Fast writers and generous readers

On the risks and rewards of writing at speed, the rush to social media judgment, and why generous reading is better than sensitivity reading.

For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, downbeat diaries, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues.

Note: All this was written before the attack on Salman Rushdie

Five years ago today, I wrote a topical poem on the Notes app of my iPhone and posted it to Instagram, with a vague plan that I might keep doing it for a while.

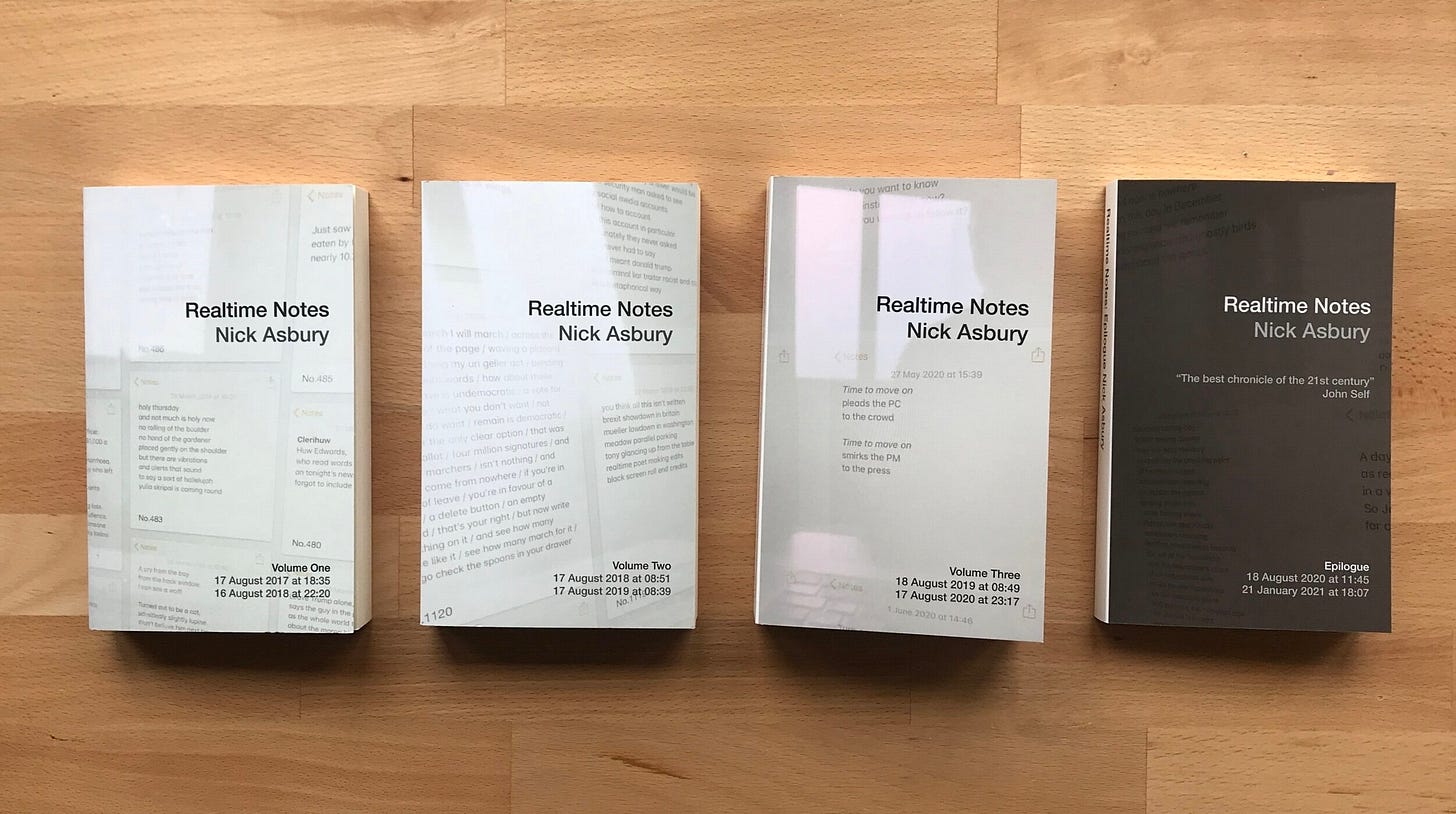

A year and a half ago, I finished my 2,113th and final poem, having posted at least one a day for three and a half years, with no time off for Christmas, Covid or Trump/Brexit Derangement Syndrome.

In this post I want to talk a bit about that experience, plus a related project of mine called Text Radio (live written interviews inside public Google docs).

But more generally, I want to talk about writing at speed—a distinctive feature of modern life, whether in Slack channels, Twitter threads or experimental poetry projects. And I want to talk about the necessary flipside: reading at speed, which we all do—you’re probably doing it right now. Sometimes this leads to writing at speed about what we’ve just read at speed, and this spirals into another distinctive feature of modern life: rushing to judgment.

I like to think I can write with some authority on this, having explored ‘fast’ writing in a few projects, and spent a career writing to deadlines. But before anyone gets the impression that I hammer everything out in real time, I should say that these Substack posts are among the slowest things I’ve ever written—I find them hard work, but sufficiently interesting to keep going. I hope you’re all massively grateful.

1. End rhymes for end times

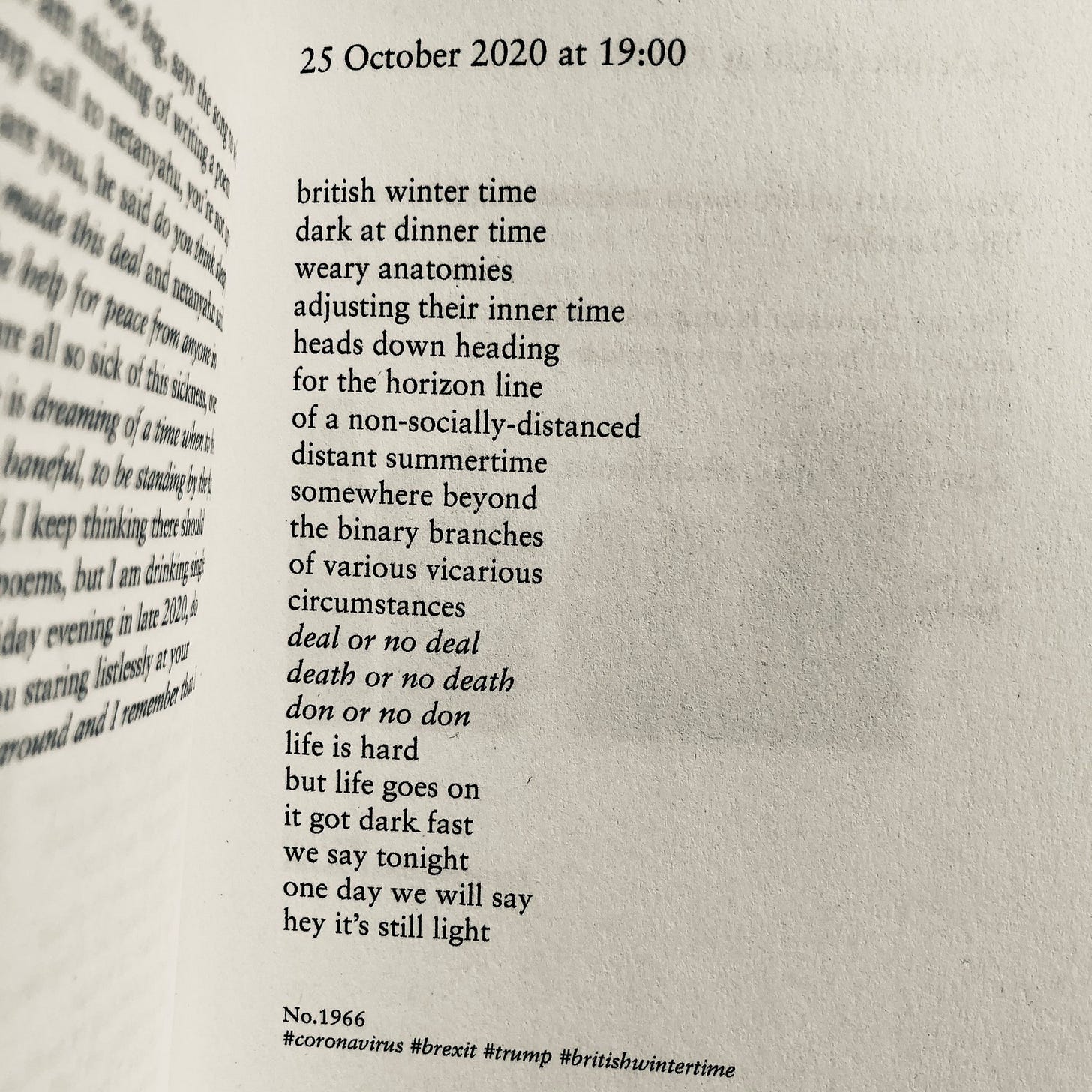

So it’s hard to pick out one poem to sum up Realtime Notes, but this one is roughly representative: lots of rhyme and wordplay; rooted in a specific, humdrum moment in time (evening of the day the clocks went back); references to three big plot lines (Brexit negotiations, US elections and a Covid winter); general philosophical theme of time, destiny and determinism; melancholic tone with a hopeful note at the end (as the time frame zooms out to include the future).

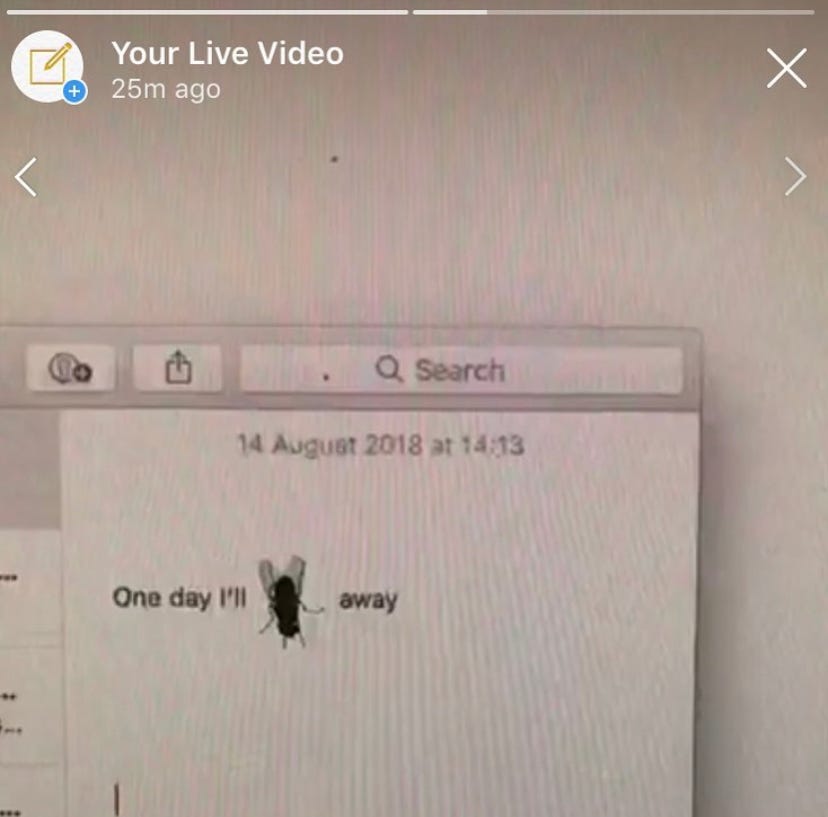

I make both no claims and grand claims for it as poetry—it’s probably frowned upon to write ‘life is hard but life goes on’ in a poem. But as a fragment from an epic work that spanned sporting limericks, instant celebrity obituaries, surreal prose poems, intricate anagram poems, visual and video poems, and a live collaborative poem with a fly that landed on my laptop screen…

…I consider it my main contribution to the world of literature, which John Self (the best critic) called ‘The best chronicle of our age’.

The key theme in the whole project was time: treating it as a formal constraint that shaped how the poems were written and read. I see time as one of the last relatively unchallenged constraints in poetry. People long ago became comfortable with poems not rhyming, scanning, or even having line breaks. You don’t even have to write them yourself—the ‘found’ poem is an accepted form. But an enduring assumption is that poetry should take extended time, both to write and read. Poetry is meant to slow you down, or take you outside of time.

It’s interesting to see what happens when you speed it up. What you lose in craft, you gain in a certain crackle of urgency. And that crackle contains a degree of risk: writing at speed about current events could theoretically get you into trouble.

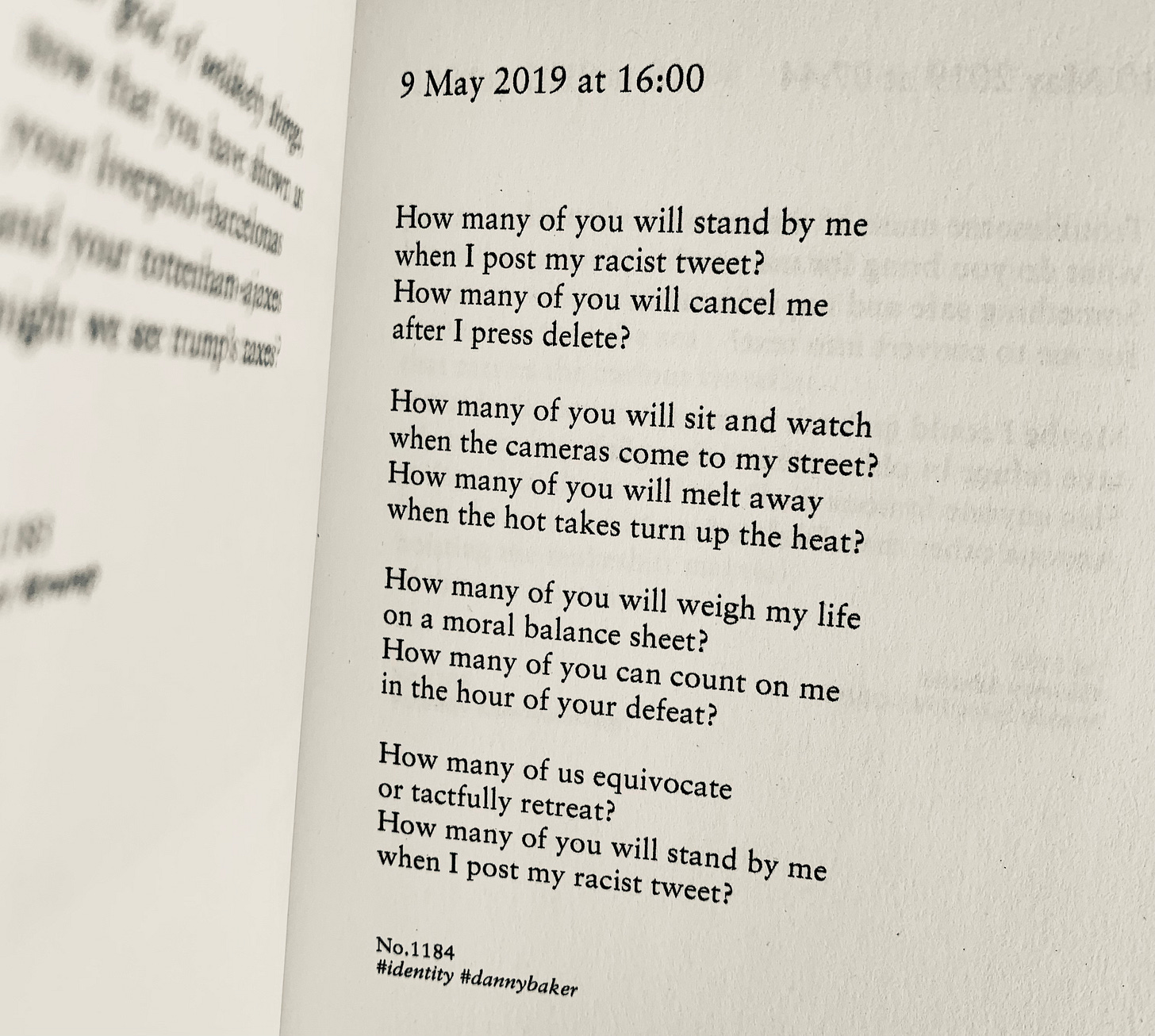

Annoyingly for my marketability, cancellation never quite happened. (I’m being ironic: I consider it an achievement to have written with some honesty about not-entirely-unproblematic things without alienating readers, at least in any way of which I’m aware. And I was on the safe side of most cancellation divides in any case—anti-Brexit, anti-Trump etc.) But I want to mention one poem as an example of potentially cancellable material, as it plays into wider themes about social media and moral judgment.

Please note this next section is not actually about Danny Baker, and I’m trying to write it in a way that is agnostic to whatever views you hold, or may have once briefly but intensely held, about that particular episode. It’s about what we think about when we think about any number of stories like this one.

2. When the hot takes turn up the heat

You may remember the incident that sparked this, and the 100% understandable outcry when prolific writer and broadcaster Danny Baker tweeted about the upcoming birth of Harry and Meghan’s first child, with a vintage picture that involved a monkey in a suit and bowler hat, framed by an Edwardian mother and father figure.

Once you saw the obvious implication, given the coded media speculation about the likely skin tone of the child, the tweet was indefensibly horrendous, and a Twitter outcry and media hounding followed.

It’s irrelevant to the wider point I’m making in this post, but nevertheless necessary to set out, that I never personally believed the intention behind Baker’s post was remotely racist, or that Danny Baker of all people (an ahead-of-his-time celebrator of infinitely inclusive cultural diversity) somehow harboured an unresolved racism that emerged like a monster when the ‘mask slipped’ in this tweet.

Instead, I saw it as a sickening example of how anyone can be caught off guard by an inexplicable brain-melt while juggling cultural signs and symbols for comic effect on Twitter. I can fully imagine the nightmarish, out-of-body sense of the ground opening up when you look at the tweet two minutes later and see the way in which it will obviously and inevitably be read.

My reading was affected by knowing a lot about Danny Baker before that one moment in time. It makes a difference to know about his long-standing penchant for stupid anthropomorphic humour, and attaching captions to fusty archive photos, and generally poking fun from a working-class perspective at the pretensions of stuck-up royals, from a position so reflexively unracist that the implication for that split second completely fell off his radar. For your part, you may entirely disagree and see this as a complacent white middle-aged gammon either brazenly or inadvertently betraying his ingrained racism—many people saw it that way at the time.

But if you delve into your neural archives, I think you can probably find something similar—some example of a cultural flashpoint where you thought ‘Well yeah, but actually no, not really’. Some case where you felt ‘There but for the grace of God’. That was the poem I was trying to write. It’s not to say anyone should ever tolerate actual racism. But the poem is a provocation: what if your thumbs tapping out your witty tweets, or your fingers rattling out your realtime poems, somehow conspire against you? What if you press ‘send’ and then your brain catches up two seconds later? What if it happens to someone you know? What if you feel an injustice is being done, but it’s too dangerous to speak up? What are your moral responsibilities in that moment, as a reader and writer?

3. The medium is the mess

One more quick example before we launch into the Moral Maze.

When writing Realtime Notes, I sometimes pictured myself as the John Motson of poetry: commentating on realtime events, and adding my own colourful spin, with fewer stats and more rhymes.

Another football commentator, Martin Tyler, recently got into trouble for a radio interview in which he mentioned the Hillsborough football stadium disaster “and other hooligan-related issues”. It was an offensive association to draw, particularly from my perspective (as a Liverpool fan, which should be irrelevant, but mainly as someone aware of the deepness of that cultural wound). But I tweeted at the time about how I felt Martin Tyler’s mistake was entirely inadvertent and easily forgivable if you make even the most minimally charitable assumptions about the person involved.

Whenever I hear about (to use the loosely generic term) ‘cancellation’ issues stemming from something somebody said, my first thought is always—where did they say it? What was the context? What was the medium? What are the chances they really meant it? In spoken, unscripted conversation, all of us are liable to say things we don’t mean—things that need clarifying, correcting or retracting. We often rely on our interlocutor to pull us up on it straight away, so we can correct ourselves in real time. Otherwise, the moment passes and we never get the chance—as unfortunately happened with Martin Tyler.

Yes, you can say Martin Tyler of all people should be used to self-editing while talking live—it’s his profession. But that’s part of the danger. If you do this a lot, you’re more likely to make at least one big mistake at some point in your career. Danny Baker is an unusually prolific broadcaster, on radio and in writing. His great strength has always been what you might call the ‘gift of the gab’—a rare and (probably) neurodivergently interesting tendency to talk and write with brilliant speed and virtuosity.

That easy articulacy might make his mistake even less forgivable if he was writing a book. Equally, if he’d made a similar remark aloud on a radio show, he might immediately have been pulled up on it and given a chance to retract. But Twitter has this simultaneous quality of being rapid and evanescent at the point of production (so easy to write and publish on your third glass of wine), while also being the digital equivalent of the tablets of Moses at the point of reception. Everything you publish is instantly fossilised for the ages. A tweet, including a deleted tweet if you’re sufficiently famous, leaves your control faster than any article or book. In the instant of posting, it becomes a decontextualised artifact, floating free from the rest of your lifetime’s output. Each tweet is mercilessly held up to the light and analysed from the most unforgiving angles, often in cases far less clear-cut than Baker’s.

I don’t pretend to be perfectly zen about any of these incidents, and each has to be judged on its own merits. For example, did Jacob Rees-Mogg really mean it when he mused aloud about how Grenfell victims should have used their “common sense” and ignored advice to stay inside? I instinctively think Yes of course he f-ing did—and there is some justification for that when you cross-reference it with all his other utterances in life. But I can just about extend some charity even to him—he subsequently made a rare apology and retraction, and apologies should mean something if we keep demanding them. I’m happy to condemn him for the utterances he does stand by and hasn’t apologised for—there are already plenty of those.

Anyway, my point for now is this: whenever you read the next headline about something terrible that someone said, the first question should always be about the medium. Was it spoken or written? Was it prepared or impromptu? Were they given a chance to correct themselves in real time? Were they in an intimidating situation, maybe speaking against the clock, or addressing a large audience? A key variable in any moral judgment should be: did they actually mean it?

The social media tendency is to read every mistake as a ‘mask slips’ moment, betraying what someone really thinks. That might sometimes be true, but could you hold yourself to that principle? Would you hold your best friend to that principle? Haven’t all of us had the experience of words betraying us in the opposite sense—by conspiring to convey something we would never remotely want to say, consciously or otherwise? That is always the danger with language—we are continually manipulating its code, and any mistakes or ambiguities are harmless 99.9% of the time. But now and again a fatal error occurs. Writers are shamed, readers are wounded, but no real human being is necessarily to blame: it’s signs and symbols messing with our heads, and it’s all happening faster than it did before social media sent us into warp speed.

4. Writing, fast and slow

The reason I write is that successful communication makes me happy and failed communication makes me anxious and depressed.

At its best, I think writing can do what speech can’t. By slowing us down, it gives us a better chance of organising our thoughts and saying what we really mean to say. Even if we sometimes fail and tweet brainless things.

But what writing loses is the sense of immediate interaction: the chance to discover your thoughts as you speak them aloud, with a real-time interlocutor to interject and take you off on tangents that end up becoming the main thread. The spontaneity of speech can be a magical thing, and a pub conversation can be a more forgiving medium than writing everything down for the ages, and for the algorithms.

With all this in mind, I’ve sometimes dreamed about combining the best of both worlds: the considered, crafted, slow quality of writing and the spontaneous, interactive, fast quality of speech.

The result so far has been Text Radio: a series of live, written conversations with fellow writers and creatives. I began the project in the early stages of lockdown and had some fascinating 2-hour, and sometimes even 24-hour, conversations with brilliant people. I would love you to go and read some of them after you finish this post.

From the first episode (writer Tom Sharp) to the last (verbal identity pioneer John Simmons) via Kate van der Borgh (writer and patient musical collaborator), Russell Davies (writer and planner) and Ravi Vasavan (designer and Deaf activist), you will find fourteen strangely intimate and in-depth conversations that are somehow different to anything you might get on a podcast: more structured and articulate, but also spontaneous and informal. Possibly the most perilous but rewarding episodes were with writer Tim Rich, where we went into issues around politics and free speech, in a way that is hard enough to write about in your own time, never mind frantically typing in front of an anonymous audience.

My point in mentioning Text Radio here is twofold.

Firstly, while typing out those conversations, I became intensely aware of the weird way in which language arises in the mind. When you observe yourself communicating in real time, it can be deeply mysterious to ponder where the words are coming from. We experience this more often with speech: if you really think about it, or have an out-of-body experience during a live talk, it can be disorienting to realise you have no idea how your next sentence is going to end. Somehow it just happens: you can feel like a spectator on your own performance.

Writing live happens almost equally as fast, but just that fraction more slowly, in a way that makes the out-of-body experience more tangible. Sat at your laptop, you see these characters appearing on the screen in front of you, and you observe your fingers bouncing on the keyboard slightly nearer to you, but sometimes it feels like your fingers are operating of their own free will, or of their own mechanistic determinism, depending on how you look at it.

I’m not arguing that talking and writing are so deeply mysterious that we should be absolved of moral responsibility for whatever comes out. But I am saying that language surfaces in our minds in weird ways, if we choose to step back and observe it. There is a strangeness to language in general: the way it abstracts us from reality, while bringing us closer to it.

Secondly, doing Text Radio brought home to me the importance of readers—the people hovering anonymously in the docs, behind the animal avatars that are randomly assigned to them by Google.

The avatars are an interesting piece of UI design, because they visualise something every writer thinks about when they’re writing anything for a general audience—whether it’s a book, tweet, article or ad. In all cases, you’re aware of these invisible presences, separated from you in space and (usually) time—and you feel simultaneously grateful for, and intimidated by, their presence. In writing Text Radio, I often found myself reminding readers that both the guest and I were writing fast in this unfamiliar medium, and therefore relying on readers to be generous and forgiving—whether it’s accepting the inevitable typos, or not immediately leaping to the least charitable interpretation of any point we were trying to make.

5. The endangered reader

What’s true for Text Radio is true for reading in general. Though I call myself a ‘writer’, like everyone else, I’m primarily a reader—sometimes of books, but more often of articles, tweets, emails, Slack posts, ads, packaging, menus, street signs: all the words that surround us every day. From the point of view of countless writers out there, I’m just another animal hovering in the corner of the doc.

Sometimes I wonder if we all need to be more aware of our role as readers, because we’re usually not great at it. We see the byline on an article and are primed to love or hate it. We judge an article on its headline, forgetting that most journalists don’t write the headline and the people who do are likely to over-simplify for clicks. We are drawn towards certain content based on confirmation bias and tribal loyalties. We seek out the dopamine hit of righteous outrage: the internet’s favourite emotion. We engage in cheap postmodern literary criticism to extract whatever problematic or ‘literally harmful’ meaning we are determined to find in a book, article or tweet—while extending benefit of the doubt to the people on our own side.

Media literacy is a key skill of our age: someone should offer a free course in it. More broadly, the art of reading generously is a rare skill that needs to be nurtured—it’s accidentally appropriate that Google chose all those animal avatars because each represents an endangered species.

Instead, we seem to be nurturing a culture of sensitivity reading and trigger warnings, as though writers and readers need protection from each other. It’s not that there’s no place for such things, but the current trend is already getting tangled in its internal contradictions. If we don’t trust authors to speak beyond their ‘lived experience’, why should we trust sensitivity readers to do the same (a necessary part of the job they purport to do)? Others have written at length about how the job doesn’t deliver on its own terms, represents a low-cost work-around for lazy publishers, and both relies on and reinforces the group stereotypes to which it’s supposedly so sensitive.

Of course, authors can always benefit from judiciously sourced feedback on all kinds of issues, including cultural sensitivities, but the institutionalisation of that process is highly ‘problematic’ and will be fertile ground for satirical novelists—the defining novel of our times will probably have a sensitivity reader as its central character, and may have to be self-published.

6. Further reading

Right now, I’m sensitive to the fact that anyone still reading has somehow made it past the 3,000-word mark.

Your reward is to discover that the complete Realtime Notes set (four books and over a thousand poems) is available for £10 plus p+p to celebrate the anniversary. (Bear in mind p&p can be a lot for those outside the UK.)

And the whole of Text Radio is available free—roughly 70,000 words of conversation about writing, creativity, music, politics, culture and other things.

Thanks as always for reading—I’m aware people’s mileage will vary when it comes to the particular stories mentioned. I’ll end with a poem from Realtime Notes that is about the experience of doing Text Radio. (For some reason, both this and the British Winter Time poem were written at 19:00—must be the internal poetry body clock.)

Thanks Nick Asbury, for showing that Copywriters have a heart (and a mind)!

I am indeed massively grateful :). I also enjoyed perusing the Asbury and Asbury website, and looking forward to getting my eyes on to Text Radio.