, piety and cant.

Let's say we're moving into an era where the reality behind the brand matters more than the aspirational facade it presents. Or, is it the reality behind the brand is captured by ESG, that consumers are also employees, they experience the inequities themselves e.g. exec share buyback schemes vs their wages, and so brands cleaning up their operational act *is* part of their "service" and does reflect an aspiration of their customers.

But we seem to be stuck in am opposition, "...for whom it sometimes makes sense to put long-term brand protection ahead of short-term profit." Why are those mutually exclusive? That sounds like leaving the door ajar for the practices that "purpose" is a response to, often evoked with the "being pragmatic" smokescreen.

Anyway, rambled on too long, the point is, there are significant problems in production and also in the desire factory. Freidman was the idealist of his generation, too... and purpose is only a partial paper over the cracks response, so what's the next move? Of course, there's always going to be money and markets, but there's more to this than a return to craft and ideas, there's a psychological bias in advertising towards middle-class material aspiration, the people who work in it are deeply affected, I think, so it produces a type of cultural output, perhaps there's something in that Ray William's phrase, "culture is ordinary", brands need to get off their high horses whether it's high finance or moralizing, just be ordinary, reliable, trustworthy, and good.