A decade of disappointments

On toxic positivity, the negative path to happiness, context-dependent optimism, and the lifecycle of a creative project.

Hello again. For anyone new here, I’m a writer of poetry, branding and advertising projects, articles for Creative Review and The Guardian, and books about design. Thoughts on Writing uses language as a way into wider cultural and political issues. Thanks for the many responses to Hmmm, Danone—if you followed the details closely, you may be interested in this update.

So a slight gear shift in this edition—I’m going to write about one of my own projects, for which I first had the idea 11 years ago. But I will write about it in a way that ranges across issues including social media, mental health, Stoicism, political messaging, Simon Sinek, the Brexit referendum, and the publishing industry. You will be the judge of whether I’ve made it sufficiently interesting to justify the prolonged navel-gazing. (Photo above by @lettemore)

1. The inspirational origin story

I joined LinkedIn in 2007, joined Facebook in 2008, joined Twitter in 2009 and had the idea for Disappointments Diary in 2010.

The idea came as a reaction to the relentlessly positive messages that dominated early social media, often in the form of motivational quotes: Everything happens for a reason! What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger! When one door closes, another one opens! Carpe diem! Proverbial phrases like these had always existed, but they were usually confined to greetings cards, airport self-help books, and conversations with your grandparents. The arrival of social media turned them into a popular form of ‘content’—and something about them spoke to the malcontent in me.

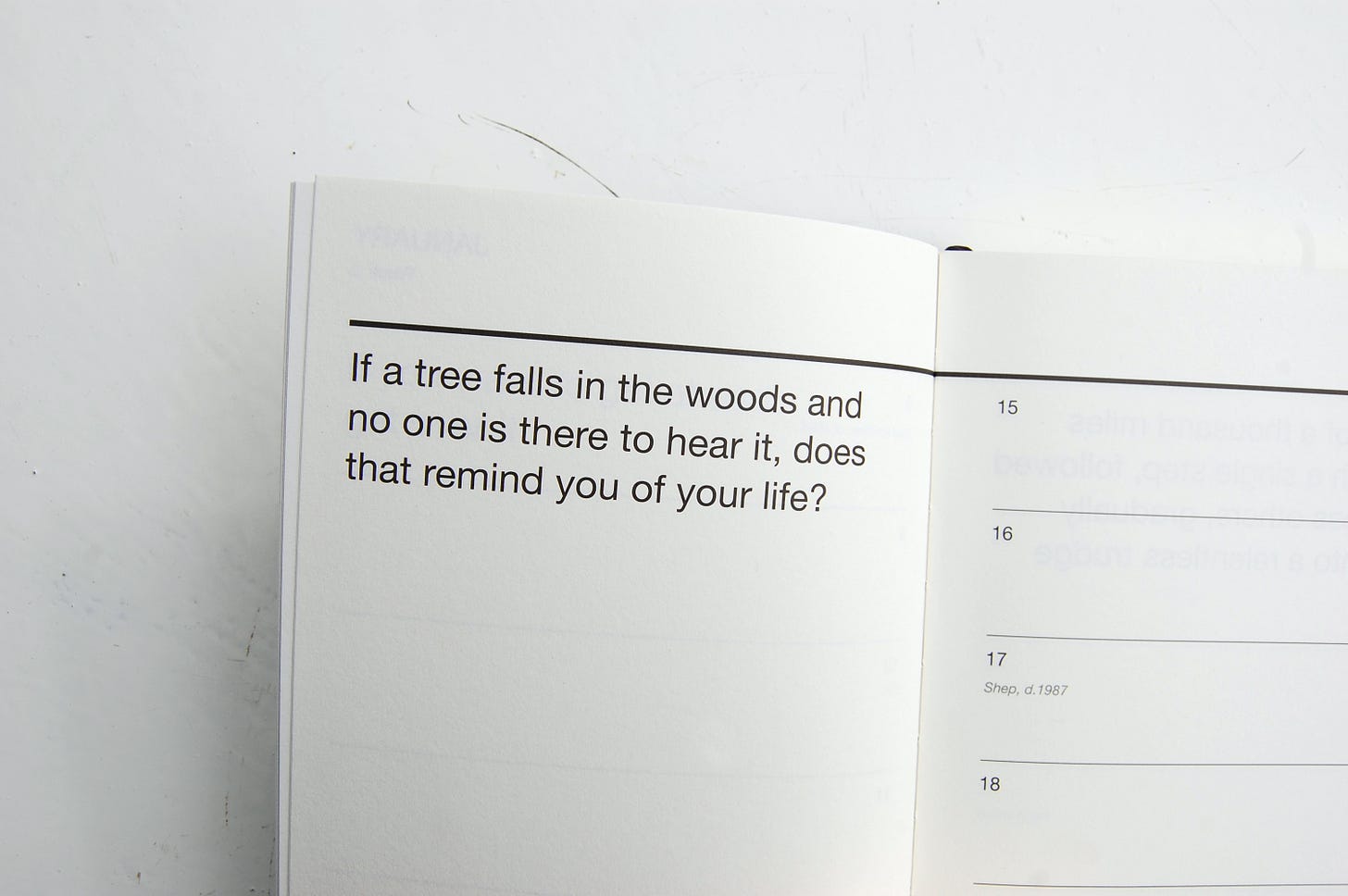

I began writing my own private ripostes, all of which felt equally valid: Everything happens for a terrifyingly random reason! What doesn’t kill you makes you wish it had! When one door closes, another one opens in your face! Crappe diem! For a while, I didn’t know what to do with them, but eventually they collided with another idea. While staring at an appointments diary one day (the kind of pocket planner where you make notes of appointments), the punster in me wondered what a ‘disappointments diary’ would look like. This was a time when mindful journaling was taking off, and I thought it would be fun to have a downbeat diary containing a demotivational proverb for each week of the year. So the idea of Disappointments Diary began to take shape.

2. Toxic positivity and emotional realism

Before continuing with this feel-good story, I should talk about toxic positivity. It’s a phenomenon that has gained traction in recent years, boiling down to the idea that continual exhortations to think positively can have negative effects. A 2018 study suggested that accepting negative emotions, rather than pushing them away, can be more beneficial for a person’s long-term mental health. According to Brett Ford, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto and co-author of the research, the expectation to feel happy can leave people experiencing a meta-emotion or an emotion about an emotion. On some level, you sense you are not as happy as you should be, so the meta-emotion you feel is disappointment.

Worse than disappointment, you might feel self-reproach or even self-loathing. The writer Caitlin Flanagan has brilliantly recounted her early experience of being diagnosed with breast cancer, and the despair she felt at not feeling as positive as everyone around her was urging her to be. She had absorbed the idea that a positive mindset gives people a better chance of beating cancer, and felt spiralling anxiety about her inability to get into the required mental zone. She reports a pivotal conversation with her clinical psychologist Anna Coscarelli:

For the first half hour in her office, we just talked about how sick I felt and how frightened I was. Then—nervously—I confessed: I wasn’t doing the work of healing myself. I wasn’t being positive.

“Why do you need to be positive?” she asked in a neutral voice.

I thought it should be obvious, but I explained: Because I didn’t want to die!

Coscarelli remained just as neutral and said, “There isn’t a single bit of evidence that having a positive attitude helps heal cancer.”

What? That couldn’t possibly be right. How did she know that?

“They study it all the time,” she said. “It’s not true.”

This isn’t an argument for being morose and fatalistic—in countless articles and podcasts, Caitlin Flanagan comes across as anything but that. But her positivity is of a different kind, rooted in emotional realism and no-bullshit acceptance. It’s the kind of positivity that comes from what is variously called the negative path or non-attachment or Stoicism—to all three of which I will return after I’ve talked more about my diary.

3. The unlimited edition

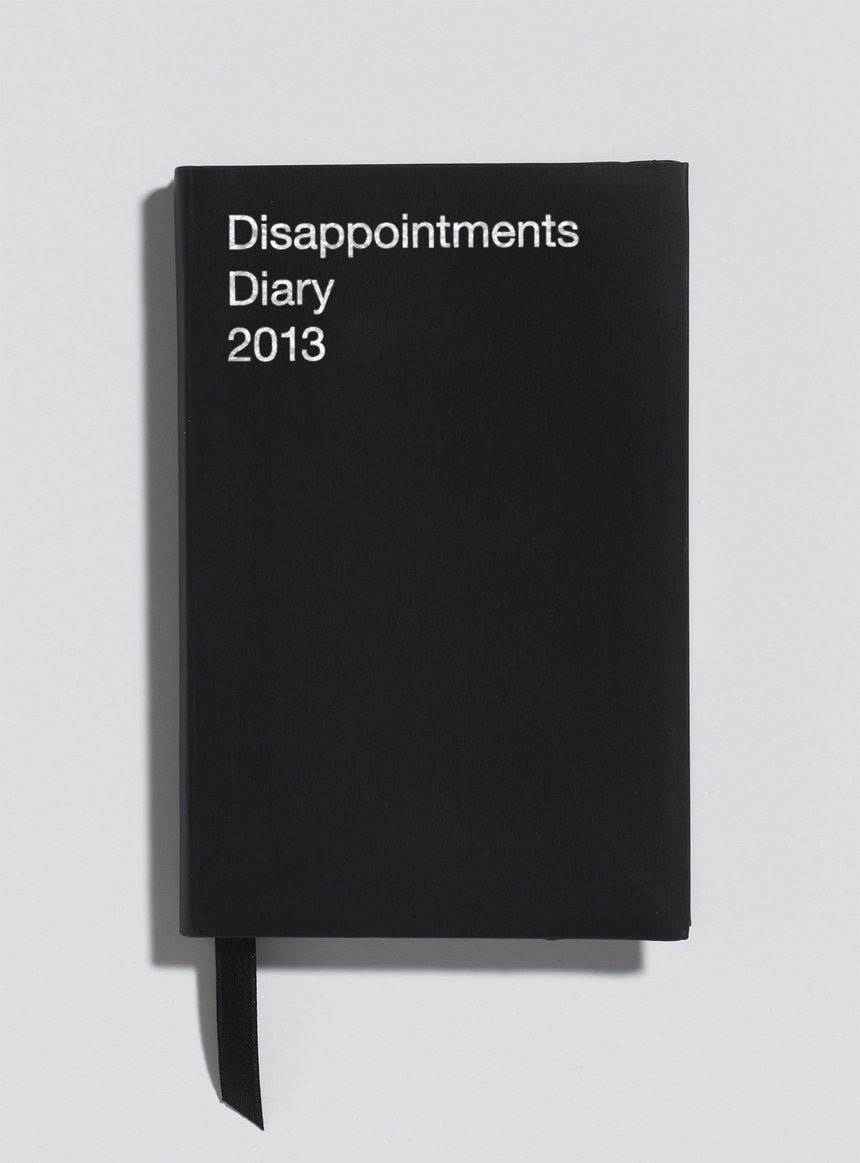

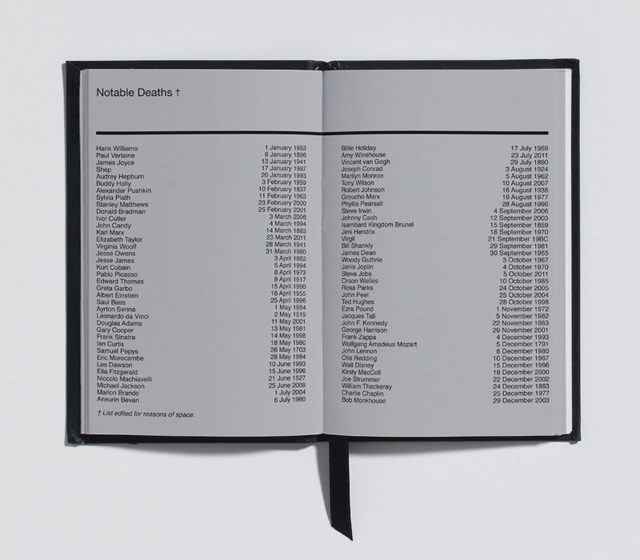

For the first edition, I bought an appointments diary from WHSmith and used it as a template: pocket-sized, week-to-view, with some informational sections at the front and back. Each week had a demotivational proverb, along with reminders of Notable Deaths (part of a Stoical tradition of memento mori that uses reminders of mortality as a way to instil perspective and meaning).

At the time, I’d started working with a designer called Jim Sutherland (then of Hat-trick Design, now of Studio Sutherland) and I asked him to help. The thing was, the words were doing most of the comedic work, with the design acting as the straight man, so there wasn’t much scope for visual fireworks. Nevertheless, Jim found room for some inspired touches, most notably the grey pages getting subtly darker as the year progressed. My wife and creative partner Sue also worked on the design and production, taking over when Jim was waylaid by 50 other projects.

Jim introduced us to a printing company in China that could produce the diary at an affordable cost—roughly £3.50 each for 1,000 copies, when a UK company would have been 3-4 times that. Spending £3,500 on a joke was a significant outlay, but I justified it as self-promotion that might lead to work—and we would hopefully cover the production costs if we sold some.

My other advantage was having enough of a relationship with Creative Review (a leading title in the UK design/advertising world) to get some coverage when it launched. The post went up and it got picked up by blogs around the world. Within two weeks, all 1,000 copies had sold. At some point in the marketing, we had referred to it as a ‘limited edition’ and each copy was carefully hand-numbered. So we did the only decent thing and printed 3,000 more.

4. The negative path to happiness

There must have been something in the air when the diary came out, because the same year saw the release of The Antidote, by Oliver Burkeman. Subtitle: Happiness for people who can’t stand positive thinking.

The book is an argument against what Burkeman calls the ‘cult of optimism’—an industrial network of life coaches, motivational speakers and LinkedIn thought leaders who espouse positive thinking as the path to success. Burkeman examines the growing body of evidence that positive thinking not only fails to deliver on its own terms, but often increases anxiety and depression. Repeating positive affirmations to yourself can make you feel worse than you would otherwise, and visualising a positive future can make you less likely to achieve it.

Instead, Burkeman advocates the ‘negative path’ to happiness, which involves embracing uncertainty and insecurity as the way to a more durable form of contentment. It’s an idea with roots in eastern and western traditions, echoing Buddhist conceptions of non-attachment and the Stoicism of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius—the latter being a keen collector of aphorisms, some of which read like wiser but less amusing Disappointments Diary entries: “The best revenge is not to be like your enemy.” “Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.” “We all love ourselves more than other people, but care more about their opinion than our own.”

You could say Marcus Aurelius was a LinkedIn thought leader of his age, but the difference is his aphorisms are memorable for their content more than their confidence. The closer you look, the clearer they get. With many LinkedIn aphorisms, the rhetorical effect is instant, but the content evaporates on closer inspection. A recent example: Those who only know what they do, work harder. Those who also know WHY they do what they do, work smarter.

That got 38,594 likes on LinkedIn—but is it true? Might some workers have an acute sense of the what and find smart ways to get it done and go home? Conversely, might an Amazon delivery driver be paralysed by having too strong a sense of her ‘why’? Does being an employee of Earth’s most customer-centric company mean she should stay and chat with the lonely old man at the door, or dash off because she has 50 other customers to be ‘centric’ about before 8pm?

The quote comes from Simon Sinek, whose book Start With Why came out in 2009. I’ll come back to it after I’ve talked more about my diary.

5. Non-Amazon adventures

The first version sold somewhere in excess of 3,000 copies. But it was also a 2013 diary and year-specific diaries don’t remain commercially viable in the way that books do.

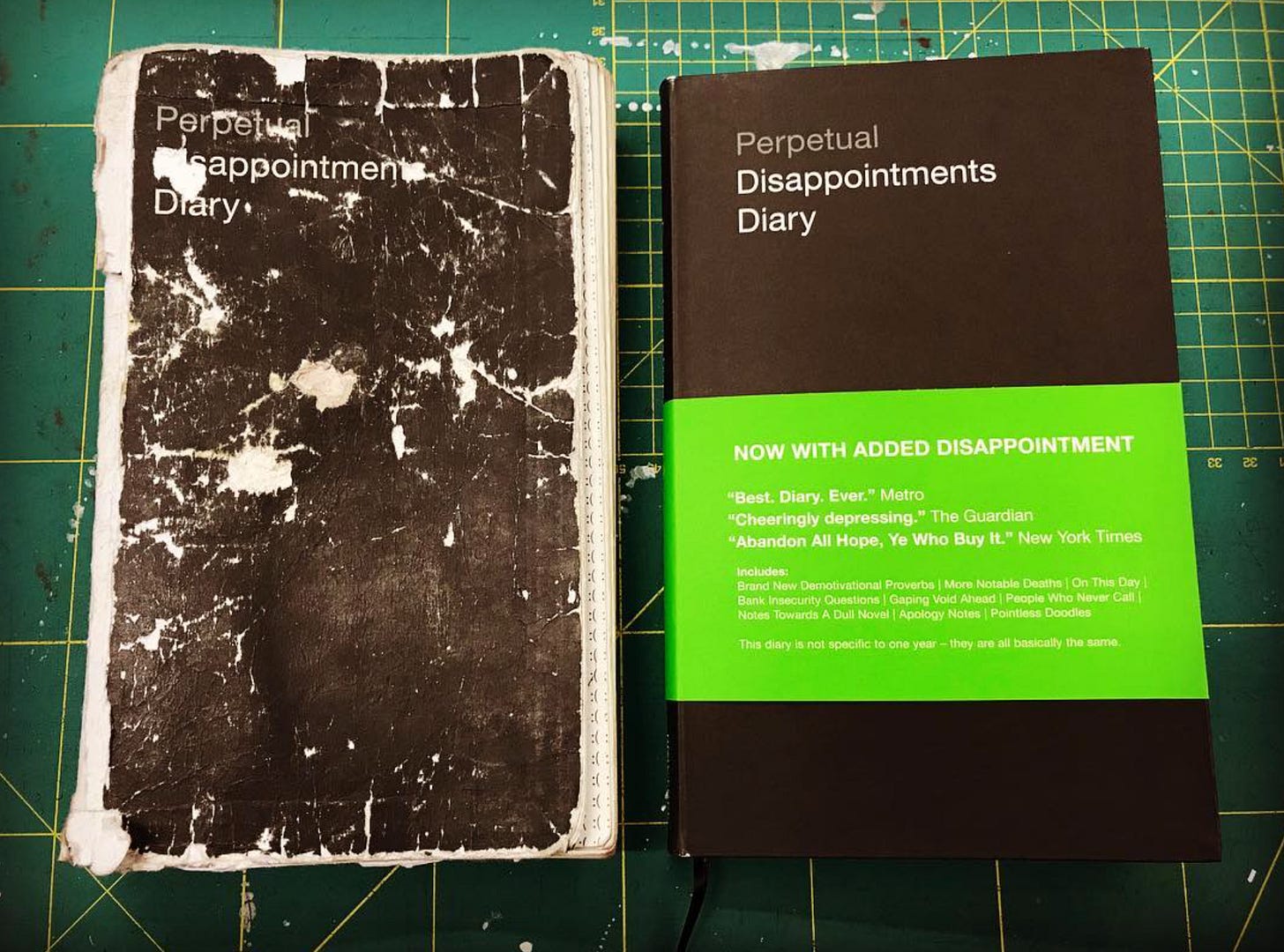

Sue and I spent some time pondering what to do next (at no point examining our ‘why’, more the ‘what’ and the ‘how’). Eventually, we arrived at two commercially-driven conclusions. First, it should be a larger format to tap into the trend for Moleskine-style journaling. Second, it should be non-year-specific (like a perpetual calendar), so we’d have a longer window in which to sell it.

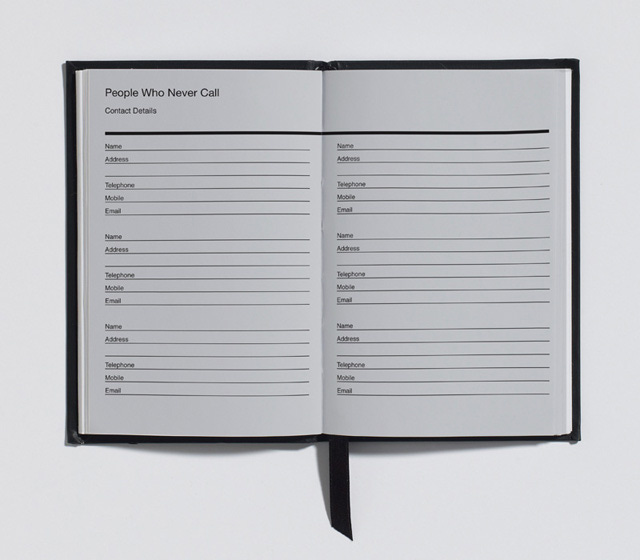

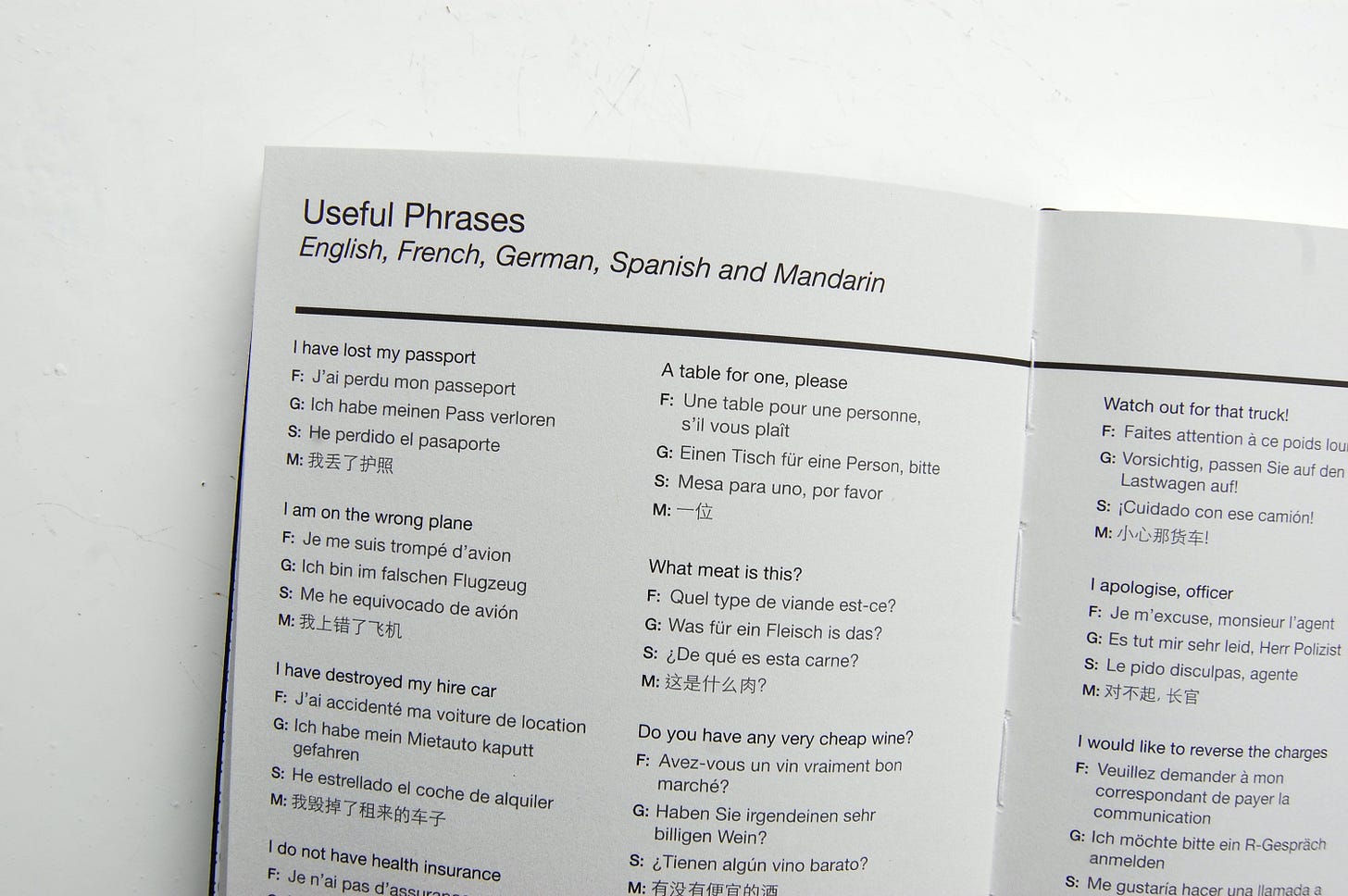

It was Sue’s idea to call it Perpetual Disappointments Diary. And the resulting journal had several new features, including greater prominence for the demotivational quotes and a popular Useful Phrases section.

When it launched in late 2014, we embarked on the most exciting and exhausting part of the story—an intense period of processing orders, queueing at the Post Office, and firing off speculative emails in the hope of press coverage. One of the emails went to the New York Times and unexpectedly hit pay dirt—I was interviewed over the phone for a Q&A feature that appeared on 31 December 2014, and our web stats went crazy for a couple of days afterwards.

The great thing about self-publishing is the visceral connection it gives you to the readers—you can see exactly who’s buying it. A funeral home in New Zealand. A LibDem MP. An executive at Everton FC. Lots of German people. There was even an order from magician David Blaine, followed by a request for 20 more copies because (his PA explained) he wanted to give it to his friends for Christmas.

Amid the excitement, continuing production problems meant we had a problem with the covers—it became evident that some were curling badly when exposed to heat or direct light. The only customer to raise this directly was David Blaine’s PA, and we were tempted to suggest David had been staring at them too intensely. But in the end we gave them a discount.

We printed two editions and managed to sell several thousand copies over a couple of years, but the stresses of production and fulfilment meant we eventually ran out of steam. Without being in shops, it was hard to maintain the momentum and visibility. I vaguely wondered about approaching proper publishers, but the whole world seemed impenetrable. At some point, I worked out you need an agent to approach the bigger publishers, and did some creative Googling to find a promising name. Having been close to dropping the project altogether, I sent out a proposal, got a reply a couple of days later, and soon find myself in a Bidding War!

6. Optimism is context-dependent

The reason I came across that Simon Sinek quote was all these posts I’ve been writing about brand purpose. The last one was shared widely on LinkedIn, where I’m not usually that active—but it turns out to be a good place for conversations that don’t go off the rails as fast as they do on Twitter.

Someone on there mentioned Simon Sinek, who turns out to be a major influencer. I’d long been aware of his Start With Why book, which did a lot to popularise the idea of brand purpose, and which I think is fundamentally mistaken. But he’s a gifted and charismatic communicator and (I discovered) remains influential in marketing circles. What caught my eye on LinkedIn was that he lists his profession as Optimist and Author.

I don’t know what it means to define yourself as an optimist, independent of context. If you plan to launch a soft drink that will outsell Coca-Cola within six months, I will be the pessimist in the room, raising objections. If you assert that it’s impossible to launch a new soft drink in this day and age, I will be the cheerful optimist pointing out reasons to be positive.

The point is, optimism is context-dependent. But when it comes to building a personal brand, calling yourself an optimist can be seductive. On a purely linguistic level, it associates you with the best, the optimal. It casts you as a happy person, a can-do person, rather than the can’t-do person who frowns as you explain your Coca-Cola-beating sales strategy. We’re conditioned to seeing frowns as grumpy and smiles as positive, regardless of the context.

And here’s where we might apply some Foucault-style critical theory:

The setting of the context is all about power.

Whoever has the power to frame the issue can decide the direction of the ‘yes’ and the ‘no’.

This was a significant issue in the run-up to the EU referendum. Research suggested that phrasing the question in such a way that the remain option meant answering ‘No’ (V3) led to a two-percentage-point decrease compared to rephrasing the same question so that you had to answer ‘Yes’ (V1). It seems people don’t like saying ‘no’ because it makes them appear disagreeable. (The government eventually went with the more neutral V2 version and everything went just fine after that.)

I make this point because I’m increasingly of the mind that positivity is a power play—a form of control that is used to suppress dissent and pre-emptively cast alternative views as negative. And one of its greatest exponents is the cheerful optimist who won the Brexit vote and is now Prime Minister.

7. Distributed disappointment

The bidding war was more of a bidding skirmish.

But it was still exciting. I sent the proposal to an agency called Bell Lomax Moreton, they forwarded it to various publishers, and before I knew it, we had a phone call offering us a five-figure advance that felt like the kind of thing you might win on a decent gameshow. But they needed us to agree in the next two hours! But then another publisher came in with a higher offer! So we went back to the first publisher… and that was the end of the skirmish. In the end, we went with the lower offer from the bigger publisher, Pan Macmillan.

The great advantage of proper publishing is distribution—getting it into Waterstone’s, Sainsbury’s (pictured above), and lots of independent shops. Even better, Pan Macmillan sold the US rights to one of my favourite publishers—Chronicle Books—who produced a super-smart US edition.

The thing you quickly realise is that you haven’t joined some giant PR machine. While publishers have a few flagship titles to which they dedicate marketing budgets, the rest seems to operate more like a numbers game—take a punt on lots of titles and hope that 1 in 50 might be a surprise hit. As far as I can see, it’s still down to the authors to do the marketing, and we’d already used up most of our leads and energy. But then just being in shops is a good form of marketing, and the diary is now in its third Pan Macmillan edition, each issue adding a few more jokes.

The latest edition came out in November 2020, but this year things have gone quiet—there is no brand new version for me to plug. That said, the advantage of a perpetual diary is that you can use it any year, as long as you’re prepared for the on-brand inconvenience of each weekly spread starting on a Tuesday.

8. All authors are optimists

So that might be the end of the story—I’m not sure there will be another edition. But it has been one of the most interesting creative adventures in my life, all unfolding against the backdrop of an increasingly disappointing decade.

Positive thinking remains a key aspect of social media and political life. Boris Johnson is the optimist-in-chief: he has a way of framing opposing views as unhelpful negativity (usually coming from ‘Captain Hindsight’ as he has named Keir Starmer). But there are many other exponents on social media, where to express certain views is to be accused of being negative, or whining, or carping.

All of it strikes me as misguided and peculiarly controlling. Most arguments are better framed as right versus wrong, rather than positive versus negative, which will always be relational and context-dependent. And I have even less patience for the positivity mindset than I did 11 years ago. It’s not a great leap to suggest that the live-laugh-love Instagram style of positivity has contributed to the mental health crisis that is affecting many young people.

I prefer Burkeman’s negative path and I hope the diary is a faithful companion to anyone who travels along it. Like all creative ventures, this one relied on quixotic optimism at the outset—why would you do anything otherwise? In this case it paid off, but I have worked on other projects where the big time never arrived. If I ever launch a career as a demotivational speaker, my message will be that you have to buy a ticket to win the lottery, but be aware you will almost certainly lose.

It's kind of funny, but in the case of this post, Everything happens for a reason!

I'm in the mid of one of my most challenging moments in life, and everyone around me screams, "stay positive!!". And I feel that's it's wrong. Trying to constantly stay positive only makes it harder to cope with real life. And just when I thought about it, I stumbled upon this post (and, of course, bought the book ;) ).

And in this context, I recommend getting to know Dr. Claire Weekes. I think you'll find her books and insights interesting.

Thank you for this post.

What a brilliant antidote to all the over-effusive joyfulness and celebration on LinkedIn. It reminds me of a friend who sent out a piss-take of those round-robin Christmas newsletter sagas with entries such as January: the refuse collectors failed to turn up on the appointed day, and February: the cat was sick